Struggling to define a nation: A selective overview of South African jazz recordings 1959-2009

By Marc Duby

Lara Allen, writing of the origins of South African kwela music of the 1950s, divides the history of the country into three distinct periods. Following “Gramsci’s notions of the relationship between culture and society’s economic base,” she identifies three points of what he refers to as “situational change”.

Marc Duby

Marc Duby

In the South African context, these are the first period of colonialisation (1652), the second of industrialisation (1886), and the last of the installation of apartheid and the struggle for independence (1948). These dates coincide with the arrival of the Dutch voyager Jan van Riebeeck at the Cape of Good Hope, the discovery of gold in the north of the country, and the coming to power of the Nationalist government.

As Allen describes it, “Each situation brings with it a primary method of allocating social, economic and political power: colonial categorisation is racial; for industrialists power is allotted according to class, and in the struggle for majority rule the primary aim is the inversion of power in both the above categories of race and class.” Through such Gramscian lenses, categories of race and class seem both static and rigid, with the attendant dangers of essentialising and totalising a situation that was far more fluid than the grand narrative of apartheid ever admitted. Alternative viewpoints might consider how the migrant labour system and urbanisation contributed to “the fragmented and ambiguous nature of class formation in early twentieth-century South African society,” as Veit Erlmann states in African Stars, concluding from this that a concept of class as a homogeneous category is problematic as a tool for understanding South African popular music.

In Durban, for instance, black residents may have performed class-based distinctions in their performance activities, but the analysis of recorded material reveals that virtually all sectors of the city's black population drew on the same stock of musical techniques and practices.

Identifying three areas for future research (“the growing class differentiation in South African society, the development of popular music after 1945, and the growth of black resistance to political and cultural domination”), Erlmann (ibid.) concludes by highlighting “the need to situate the development and ideology of modern performance styles within a network of fluctuating group relations.”

It is important to note that Erlmann’s focus is on recordings, which are relatively rare in the context of early South African jazz and popular music. Christopher Ballantine’s pioneering study Marabi Nights (1994) provides a fascinating account of the links between early jazz and vaudeville in South Africa, as well as a number of recordings of the time and other archival material (photographs, posters, and so on). The first edition of his study included a cassette tape with rare examples of archival recordings of the 1930s and 1940s.

I want to emphasise the point that while the histories of jazz and popular music are intertwined with the history of twentieth century recording technology, this relationship should not blind us to alternative histories of live performance (ephemeral as these may be). Further, music and resistance coalesced in the form of protest songs galvanising political rallies and accompanying industrial action in the field, beyond the confines of the recording studio.

Above all we need to keep in mind that the record industry is a capitalist enterprise with the stated purpose of selling products, which are to a degree purpose-built to cater for the tastes of an imaginary public. The South African record industry often served the interests of the dominant ideology, especially under grand apartheid where the state’s apparatus of control extended to censoring lyrics and album covers that were construed as “undesirable,” a label that covered a multitude of sins from pornography to political resistance.

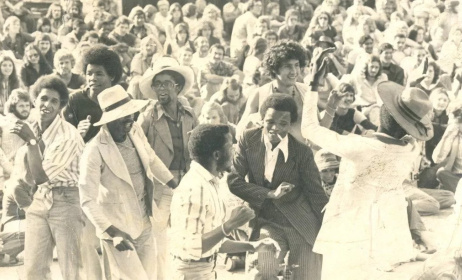

In this address I survey selected recordings drawn from fifty years of South African jazz in relation to socio-political events, discussing the circumstances under which they were produced and their impact and legacy as social texts that served to unite resistance against the status quo of the time. The recordings, arranged in a historicist framework for the sake of a coherent chronology, stand as reminders of underlying themes of journeys both physical and aural, exile and homesickness, struggle and overcoming. As such, these artifacts bear witness in sound to networks of relationships between jazz in South Africa and elsewhere in the world and local responses to jazz as practised in the United States and Europe. Through the hardships of exile, South African musicians brought “a whole dialectic of richness” to a wider international audience.

South African jazz conceals an undercurrent of dance and anger, tradition and freedom, a whole dialectic of richness, which doubtless explains the attraction that this antipodean music exerts on the revolutionary Archie Shepp. (Jazz Magazine May 1989, cited in McGregor 1995)

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments