Chale Wote: Where art and music collide gloriously

The weeklong Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Accra, Ghana, an August spectacle for 13 years, is a vivid capture of the science of sound and the intersection of contrasts, where the power of keen glances is richly rewarded. Music, very much part of this commotion, is also a landing place.

King Ayisoba performing at Chale Wote 2023. Photo: Facebook

King Ayisoba performing at Chale Wote 2023. Photo: Facebook

This year’s edition, produced by Accra [Dot] Alt, shifted its epicentre from Jamestown District to Osu, climaxing at the iconic Black Star Square on 27 August.

Grand music concerts crown the last two days of the festival, with veterans Amandzeba, King Ayisoba and Gyedu-Blay Ambolley as headliners, and boy, did they show a gulf in class. The first two helm Day 6, while Ambolley, recently returned from a string of European performances, takes lead on the final night. These three, representing a respected class of live performers, also constitute some of Ghana’s most in-demand musical exports, their work infused with tradition, social commentary and advocacy.

When he emerges, draped in a smock, oversized slippers and a scarf that subverts his usual deity-inspired plaited hairstyle, Ayisoba looms larger than life. Even after multiple albums and international tours, the singer, who catapulted to national acclaim with 2006 hit ‘I Want To See You My Father,’ off his debut album Modern Ghanaians, stands before us just as possessed, just as fearless.

“Are you happy?” he roars. His voice elicits both goosebumps and cheers. The crowd’s resounding response clearly shows they have missed him.

Performing, in broken English, Twi and Frafra, Ayisoba’s voice carries an almost incantatory quality. Mid-way through his set, he urges the multitude (commands, really): “I want to hear everybody’.” The crowd, helpless under his spell, happily obliges. Ayisoba’s medley on the night, carried largely on his wizardry of the two-string kologo, includes ‘The Whole World’, about the tribulations one faces when starting something and records advocating for the preservation of native languages for the next generation, or confronting societal ills, vehemently condemning ‘Wicked Leaders’ and issuing a poignant caution against envy and covetousness.

Amandzeba, who takes the stage soon after, is the visage of a warrior, adorned with beads and cowries, embodying a blend of strength and culture. His performance commences with a lament for the enduring plight of Africans, juxtaposing the continent’s abundant resources with its unyielding suffering. Casting a critical eye on present African leadership’s allegiance to the West and China, he invokes the spirit of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s founding leader. His tracks like ‘Biako Ye’ and ‘Pioto’ rally for national unity and accountability, while ‘Wogbe Jeke’ serves as a history lesson, narrating the origins of modern Ghana. ‘Demara’ preaches self-focus. Before he segues into ‘Dzoo,’ an anthem propelled by resounding horns, he smiles; “highlife is beautiful!” As he bids adieu, he leaves the crowd with a reminder of ‘Kpanlogo’ from his days as a member of the supergroup Nakorex alongside fellow greats Rex Omar and Akosua Agyapong.

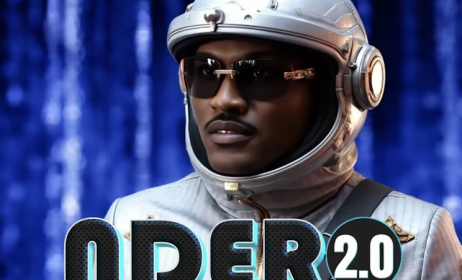

When he shows up the following night, in colourful fabric and with his signature tweed hat worn backwards, Ambolley is a professor hard at work, effectively presenting a live band master class.

A seasoned saxophonist, Ambolley’s prolonged interludes and added melodic embellishments extend live renditions for minutes on end, and his stage work takes you by the hips first, and then by the soul. His writing style combines street language and clever and comedic refrains, featuring elements like call and response, heavy percussion and horns, and English-to-Twi translation, all infused with the vocal fervour that reminds you of James Brown. His music includes discussions on family, friendship, heritage, love and hard work. This technique, tested and approved for many decades, has ensured a sustained tour calendar even in his mid-70s.

Ambolley’s stage presence is a subtle blend of action and stillness – but his charisma is felt all around, whether he’s belting out saxophone solos, conducting his band, or engaging in crowd work.

The festival thrives on paradoxes – calm is danger, the superfluous is commonplace, and everyone is subject to artistic impressions and influences.

Before the concerts, against the ocean breeze, the event transposes a symphony of urban existence to calculated chaos. For moments, you fear you are about to faint due to fatigue in your body. Cars honk, motorcycles roar, phone cameras click in selfie mode next to celebrities or at art exhibitions, ice cream carts squeak, and skateboards creak and crack under acrobatic young men. Overhead, there are occasional flying noises of drones. Yet, music remains the guiding force, threading eras, genres, and geographies. The air is thick with selections ranging from hip hop and highlife to Afrobeats and reggae, coursing through makeshift bars and various stages. Hand in hand, companions, in eye-popping fashion and painted cheeks, haggle with vendors who have accosted them. Elsewhere, chattering and muttering, they navigate the crowd, briskly or patiently.

In a corner to the left of the main stage, before the Egungun masqueraders begin their performance to usher in the final night of showcasing musicians, four young men film a music video using minimal equipment and the remaining natural light. Their protagonist, an unknown rapper garbed in a coffee-hued t-shirt, faded jeans, and white sneakers, gestures toward the camera with the aspiration that this is the video that propels him to national recognition.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments