Ostinato Records' Vik Sohonie talks about latest Sudanese project – part 1

Ostinato Records founder Vik Sohonie is on a mission to revive music from countries defined by civil war, political dysfunction, economic malaise and an inability to cope with natural disasters. Sohonie has been documenting and releasing compilations and in the process brought fame to musicians who were once unknown, forgotten or neglected.

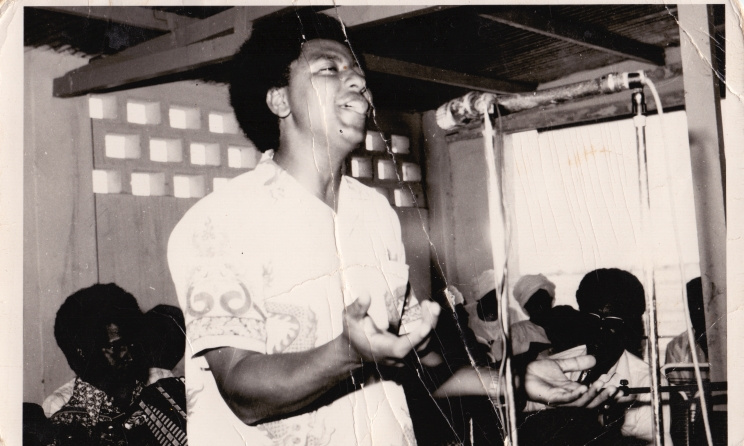

Abdel El Aziz Al Mubarak and Kamal Tarbas perform in Omdurman, Sudan, in the early 1980s. Photo: Kamal Tarbas

Abdel El Aziz Al Mubarak and Kamal Tarbas perform in Omdurman, Sudan, in the early 1980s. Photo: Kamal Tarbas Cover art for Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan.

Cover art for Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan. Ostinato’s Ahmed Asyouti, left, and Vik Sohonie, right, with singer Emad Youssef at his home in Omdruman. Photo: Janto Djassi

Ostinato’s Ahmed Asyouti, left, and Vik Sohonie, right, with singer Emad Youssef at his home in Omdruman. Photo: Janto Djassi Mohammed Wardi poses for a photograph in Khartoum, Sudan, in the early 1970s. Photo: Fouad Hamza Tibin and Elnour

Mohammed Wardi poses for a photograph in Khartoum, Sudan, in the early 1970s. Photo: Fouad Hamza Tibin and Elnour Legendary singer Salah Ben Al Badia (in black) sings at a wedding in Omdurman. Photo: Janto Djassi

Legendary singer Salah Ben Al Badia (in black) sings at a wedding in Omdurman. Photo: Janto Djassi Khojali Osman performs in Omdurman in the 1970s. Photo: Shihab Khojali Osman

Khojali Osman performs in Omdurman in the 1970s. Photo: Shihab Khojali Osman

In 2016, Sohonie released his first two records: Tanbou Toujou Lou (Haiti) and Synthesize the Soul (Cape Verde). These were followed by the Somali Sounds from Mogadishu to Djibouti mixtape – an archival teaser released ahead of his most successful release to date, last year's Sweet as Broken Dates: Lost Somali Tapes From the Horn of Africa. The album earned Ostinato Records a Grammy nomination for Best Historical Album. Although it lost out to Leonard Bernstein – The Composer under heavyweight label Sony Classical, the album, dedicated to Somali women, has become a resounding success, placing Sohonie on the radar of world-music aficionados around the globe.

Sohonie's latest project, Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan, is a compilation of the East African nation's golden music era of the 1970s and its brightest stars, who inspired some of the biggest names in Ethiopia, Somalia and the Arabic-speaking world. The music on the compilation, which is due to be released on 14 September, is largely defined by the leadership of Gaafar Nimeiry and the changes brought on by the 1989 military coup led by Omar al-Bashir, which dealt a death blow to one of Africa's most eclectic music scenes.

MUSIC IN AFRICA: Ostinato Records explores music from countries that have experienced trauma and displacement. Tell us a bit more about this advocacy.

VIK SOHONIE: Ostinato Records focuses on countries that are not in control of their own image, and as a result have been denied from presenting their true character to the world. The narrative from the countries I have covered demonstrate a great deal of historical illiteracy and perpetuate tropes and themes born from the colonial era.

Take Sudan for example. What do we know of Sudan really? Its ancient history? Its infinite diversity? Its profound and dynamic cultures? It’s unbelievable musical impact on the African continent? It was once Africa’s largest country before South Sudan seceded. I remember once a very well-travelled person telling me: 'Unfortunately, when I think of Sudan, I think of angry Muslims in the desert.' That image is the sum total of decades of unfair, single-minded coverage that focused on the colonial image of Sudan rather than what Sudan actually is – a land of the richest cultures on Earth.

Whether you’re a journalist, a filmmaker, or run a record label, you are a storyteller, and, as a storyteller, you should be able to craft the images and narratives of others in the global imagination. If you’ve been granted the privilege of being a powerful player in the image-making business and choose to use that position to perpetuate lies, half-truths, and a historical, myopic stories about those powerless to challenge your storytelling, you are no longer a storyteller but complicit in all the economic, political and physical crimes that the powerful inflict.

When did you begin to explore new music from around the world, and why was it so appealing to do so?

My label officially launched just two years ago in July 2016, but I guess you could say the foundation for it has been in the works since my family and I first packed our bags and moved from country to country. I grew up in many countries including India, the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, and the US. So when you grow up in different cultures, you learn the value of authenticity, and I always found music and food to be the most authentic representation of a people’s history.

Tell us about how your latest project – Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan. What inspired the idea?

I have been infatuated with Sudanese music. Sudanese music is one of the most revered in Africa and deserves a bigger audience. Its artists are loved from Mauritania to Djibouti. Artists like Mohammed Wardi were as inspirational as Fela Kuti in their political activism through their music. Wardi performed to a sold-out 60 000 arena in Yaoundé, Cameroon, to a Francophone crowd who did not understand what he was singing, but showered him with applause and love nevertheless. That’s the stature of what we’re dealing with.

Along with the album is a 20 000-word, liner-note booklet, which details the political impact on Sudan’s music. We will also publish video interviews with singers and, if they have passed, their families.

Did you collaborate with any locals in Khartoum, Sudan?

Yes. This album has a distinct Sudanese hand that has shaped it, which is exactly what a project like this called for and it would not have been legitimate without intimate Sudanese involvement, and we are very thankful for our Sudanese team. The project began with the guidance of Alsarah, a Sudanese singer based in Brooklyn. With her contacts we were able collaborated with Tamador Sheikh Eldin Gibreel, a famous poet and actress from the 1970s who personally knew the musicians featured on the album. Our good friend, Ahmed Asyouti, also played a crucial role during our day-to-day efforts.

What did you identify as the biggest obstacle while working on this project?

I would say running a music label of this sort is more about managing endless obstacles than anything else! We met singers who had renounced music for religious reasons and refused to license us songs or let us use their work in any way. It’s a real shame because it means some of the best recorded music in Sudan will not be available. We have to respect their wishes. That was perhaps the biggest obstacle.

However, Khartoum is a very, very warm and welcoming place, and I would argue that as far as major cities I have worked in go, its sacrosanct hospitality did make some steps in this project a lot easier.

Sudan's golden music era was largely defined by politics...

Yes. In the early 1970s to 1983 music flourished under President Gaafar Nimeiry’s rule but when he aligned himself with hardline religious leader Hassan al-Turabi, he instituted the September Laws, which enshrined an extreme interpretation of Sharia law. That was the first blow to music. The second came in 1989 when President Omar al-Bashir came to power and many beloved singers either went into exile or were detained and abused psychologically and physically.

By the mid to late 1990s, music had made its way back with a new record company in place, which was largely recording in Cairo and selling tapes in Sudan, Cameroon and Nigeria. Music was never wholly banned per se but there was constant incitement against the artistic community, which culminated tragically into the killing of some singers. This is a complex and very nuanced story, but as Dr Abu Sabib, a scholar in Khartoum, told us: 'In Sudan, the political and cultural are inseparable.'

Read part 2 of Music In Africa's interview with Vik Sohonie here.

Pre-order Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan here.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments