Interview: 'Nigeria's music business is a mess' – part I

One of Nigeria's oldest record labels was established just after the country acquired independence.

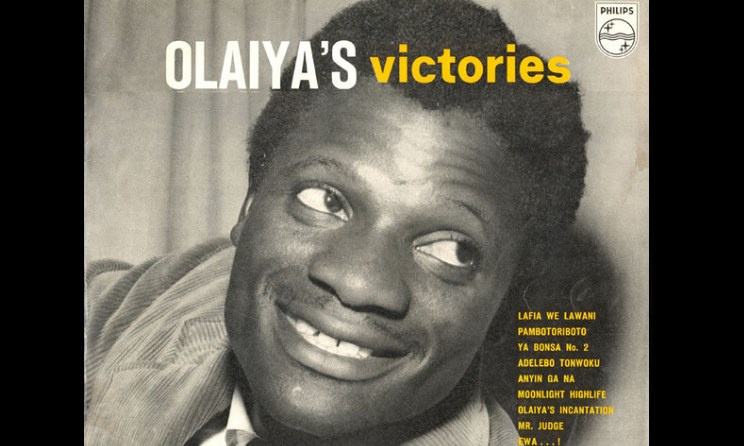

The cover of a Victor Olaiya album released by Premier Music, which was known as Philips West Africa Records in the 1960s.

The cover of a Victor Olaiya album released by Premier Music, which was known as Philips West Africa Records in the 1960s.

Premier Music started as Philip West Africa Records in March 1963. Then it became Phonogram. The Dutch label Polygram acquired major shares from Phonogram in the early 1970s, and took over operations and name.

As Polygram, the company did business till the early 1990s. Then the economic downturn following the infamous Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) forced Polygram out in 1991. That exit resulted in two developments: the name of the company changed for the last time and Nigerians took over the company's operations, with the present managing director coming into the position in 1994.

One recent evening at Freedom Park on Lagos Island, the company's business manager Michael Odiong spoke about Premier Music's challenges, the music industry's technological changes and the relationship between today's music and music from decades ago.

MUSIC IN AFRICA: In the 2000s Premier Music attempted a comeback. This now appears to have been shortlived. What happened?

MICHAEL ODIONG: We signed five artists. Three of them released their albums but the remaining two couldn’t. Their contracts expired before anything could happen. We saw that five artists was not sustainable and had to restructure. So a lot of things happened between 2008 and 2012. The Nigerian situation made it very difficult. We had about 30 radio stations. How do you start promoting on different stations when these presenters ask you for humungous amounts of money? It is a major problem in the country.

Sometimes we used our own personal money to treat these DJs and presenters. It was quite challenging and frustrating because at the end of the day, your music isn’t played the way it’s supposed to be. I’m not a musician but because I work for a label it was my duty to make sure that promotions were done. And I wasn’t getting the kind of support we expected from the radio stations and even friends that were DJs. They asked for too much money.

At the end of the day, most of the artists we signed fizzled out, though videos were trending at a point in 2008, and they were all unique. The trend of having more highlife singing in Igbo from the Phynos and the Flavours and the rest of them was actually started by the likes of Zbyte [one of PM's artists].

Is it possible that PM was trying to capture the past instead of looking forward?

It wasn’t really capturing the glory days. What we did was take the strengths of artists from various genres of music: reggae, highlife, R&B. It is now a case of who does it first and people realise or discover. Flavour’s style is not new. But because he has been able to attain the spotlight, people attribute his kind of music to him, but really it wasn’t. If you listen to a Chris Mba from the 1980s, you discover that what Phyno and the rest of them are doing has been done. The percussion and everything. One of our slogans at Premier is 'Everything New is Old'.

The artist might feel, 'Oh! it’s a new thing', but for us, we know where the sound is from. Their producers know the origin of their sounds. I’ll give you an example. The late MC Loph released the 'Osondi Owendi' remix [originally by Osadebe], the major song that made Flavour's name. The rights belonged to us. We pursued it and I finally met MC Loph. I said, 'How could you? Did you search? Did you ask?' He said he left everything for the record label and when the label said it couldn’t get it, he went ahead. He apologised and I said, 'Look, we have to find a way round this because you have infringed on our right.' When he released another song sampling Sir Victor Uwaifo, I was one of the people who he called. He said, 'Look oga come and listen to this one. Abeg how do we want to do this?"

Unfortunately, he died before that song was released. Ten years back we would have said the music industry was still growing. People did not understand what right ownership was. Not now. No producer or record label will say that they do not understand copyright. But sometimes you look at these things and you say, 'Is this our priority?' Timaya did a remix with Ras Kimono. We didn’t know anything about it. But two years later, he sampled Blackky on 'Dance' with P-Square. We had an agreement.

You say going after copyright infringment is not a priority. What is the label's priority?

We are making sure that the Premier Music catalogue is digitised and available on every digital platform and not just about Nigeria. MusicPlus? Cloud9? Boom Player? You would find our songs there. We have more than 2 000 albums. These are songs recorded from the 1960s down to the late 2000s. We have gotten licence to be value added service providers from the NCC [Nigerian Communications Commission]. That gives us the licence to do business with all the telcos. So we handle our own caller ring-back tunes, short codes, everything digital. Soon we can start thinking of signing new acts because no matter how digital you go, if you do not have a new act you are not a functional record label.

What challenges have dogged Premier Music since Nigerians took over?

By that time piracy was at its peak. Other record labels had to quit, but we stayed.

Is there an answer today? The Performing Musicians Association of Nigeria (PMAN) and the Copyright Society of Nigeria (COSON) have made interventions but nothing seems to have worked.

The problem of piracy is not just a Nigerian thing. America has piracy issues but it is difficult to pirate their works. What we are not doing right is: Number one, we don’t have a structure. And as long as you do not have a coherent structure, both from government and the industry, you will run into issues. What are the laws to fight piracy? There are laws but they’re just dormant. If you do not enforce those laws, those laws will remain dormant.

Secondly, is the industry united enough to face the executive, legislature and judiciary? PMAN has three, four factions. COSON, MCSN [the Musical Copyright Society of Nigeria], everybody seems to be doing their own business. It’s no longer for the common interest but for individual pockets. As long as you do not have a structure and united body to fight piracy, the government will not do anything about it. Look at the National Assembly. You have lawyers, accountants, surveyors, you have all sorts of people there. How many entertainers are in the National Assembly? We don’t have any.

So if I talk of piracy, the National Assembly will not understand. They’ll say, 'Look, are you not an entertainer? Look, we’ll pay you. Come and sing.' But they do not understand that entertainment is the next biggest thing. In fact, if not bigger than oil. You need professionals in the industry to be part of the executive, to be part of the legislature. We need entertainment lawyers that are enlightened and travelled to be part of the judiciary...

Comments

Log in or register to post comments