Brymo will save the Nigerian music industry

“Bros, na Brymo be that?” the man selling grilled meat asks.

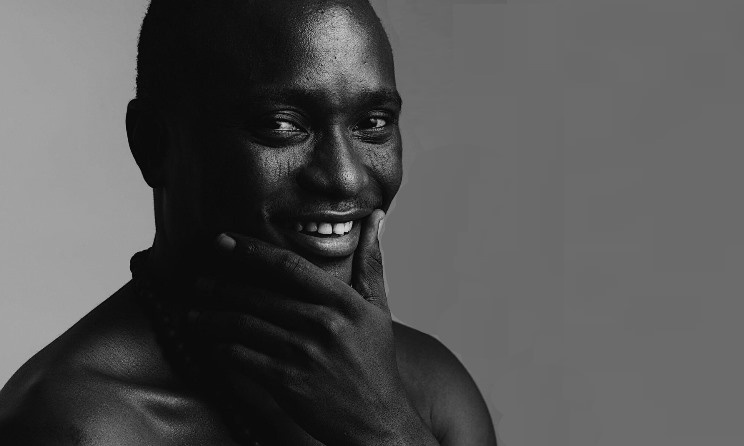

Brymo 'was lucky to have made mainstream hits' before going independent.

Brymo 'was lucky to have made mainstream hits' before going independent.

Indeed, it's the singer-songwriter in the driver's seat. The car is parked off a major street in Surulere, traffic is light, and Brymo is about to buy grilled gizzards. I tell the vendor he's right and watch his right palm clench into a fist. “Brymo!” he chants.

A woman nearby smiles and congratulates the man for the celebrity sighting.

Inside his car, Brymo cracks a smile, gets his gizzards, responds affably and drives off.

“I’m like Brymo without the mask,” he says to me.

This comes several hours after I first join him in his car outside of his manager’s office one morning. His car stereo is playing ‘Trouble in Bohemia’ by Jealous of the Birds. In keeping with the Irish theme, we'll later discuss U2, a band he's recently become a fan of.

To start, I recall an incident at the Lagos Government House. The organisers of an awards ceremony had asked the winners to bring their trophies for a photo session with governor Akinwunmi Ambode but a problem with the guest list caused so much of a ruckus that Brymo left before meeting the governor. When I remind him of the incident, he tells me I am the only person who has ever brought up the issue, that the organisers of the awards are likely to think of him as arrogant.

I tell him I found it a rather sad episode since he has to be the quintessential Lagos storyteller of his generation. Few songs have captured Lagos as well as ‘One Pound’, a single from Tabula Rasa, his fourth album. He nods his acknowledgment but says he does other things in his music.

“By the way, I have never shot a video outside of Nigeria before and it’s always been deliberate.” I go through his videos in my head. He's right. “I think we are not patriotic enough. Nigerians don’t know what it means.”

When I ask how shooting videos abroad is equal to unpatriotism, he tells me about growing up not watching MTV and living in a one-room apartment in Okokomaiko, Lagos. He watched TV with 15 other boys at the house of a neighbour. Each time a music video shot overseas came on, the boys would complain: why are these musicians shooting their videos abroad? The boys would then boycott the work of that artist.

“When I started, 80% of artists were doing this and I knew that Nigerians did not like these people. I have seen it five, 12, 20 times. Why are they shooting abroad? Why all these white girls? So it is interesting that the same Nigerians who want to leave and seek greener pastures feel betrayed when you don’t represent the country. Nigerians love Nollywood, they love Nigeria. Everything they are telling you in the media is a big fat lie. The real problem is that we are not organised. When you become an adult and start working, things don’t just work out because there is no system in place to help you."

In 2013, Brymo decided to do something about it. That decision would cause problems and endless media reports for him and Chocolate City, his label at the time.

"I had seen two sides of the story: first I had been with the people, now I had become a musician. I had scored hits but after scoring hits I had problems with the business. Chocolate City had problems with the business. EME [Banky W’s former label] had problems with the business. Mo Hits…Everybody who has ever been in the music industry cannot do actual music business. It is like a communist country: there is a bar that the elite, the rich have created for musicians and for entertainers. They take care of you and decide what they give you.

“But it is my country and if I leave and return I still want to have a royalty collecting body and a good price for my album. And these are some of the simplest things you need to do for the music industry anywhere in the world."

Instead of running, “like everyone else has done”, Brymo decided to create a system, he says, from scratch because "I'm already famous". This has meant using the gig scene, perhaps the only fully functional system for Nigerian musicians.

“I am going to make freaking amazing music and I’m going to become the best performer in the country so that the gigs can fuel my work. And as long as I can gig I can make money enough for me to be able to start distribution and chase royalties from zero. Of course, I’d have to leave the radios alone for now.”

Everybody else, though, is fair game. His team reports blogs hosting his music to Google. “I can make a video for everyone to watch but the audio is only available for sale,” he says.

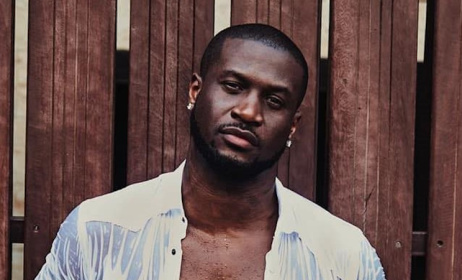

At this point, we meet up with Brymo’s manager, a guy nicknamed Black. Shorn of hair and with a body that looks like an asset in a fight, Black looks vaguely threatening. He turns out to be quite genial. There are books around his office, including one on Michael Jackson. He asks what we’d like to drink. Brymo wants wine: “Sauvignon.” His emphasis on the French pronunciation provokes laughter. Black disappears.

“Between us and radio, it’s a working relationship, so we have to work it out. And I think that was even taken care of by COSON before they had their internal problems and they were not transparent enough." But COSON needs to take advantage of technology, he says. "That would mean musicians have to release music through a process that would help COSON tag the music.” He explains that to release an album with a foreign label, he had to wait three months because of American regulations. But how transferable is that to a culture addicted to making music and releasing it immediately?

“How can we be used to mediocrity?” he shoots back. “We have to fix it. People would then start to put more thought into the music. We can adopt a month or three weeks before the release of a song or album. That way the music can be tagged.” He counters the idea of blogs hosting music as publicity, saying it is not like music blogs posting a particular song twice or more times in a week like radio stations do.

As for Twitter users promoting songs, the trouble is it makes judges of mere social media users. "Over time, the influencers only like musicians who bring business to them. You can't blame them but there are days when they should use their judgment wholeheartedly, but they'll give a judgment based on personal relationship." He admits that it doesn’t translate into power in the real world, but as anyone online knows sometimes the appearance of power is power itself.

"Same thing on radio. Over time, they won't play music if you don't pay. But if you play music you love, automatically musicians will make music they love and then people will start listening to music they love—and then we have fixed the problem. In fact, to fix the economy everyone has to get jobs they love."

From here, he goes on to talk about "an energy war" and why it is important to "do what you love, be friends with who you love, f*ck who you love". I tell him that might be easier for a famous man.

No, he says, love isn’t so easy for a famous person. But yes, he admits, “being famous makes it easier for you to get sex. That is the only thing it guarantees. A relationship is a different ball game.” There are women who say no because they believe there are other women, but “there are women who don’t mind".

This may be a banal occurrence for any man with some fame and success, but Brymo approaches it philosophically. He tells me when faced with such a situation, one has to decide between what one wants to do and what one should do: It is the balance between both that makes a people successful. African societies have too many powerful people who do what they want; but the West, he says, has found a balance. “They struggle to make sure what people must do and what they want to do are in alignment. People still get away with stuff but they try to keep the balance. They sell their albums for $9.99, even in South Africa.”

It is quite a jump from the philosophy of sexual relations to anthropology to album prices but there is no stopping him now. “We say we can’t do it because our people are poor. Why are they poor? If they sell a Nigerian album sells for 2 000 naira [$5.50], it is not a lot of money,” he says.

Technically, yes, but...I ask if he is considering the national minimum wage when he converts the South African unit price for an album from the rand to the naira.

He scoffs: “At least 5 000 people every Friday night spend 5 000 naira every Friday night. Let’s leave those ones [at clubs] like Quilox and those big boys. People spend that much to get drunk and once that night is over, 5K is gone. They don’t take the bottle home.

“But music that someone wrote and went to the studio to record, mixed and master and made a Clarence Peters video for 2 million plus a payola media that would charge us for promotion—and after doing all of that you buy the album for 200 naira and play it for three months before it cracks. The next day, this Nigerian artist walks by and Nigerians will say, ‘After the plenty money he made from that hit he doesn’t have money any more’. The artist will then pretend that he made a lot of money and he blew it. But he didn’t make a lot of money—your album sold for 200 naira.”

I remind him that albums don’t sell quite as much anywhere in the world.

“That’s not true,” he says. “Since my new album Oso dropped, half of the gigs I have done in the last three months are mostly gigs that I did in collaboration or for free. I have lived off record sales for $9.99 for the past three months. Every penny I have spent on my Organised Chaos that is coming and my London show is coming from my royalties and you people keep saying albums don’t sell.”

When I ask for numbers, he says, he doesn’t have time to count. “iTunes doesn’t give you numbers. They only tell you how much you are getting from this single or that album. Even locally, Spinlet has paid us hundreds of thousands of naira over the past four, five years. Spinlet has paid me more money than Alaba and I sell it for at least 500 naira on Spinlet. I went to Alaba with MD&S [his third album]. They said they sold only 10 000 copies. And the money was supposed to be about 65 000 naira because we got 5 naira for every CD sold.”

He sees that I'm surprised. "What do you think I was talking about? They sell it for 200 naira. The guy selling it in traffic makes more money per album than me, the musician who owns the album.”

This is because Alaba marketers sell the CDs wholesale for 60 or 50 naira. “CD, package, music inside the CD, tracklist, graphics, everything is 200 naira maximum. If you buy it from traffic, you can get it for 150 naira,” Brymo says.

Politicians and radio people have been disrespecting artists by claiming Nigerians don’t have money, he adds. “But they want to dance to my music. I got high and drunk and was observing things in the club and I wrote it down and it worked and you love it and you don’t want to pay me for that. And I am burning out—every time I make a hit you guys remind me that I am getting old and one day you will replace me with someone younger and yet you don’t want me for that period.”

It is clear Brymo has given the issue a lot of thought. He is agitated but still cordial as he continues. “How come A-list Nigerian artists perform poorly live and still get paid millions?” he asks. “It is because we have become tools for some kind of racketeering because I can easily push money from my company and hire a musician to perform and pay him a nice amount and do other things. It is about other things. If it’s about the performances, Nigerian artists should not be getting paid for performances because it’s mediocre performances.”

Complaints about mediocre performances often dot the social media landscape after live events featuring Nigeria's biggest pop acts, but people behind these complaints are reluctant to acknowledge that part of why anyone pays a star to perform is to see the star in the flesh. If, as some might say, the show is secondary to the business, then the artist's presence is more valuable than the performance.

Brymo is having none of that. He insists on the Nigerian music industry existing as a front for corrupt practices. “The same elites think that Nigerian music is shit," he tells me. "When it is time to really enjoy themselves, they’ll take a flight to London to watch Coldplay. I have at least five friends on the Island who go out and see opera, Bruno Mars, Adele, MJ before he died. They know the music is shit. There is no value for the music. The music industry is just an excuse for money to move around, so we keep it that way and keep doing business with it. There is no value in the music itself.”

But there is value in stardom. “Valuable stardom is corruption,” he says. “It is just fame and if you are going to transform fame into money, you are going to be corrupt. Tell me how to transform fame into money.”

I give the example of club appearances by famous persons. “You can’t make so much money from that,” he says. “I have done club-hosting a number of times myself. It is one of those spaces we get money from but if we do what I am saying, if we sell albums for 1 000 naira, 2 000 naira, record labels will start planning for their artists to sell 100 000 copies.

“If record labels can project profits then artists can make more money. Managers will make more money. You know that over 80% of managers don’t have cars of their own? I can take my fame and make powerful friends and milk it and do things for myself. How about the manager, the producer, the dancer? How about everybody else that makes my music work? That is why the music business is not successful. Because those other people are not so famous and they can’t milk their fame. At 2 000 naira, Chocolate City can now hire 15 people and really be a record label because Brymo’s album sold 500 000 copies.”

Is it still possible to sell that amount of records today? “Of course, 100 000 is possible,” he says. “At 2 000 naira a record, if you sell only 10 000 copies, you can make 20 million ($48 000). If the label spent 2 million naira to record the album, it is recouped. If they spent 5 million naira to shoot three videos, it is recouped. There can never be a loss in the business. Artists will no longer pay courtesy visits to any corporate body, thereby reducing their worth. The corporate bodies will have to go through the right channel because even your manager is rocking a nice [Toyota] Camry. You can take a loan because the banks know that the music industry is truly bankable. Musicians will be able to tell politicians, 'stay for your office because your shit is rubbing off on me'."

Black returns and proceeds to fill glasses. Brymo is too wrapped up in what he is saying to confirm if it's indeed sauvignon he is getting: "Artists want to be rich and if the price improves, they will spend more time on the music because it is a dream they are selling." For this to happen, he says, Nigeria would have to crush piracy.

He explains that there is a danger when an artist fails to get rewarded for his music directly. "When somebody gets famous and that song doesn't amount to payment for streams or downloads or mechanical royalties, what happens is that, say, Black starts the first edition of a festival and gets sponsorship from a big company to help him get a great venue and then pays me 5 million naira and gives another person 7 million and so on, record labels will call him and ask that he puts their artists on the stage.

"When the next show comes, Black will not pay anybody. As the years go by, the festival becomes a bigger brand and musicians will beg him to put them on. In five years, everybody performing will be doing it almost free. That is the problem when artists can't earn from what we can control, the song or album. But how much you want to pay me for a show is up to you."

Brymo is aware that big acts can control payment for their performances but he is tired "of isolated cases, of D'banj being the biggest popstar for 10 years, followed by a rapper. In the alternative corner, I seem to be the only one that knows how to milk it and go about my business. Ninety-five percent of them are still being shunned."

I ask what he did differently. "I just got lucky," he says. "I was lucky to have made mainstream hits, so people already know me and can't ignore me so much. Then I've had to put in work to keep delivering the goods." Having released five solo albums and one compilation record since 2012, Brymo is very productive; Olamide might be the only artist with more goods in the same period.

Brymo is also tired of an industry dependent on handouts. "Nigerian music must move past that phase where politicians and the rich are taking care of musicians like King Sunny Ade," he says. Clearly aghast, he tells me Fuji great Sikiri Ayinde Barrister sold the master of his album in 1996 or 1997 for 1 500 naira. He offers this as proof of the smallness of the Nigerian music industry.

To enlarge this economy, Brymo called on musicians to avoid voting for any politician without a plan for the music industry. Someone responded with a derisive comment saying the government needed to focus on other things, after all, fraudsters are already sponsoring the industry.

"So it's the same f*ck*ry since I was a child when they'd say Pasuma or Wasiu were singing for drug dealers. It is the same thing we have in the industry today. Nothing has changed. But I'm saying we can create a balance by fixing the numbers. The government will earn taxes. But now I hear the government is saying entrepreneurial musicians don't have to pay taxes. Why?"

For Brymo, this waiver is merely a way for the government to shirk its responsibilities. "I want to pay taxes. Come and fix this shit so I can pay taxes."

But that is only one part of his complex solution to the music industry's problems. Before we get in his car again, before Brymo takes off his Brymo mask, before he speaks at length about Chocolate City and his album Oso, before the woman on the street praises the gizzard vendor for spotting the star, Brymo gives me the two other parts of the solution.

"Rich people need to come out with this money and build infrastructure," he says coolly, a glass of wine at his elbow. "And the artists have to shut their mouths and think and reflect and observe."

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments