Music education in Ivory Coast

By Jacques Thomas Le Seigneur

The text provides an overview of music education in Ivory Coast. It was in 1887 in Elima in the South-Comoé region that the first modern, Western-style school opened its doors. Music had a place on its curriculum. After a break between 1914 and 1924, a time when music was removed from the syllabus, music was restored to the programme and remains so till today. However, this arts education is largely imported from Europe, so formal music education is still struggling to take roots in Ivory Coast and is still far from playing the educational role expected of it in Ivorian society.

www.ecole-primaire-hautchemin-pace.ac-rennes.fr

www.ecole-primaire-hautchemin-pace.ac-rennes.fr

Cultural adaptation

Music education cannot be separated from the colonial and postcolonial history of Ivory Coast. It is the result of replacement of some local cultural values with those of the French occupiers. The word ‘education’, for example, in the modern European sense (take, for instance, the definition given by Emile Durkheim[i]), is close to the meaning given to the same concept in several Ivorian vernaculars. Among the Akans in central Ivory Coast (Baule) and eastern Ivory Coast (Agni), the sense of educating a child is expressed by ‘Ba Tale’, which literally means ‘plant a child’.For the Mandes in the north, the phrase close to the same concept would be ‘Denial lamon Ka’, which means ‘to ripen the child’.

What differentiates the ‘traditional’ French pedagogy from the Ivorian is probably the medium by which each is passed on: through written tradition (for the former) and oral tradition (for the latter). This difference is particularly noticeable in the arts and their transmission. The understanding that people have of music in the West does not convey the many forms it can take in Ivorian society. In French, according to the CNRTL[ii], the first definition of the word ‘music’ is a ‘harmonious and expressive combination of sounds’. In many Ivorian societies, however, the audible expression is not separated from other art forms such as dance. In several local vernaculars, one uses without distinction the same word for dance and music. For example, in Bete, song and dance are designated by the same word, ‘lô’.The same is found among the Mahous with the word ‘lon’.

The Ivorian context

Ivory Coast is at the intersection of major cultural influences that colonial history could not erase. One can divide the various communities on the Ivorian territory into four language families that correspond to the many ways of conceiving and transmitting music: the Gurs in the north and northeast of the country; Krus in the western and central part; Mande the west and northwest; and the Akan or Kwas on the central, eastern and southern lagoon regions. Note too that the national culture was enriched by influences from a very large foreign population[iii].

With a young population (in 2014, just over 77% of the national population, or 4 Ivoirians out of 5, were under 35 years[iv]), education is a priority for the Ivorian nation. However, the political will for the establishment of a strong national arts education is not shared by everyone. First, as President Felix Houphouet-Boigny liked to say, “The future belongs to science and technology” -music education is often seen as secondary where other courses are judged more ‘intellectual.’ Also, as we shall discover, the development of music education in Ivory Coast does not follow the same tempo in all educational institutions.

Music education in primary and secondary schools

Since 1977, Ivorian legislation stipulates in Article 14 that the kindergarten should develop the “artistic and physical expression” of the child[v].Music education is at this age is focused on musical initiation and vocal development. However, because of a lack of training and sometimes a lack of interest from teachers, music is often totally absent at this level. Moreover, the institutions concerned (too few altogether) affect only a marginal population; before 2001, only 8.82% of Ivorian children were enrolled and attending kindergarten schools. Therefore at this level, very few children are involved in music education.

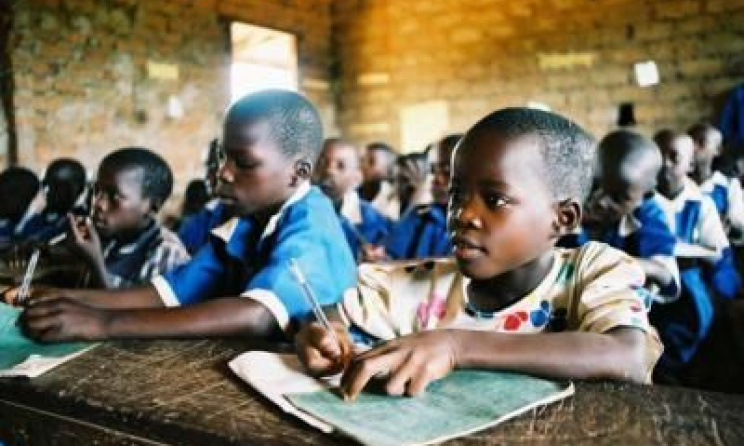

In elementary schools, music education is included on the list of lessons to be taught. Note that from 1887 to 1971, the musical practice was limited to the practice of singing in these schools, based on a French repertoire. Long after the country’s independence in 1960, one could still hear children in Ivorian schools sing traditional songs of the former colonial power, such as ‘Marseillaise’. Even after a decade of revised educational televised programmes (1971-1982), the first documents drafted on primary education, giving a place to music education, still drew from these same old texts.

In 2001, some 82% of the two million school-age children had access to primary education, and therefore to music lessons. However, with regard to nursery schools, a problem of formation and development was noticed. Even when included in school curricula, music education was often poorly taught. Teachers, receiving only limited instruction in this area, often used time allocated for music to teach other subjects that they considered more important.

The same phenomenon is seen at the secondary level too, where music is now part of the syllabus. If in 1960 music lessons were found lacking in the secondary curriculum, it reappeared in 1971 with the creation of a specialized teacher training structure: L’Institut National des Arts d’Abidjan (the National Institute of Arts in Abidjan) in collaboration with the former Ecole Nationale Supérieure (or ENS). Like the primary school programme, however, the secondary curriculum before 1982 was the same as the French model. It was divided into three areas: singing, music theory, and the history of European music.

A new, ‘Africanized’ programme has since been conceived to replace what was inherited from the colonial past. However, few instructions and prescriptions are still given to teachers. Moreover, this new programme still struggles to detach itself from the French model. One may question the relevance of having kept the teaching of music theory as one of the focal points of music education, even when music in Ivory Coast comes from an oral culture. Also, note that the study of musical cultures remains focused on the West: of 59 lessons in the programme, only 16 are on Ivorian music, compared to 28 on European music. Note that the study of the music of neighboring countries, which was culturally close to Ivory Coast’s, are not even on the programme.

Music education in secondary schools also suffers from a lack of sufficient faculty staff. For example, in 2001, for 373 492 high school students, supervised by 11 894 teachers, there were only 189 teachers of music education. In other words, of 203 Ivorian schools, only 117 secondary schools had a teacher in musical education (that’s 57.63%)[vi] - and most of these teachers did not always have the time to take care of all the classes in their schools.

Music education at tertiary education

At the level of higher education, there are three institutions providing music training in Ivory Coast: CAFOP (Centre for Educational Training), the National School of Music and Félix Houphouët-Boigny University.

The CAFOP is a group of training institutions for teachers. Founded in 1966 to meet the shortfall of teachers at the undergraduate level, music is taught alongside other art forms for all aspiring teachers but remains poorly represented in proportion.

The National School of Music in Abidjan, part of the Higher National Institute for Arts and Cultural Action (INSAAC)[vii], fosters teacher training programmes (for college and high school) and of CAFOP, and also aims at higher education up to the level ofthe French ‘Licence’and Ph.D.

At Félix Houphouët-BoignyUniversity[viii](remember that arts education only began at college level in 1986, with the Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences becoming the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Humanities), after restructuring higher training into Training and Research Unit (UFR), music became in the new Faculty of Information Communication and Arts (UFRICA) - a wholly distinct subsidiary entitled Music and Musicology, issuing a ‘Licence’ in music and musicology. Music education can be continued to a Masters and even Ph.D. level. Following the various political and military crises of the 2000s, the university was closed in 2011 by the current president, Alassane Ouattara, and rehabilitated in 2012. Despite these rehabilitation works, the university still cannot meet the demands of the population. Its infrastructure is judged to be inadequate and non-functional.

Challenges and solutions

The development of public music education in Ivory Coast, which has to meet the challenge of a dense population, faces the main obstacles of irregularity and instability coming from the political sphere that structures it. If many decisions have been taken on education, in general, and therefore on music education, in particular, this sector suffers from numerous shortcomings that the state encounters difficulties fixing.

Such shortcomings are allayed by the efforts of other institutions in Ivory Coast, which allow access to music education. First, traditional teaching remains active in families, passed on to the younger generation by elders, or by brothers, cousins, neighbours and friends. Second, some private and religious institutions allow their members to acquire some training in music. This comes through private music schools, artists offering private lessons, and also churches that purchase instruments for their worship, therefore allowing their members an entry into the world of music. Third, one must mention the many NGOs that, with the help of international funding, work on the dissemination of musical knowledge. For example, the Action Saint-Viateur Fund, supported by the Embassy of France in Abidjan and UNESCO, has created the St. Viateur Conservatory of Music and Dance that provides both practical and theoretical education[ix]. The Goethe-Institut, the German cultural centre of Abidjan, through its Music In Africa project, helps lay the foundation for a platform for the exchange of knowledge and expertise that is available to all[x].

However, it remains difficult to precisely quantify and qualify the important work done by these actors, and the majority of the Ivorian population today remains excluded from all institutions providing music education, despite the fact popular music does not seem to have stopped playing in the streets of Abidjan.

Two other informal institutions play a major role in the musical education of the Ivorian population. Zouglou and Coupe-Décalé add to the reputation of Ivory Coast, despite its lack of official institutions, as one of West Africa’s most productive countries in terms of popular music. The street, understood as an urban public space, is at the crossroads of numerous meetings, which artistically allow for communication, trade and transmission of musical knowledge. Zouglou, for example, took its roots among urban Ivorian students in the second half of the 1980s and became the fruit of encounters between several artists that until today is passed from generation to generation.

The technological upheaval of the digital age, particularly the spread of Internet, also brings new Ivorian generations to consider the creation, production and distribution of music through other means. In the 2000s, when the country was paralyzed by a deep political crisis, the production and dissemination of Coupé-Décalé continued unabated through new means of communication, exported to all countries in Francophone Africa.

These two popular music forms also express certain aspirations of the local youth, whose institutions (official or not) they build on. The musicians of the new generation, though from an urban environment, show interest in local heritage. The attempt to nationalize the school curriculum since the 1980s appears to have failed in detaching the youth from the Western model, and has largely ignored the cultural riches of the many groups that make up the nation.

Through its unifying role during periods of conflict, contemporary popular music plays a central function that is often subdued by the influence of Western culture. It shows that the construction and expression of a musical identity first allow for the construction of a strong cultural identity and that beyond the artistic knowledge that it brings, music education is primarily education through music.

[i]Education isthe action exercised by theadult generationonthosewho are notyet ripe forsocial life.It aimsto encourages anddevelop in the childa number ofphysical, intellectual and mental conditions demandedof him/her andthe political societyas a whole, for the social environmentin which he/she is particularly destined. Cf. Education: Its nature, Its role in ‘Education and Sociology, QuadrigaPUFp.51 andAlcan. p. 49.(Translated from original French). [ii] Centre National de RessourcesTextuellesetLexicales (CNRTL) is a centre that volunteers to feature linguistic lexical online.www.cnrtl.for [iii]In 1998, the National Institute of Statistics estimated the number of foreigners to be over 5million people or consisting of 30% of the national population. The 2014 general census put the foreign population at 24.2%of the national population.In 1998the National Institute of Statistics estimated the number of foreigners to over 5million people, or consisting of 30% of the national population. The 2014 general census put the foreign population at 24.2%of the national population. [iv]According to the last general census conducted by the National Institute for Statistics. [v]Law of August 16, 1977, on the reform of teaching. [vi]Going by statistics given by KOFFI Gbaklia Elvis Emmanuel in Education musicale en Côte D’Ivoire – Histoire-pratique-democratisation. [vii]www.insaac-ci.com/institut.html [viii]www.univ-fhb.edu.ci [ix]http://www.fasaintviateur.org/ [x]http://www.musicinafrica.net

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments