ACCES 2019 interview: Mark LeVine

University of California professor Mark LeVine will be speaking at ACCES 2019, where he will discuss Kenya’s Kakuma Refugee Camp and its musical treasures, namely the numerous musicians from a dozen countries who live in the camp and routinely play together, creating unheard hybrids of traditions, instruments, sounds and styles.

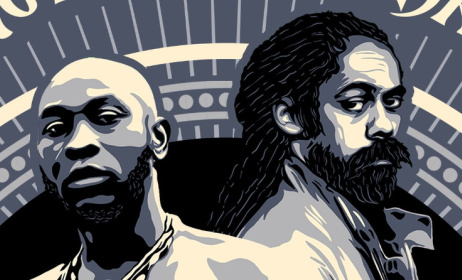

Seun Kuti and Mark LeVine. Photo: Afropop Worldwide

Seun Kuti and Mark LeVine. Photo: Afropop Worldwide

The 53-year-old historian, polyglot and author of Heavy Metal Islam: Rock, Resistance, and the Struggle for the Soul of Islam spoke to Music In Africa ahead of his trip to Accra, Ghana, where ACCES 2019 will take place from 28 to 30 November and where he will reunite with his old friend, Ghanaian highlife musician Ebo Taylor.

LUCY ILADO (MUSIC IN AFRICA): How were you introduced to African music and who were the first African musicians you listened to and liked?

MARK LEVINE: It depends on what you mean by ‘African’. I was introduced to North African music - Morocco, Algeria and Egypt especially - perhaps earliest, through the rock musicians who'd traveled there. But with Moroccan and Egyptian music, I was drawn to the music brought there by the sub-Saharan Africans who were taken there as slaves. So while I started with Arab-African music, I quickly moved to ‘black’ African music. I got into the core African artists through my love of American blues and funk.

After a few years focusing on them and working professionally, I wanted to understand the roots of blues and funk, which of course are in Africa, so I started listening more and more to them. And then I got the chance to begin travelling not just to North Africa but to the rest of Africa and started meeting and working with the artists I loved. The first was Ebo Taylor and then I got to meet Femi and then his brother Seun Kuti, and later some of the great artists in Mali and so on. Ebo for me was such an influential artist and was perhaps the funkiest artist I ever heard, along with Fela, his lifelong friend. So my work in Africa has always been about finding the funk and playing it in the motherland.

It's interesting that you mention funk, because the late 1960s and 1970s were considered to be the funkiest on the continent. The potency of this music was sweeping, from West to East.

Yes, they were the funkiest period in the history of music! My life totally changed. At the time I was playing New Orleans funk, and that's the funkiest music in America. But where did New Orleans music come from? Of course, West Africa. The ‘70s was the height of funk, and it will never be equaled anywhere. It was part of both the time of Afrofuturism and optimism, right before it all went to hell with the civil wars. Does this make sense?

Absolutely. Still, you speak of Afrofuturism and optimism in the past tense. Are we not in those times with current music such as African EDM and electronica? And are there recent artists you would single out as particularly important in carrying on the legacy of Africa’s greatest musicians, like Fela Kuti?

I'm not sure what's happening now in the electronica scene. I know it's gotten much more prominent in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently it's been big in Egypt and the Middle East. To be honest, it's not my music. I need old-school funk, I need real drums and percussion. I agree with Ade Bantu, who has had issues about calling contemporary Naija music Afrobeats. It has very little to do with actual Afrobeat or Afro-funk. But I remember talking to [ACCES 2019 speaker] Efya and also M.anifest back in 2013 when the Ghanaian sound was becoming huge. They both agreed that the way forward was to reach out and incorporate the earlier generations of the funk artists in Africa. I think Ade Bantu has done a great job with his Afropolitan Vibes project in Lagos. Also, Adekunle Gold and of course Seun and Femi Kuti. Sidiki Diabaté is another who has done straight-up contemporary hip hop but then sits with his father and plays the kora.

What about Burna Boy? He seems to have successfully managed to push Afrobeat in his music.

Well, I think he's excellent. I mean, I think his talent is far greater than the music he's generally done. Sometimes I wish these talented younger artists considered to be a core of the African sound, which is rooted in actual instruments and rhythms. But, I guess that is because I'm old now and I'm a professor, so I spend all my time at school [laughs].

The misplaced perception of worth and excellence varies and is quite evident, especially in Eastern Africa. Musicians seem to look for inspiration for musical success in other countries except their own. That's why genres like benga in Kenya and babaton in Tanzania have very few young custodians. There is an urgency to mentor young musicians, but who should facilitate this?

Mentoring is key. Look at what some of the artists in Nairobi are doing at the GoDown Arts Centre. [Afro-fusion artist] Dan Aceda and others are trying to mentor others. In Nigeria, Seun and Femi and Ade Bantu are doing their best, but pop music makes it hard, perhaps. It's much easier to learn hip hop and start making beats and recording than to take 10 or 15 years to become a great musician making music for the community.

Is today's music not for the community?

The current music scene is about getting famous and making money. It's hard to compete, and people want to monetise right away instead of taking years to learn the craft.

I believe that to be a great musician, one has to have studied music formally. How would you rate music education in Africa?

I've talked with some amazing educators in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Kenya, and they agree that there's a great education system, but I can't speak about pedagogy per se. However, there's more and more teaching of traditional music across Africa, as people realise its value.

What are your thoughts about platforms such as Afropop Worldwide and Muziki Fan, which provide research-based music information?

Well, I love Afropop Worldwide! But I work with them, so I'm biased [laughs]. I think they're so amazing. How deeply they know and love the music and how they get the mix right between academics and music. Muziki Fan is also amazing, but it's a bit more scholarly, no? I mean, Afropop Worldwide is a radio programme, so it's a bit different. But together they're amazing.

I’m interested in one project you did with Afropop Worldwide: the Hip Deep edition in Nigeria. What triggered the need to document the then state of censorship and suppression of expression in Nigeria?

It's was because Nigeria was and remains so appealing. It's not like Fela's time where you have a military dictatorship, and they would arrest, beat, imprison and torture, or even kill, people who opposed them or criticised them. Today it's more subtle.

How so?

Artists won't be arrested or attacked, but suddenly they will not get shows, ringtones, downloads, commercials, sponsorships or corporate gigs, and so on. They control them without having to use violence. In this sense, the Internet was supposed to make it easier and freer but did it? In some ways, yes, but if you want to make money off the Internet aside from selling your records, which never make that much, you have to play the political game. It happens everywhere today.

Censoring socially conscious musicians has indeed spread across the continent. But unlike in Nigeria, there are other countries like Guinea, Uganda and Cameroon where such artists are tortured and even imprisoned. In 2018, you did an interview with The Orange County Register just after you published your first book. You said that ‘the reality is that musicians don’t pose a real threat of toppling regimes, but they are a convenient target like other marginalised populations.’ Do you still believe that?

Yes. Nigeria is very different than Uganda. Thankfully someone like Bobi Wine wouldn't have the same problems in Nigeria. Cameroon is just as bad as Uganda, if not worse. When I wrote Heavy Metal Islam, I was talking about metal musicians in the Middle East and North Africa. At the time, they were very marginalised. They didn't post any threat to regimes but that was also changing, as I tried to explain in the book, and that is why I wasn't surprised that two years later when the Arab uprisings began there were musicians at the forefront. Most of the more political ones had to flee their countries or quiet down after the government's crackdown. Music is very, very important because it brings people together and amplifies messages so much.

This year, several musicians from Tanzania composed songs championing for the re-election of President John Magufuli. Is this what you mean by ‘playing the political game’?

Listen, as we both know there is a very long tradition in Africa of praise singing. There's also an equally powerful tradition of criticism through songs. We tend to have this imaginational musician somehow above us and not aligned to our narrow parochial interests, whether they're tied to tribe or religion or family or money. Still, even the greatest musicians can be venal or self-serving. For everyone who is like Fela, there's 10 who might be extremely talented but don't have his level of political commitment. Anyway, when we think about where it got him, his house got burned down and his mother thrown out of the window to her death, not to mention his wife raped, and so forth. So to be a truly committed artist is a huge sacrifice and the more successful you are, the bigger the sacrifice. Very few musicians would be willing to make that sacrifice, just like very few people in the rest of society. What I do think, though, from my own experience, is that the public understands whose music is authentic and whose music touches them. Then I think that in most cases, those artists who are too quick to praise political leaders that deserve nothing of the sort will wind up, if not losing their audience now, then losing their place in history later.

You will be at ACCES 2019 in Ghana. Will it be your first?

Yeah, this is my first one, and I'm so excited. I'm doing a session about my work in the Kakuma Refugee Camp and then I will be playing with Uncle Ebo and help present him with the Music In Africa Honorary Award. I am also hoping to get enough people interested in the book we've been trying to write since 2015. It's a book documenting the unique aspects of Ghanaian highlife, the classic sound, with all the secrets to the unique arrangements, the combination of the big-band Sinatra horns with the traditional African rhythms, the funky guitars, and the propulsive bass. We want to document that because there's no one really to carry on the tradition.

That's special. Not everyone gets to have such a moment with their favorite artist.

I mean, if you read my interviews with him for Afropop, I hope it becomes clear how important I think he is to the history of African pop music. The way he changed my life was far more complex beyond what anyone else did, including Fela.

Summarise the Kakuma project and its relevance.

I heard stories about how they were all these great musicians in the camp from over a dozen countries, and they were sitting around playing together. I knew that one day I would want to go there and meet these guys and try to hear what kind of great music they were doing. So finally earlier this year, George Ndiritu and I went, but when we got there, we found something different. We found out that there were musicians who were in the camp but had no traditional instruments. So we opted to create a project that could bring traditional instruments from Burundi, South Sudan, Sudan, Uganda, Somalia, Ethiopia and Congo to the camp. We're hoping that as the musicians get these instruments, it will strengthen their ties to their home cultures and help make the camp feel more like home. I believe that there is the potential to create a sound in the camp bringing together all of these cultures and musicians that will be very new but also be very recognisable.

Mark LeVine’s ACCES 2019 session, Harnessing the Power of an African Refugee Camp's Musical Treasures, will take place at the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences on Saturday 30 November.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments