Legends of Nigerian music: Fela

By Dami Ajayi

The biggest cultural tragedy of our time would be that the name Fela Anikulapo-Kuti is not known by the majority of Nigeria’s youth. Thankfully, this is not so because of Felabration—the annual celebration of Fela’s life—and the efforts from the West. The Tony Award winning play FELA!, about the afrobeat’s maestro’s life and the recent documentary movie Finding Fela directed by Alex Gibney have helped rouse interest in the man and his work. Added to these are the reissues of his popular and obscure albums. The constancy of Nigeria’s political problems means his words ring true still.

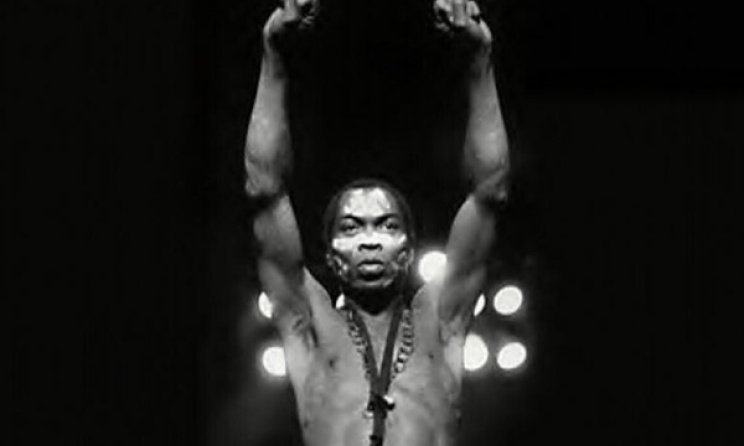

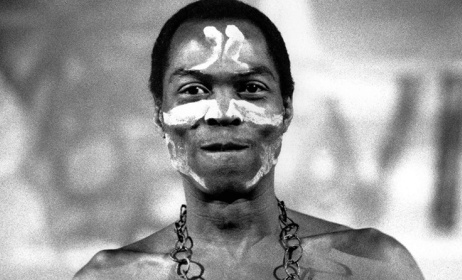

Fela

Fela

One listens to Fela’s song, Just Like That, theme song for the 2015 Felabration concerts, and wonders if almost two decades have truly passed since Fela left us. The song remains relevant. These words could have been written yesterday: “se our leader like us or them like themselves/se them good leaders or shadow criminals/se all na plan or no be plan?”

The perennial problem of bad governance is not peculiar to Nigeria; it is a Pan-African conundrum. There is evidence in the recent palace coup in Burkina Faso. One remembers Fela’s tribute song, Underground System, to his friend, Thomas Sankara, an exemplar of exceptional African leadership, assassinated just when he was on the verge of pulling the country of out its miseries.

Fela, the maverick, is gradually transmuting into a mythical figure, and even though our national conscience has refused to put out a monumental remembrance to this great son of the soil who has passed onto the great beyond, his songs continues to do what he set them to achieve. His music reminds us of our history and our past and how so intimately they relate to our present and his reach goes beyond his antics and the acerbic invective of his music. His musical ingenuity remains unparalleled and his life was a tribute to industry and focus.

How else can one describe the odyssey of Fela, who was born into the middle-class and influential family of the Kutis? His father was a protestant clergyman who formed the National Union of Teachers. His mother was also a community organiser who fought for Nigeria’s independence. Elementary school history reminds us that she is the first Nigerian woman to drive a car. Fela, known to be stubborn and rascally, loved music and it was certain that he was going to become a musician.

The journey to that becoming that which was certain took him to the Trinity School of Music where he was a trumpet major. He returned to Nigeria, a well-fed man who nurtured an afro and walked around carrying his horn. He led a band with an impossible name—Koola Lobitos—and sang about mundane things: unrequited love, heterosexual flirtations, soup. His musical arrangement, although set in the mould of the popular highlife music, aspired to American jazz with brilliant solos that kept dance floors empty.

Empty dance floors were a peculiar kind of failure for a highlife musician because highlife music is dance music. His days of playing highlife were numbered as he was chasing a bigger sound, a sound so enormous as to make you dance and ponder at the same time. He was fashioning his music to be a weapon.

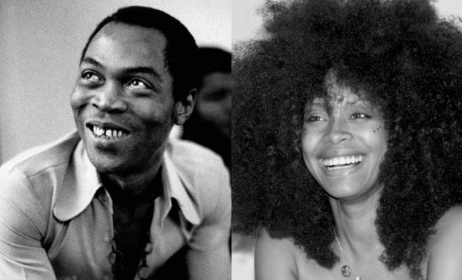

1968. America. Los Angeles was Fela’s Damascus: where his eyes would be rid of scales, his ears of plugs. A girlfriend Sandra Izsadore was instrumental in Fela finding himself in America. She helped him articulate a clear vision of Blackness, Africanness and helped him understand the direction his music should go.

The Afrobeat sound came a little later, through relentless experimentation. Fela became a music chef with an ambiguous vision. His prolificity helped. Ditto his vices: Cannabis which he had christened Nigerian National Grass; sex which he named bend-bend sleep. Afrobeat music rose from tunes of unrequited love and a kaleidoscopic voyeurism of Lagos. By the time Fela wrote Zombie, his parody tune that featured the martial music of the military, his horn had declared war on the then-ruling military class.

Of course, there were repercussions. He served time in detention and was once jailed for currency smuggling without substantial evidence. His house was invaded and looted several times; one of those occasions led to the death of his political activist mother who was thrown down from a storey building. And unbeknownst to most, it also led to the downfall of an Agidigbo musician who later enjoyed a second wave of fame at a geriatric age, Fatai Rolling Dollar. Dollar was Fela’s neighbour at his Mushin’s residence and like Fela, in the 1000 soldier raid, lost his master tapes, musical instruments and other paraphernalia.

Incorrigible especially in the face of injustice, Fela’s reprisal to the army invasion was through music. There was Kalakuta Show, a somber and caustic tune, and there was ‘Unknown Soldier’, a powerful tune where, Fela, as raconteur, narrated the pandemonium that culminated in his mother’s death. Fela always returned to the theme of the injustice of his mother’s killing, perhaps because the military did not offer him closure.

In the years following his mother’s death, there was a continual attempt to communicate with her especially through spiritual and metaphysical means. At this point, Fela, the grandson of a missionary, abandoned the Christian church for a variant of African religion for which he served as chief priest. In his search for spiritual guidance, he mingled with dubious sycophants. One of such was Professor Hindu, whom he referenced in ‘Just Like That’. It was under Hindu’s counsel that Fela refused an appetising record deal with Motown Records.

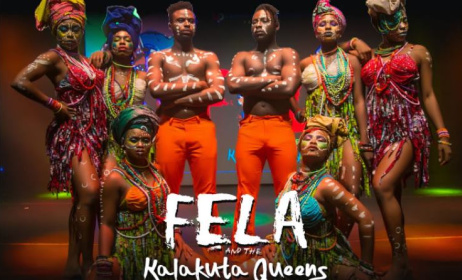

At this time, Fela had complicated his life further by marrying twenty-seven women at once at the Tafawa Balewa Square where he will lie-in-state twenty-eight years later. In Fela’s rejection of colonial presence and logic, there was an errant disregard for the phenomenon of sexually transmitted disease so that when he became physically ill and symptomatic, he insisted that he was in excellent health. When the skin lesions of Kaposi Sarcoma (a typical feature of AIDS) dotted him, he insisted that it was a gift from the gods.

His arch-enemies, the military, continued to taunt and torment him into the late nineties, closing down his self-styled night club, African Shrine, on Pepple Street, Ikeja. The Drug Enforcement Agency kept hounding the man for possessing his beloved hemp. His commune was disintegrating and his dying, the final haystack, left a gaping hole in the heart of Nigerian, nay African, masses.

Eighteen years on after Fela’s death, his Afrobeat music lives on through his biological sons, Femi and Seun Kuti, running the Positive Band and the Egyptian 80 bands respectively. His musical influence continues to thrive in the younger generation that favours digital music which Fela deeply abhorred. Afrobeat (with an s suffix) has been used to describe the contemporary digital sound popular in West Africa most notably Ghana and Nigeria.

Notable artistes like Sound Sultan, 2Face Idibia, Wizkid and Oritsefemi have revisited some Fela songs and have made contemporary classics of them. Other artistes like D’Banj and W4 have mastered Fela’s stagecraft and demeanour. Bands like Newen (based in Chile), Antibalas band (Brookyln) and Chicago Afrobeat Project have committed themselves to Fela’s Afrobeat music. Outside Afrobeat circuit, there is Red Hot Chili Peppers, Philadephia’s The Roots, Talib Kweli, Nasir Jones, all heavily influenced by Fela’s sound. And in Lagos, the land that claims ownership of Afrobeat, musical bands like Bantu, and Afrogenius embrace the culture of playing live music and serenade an audience regularly.

Fela remains one of the most unsung heroes of Pan-Africa projects. He spoke the truth to power through his music that was so sublime that message did not disrupt the funk in his sound. His life was an indignant protest against everything he stood against. Time may seem to seep away from the realities and absurdities of his existence but his discography and philosophy stand firm as evidence of one of the most original thinkers Africa ever produced.

First published October 16 by Olisa.tv

Comments

Log in or register to post comments