What might Fela think of Tekno’s Rara?

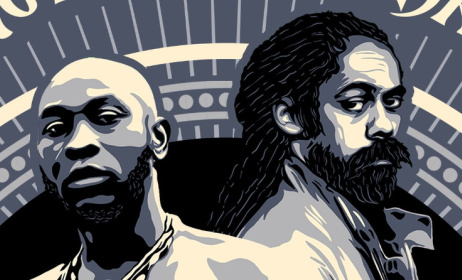

After ThreeWiseMen and Wizkid in recent times, Tekno is the latest Nigerian musician to have his say on Afrobeat.

Tekno. Photo: Billboard

Tekno. Photo: Billboard

Producer IKON’s interpretation of Afrobeat on ‘Bastard’, ThreeWiseMen’s underground hit from 2012, is certain to make He-Who-Cannot-Die leap up from his undeath.

It’s not that the muted hit from 2012 is without its problems; BlackMagic, after all, isn’t exactly renowned for his ability to hark to the party line of his songs. Fela would wince midway through the first verse, where BlackMagic and IKON’s fascinating lyrical ping-pong degenerates into a mishmash of mismatched, mis-stitched parts from which it scarcely recovers.

But 'Bastard' is that rare Afrobeat spectacle. That title alone situates it in the direct lineage of feisty Fela titles like ‘Zombie’. Like ‘Zombie’, ‘Bastard’ emerged from a near-fatal confrontation with uniforms (this time the police), as IKON has explained.

Fela might feel some ambivalence at ThreeWiseMen’s invocation of the koboko given the wonders it performed on his back, but realising that its use here mirrors the use to which Jesus Christ put a whip in his Father’s house is sure to ease that sense. ‘Bastard’—at least what part of it is consistent—is pointed socio-political critique. The percussion is minimal, limited only to snares and hi-hats. A meaty piano tiptoes through that sparse undergrowth like a cantankerous cartoon character. Later an assembly of horns obliterate the beat, declaring their martial intent, before retreating to return again.

The shrill chants from Fela’s oeuvre are here too. ‘Bastard’ is Afrobeat with a (hip hop) kick up its butt. As the song closes, TWM appropriate and revamp the bawdy title of a Fela tune from way back in 1971. In TWM’s version, “let’s start what we have come into the room to do” becomes “let us start what we have come to the world to do”, rendered in a plausible imitation of Fela’s voice.

Fela, it needs to be said, would approve.

Wizkid’s ‘Ojuelegba’ is remarkable specifically because it reminds us that Afrobeat is simply music and not necessarily politics. It is the culmination of the depoliticisation of Afrobeat Wizkid began in ‘Jaiye Jaiye’. It is a cheeky take on Afrobeat and Fela would certainly appreciate the cheek now that he’s above the fray and can see the range of his own musical practice better.

‘Ojuelegba’ is Afrobeat in vamp-only territory, a cordon sanitaire established to keep out most strays. It is eight bars of beat looped repeatedly over itself, and not much else. It’s the sort of canvas over which Fela painted his saxophones, trumpets and horns in quick, keen scribbles. Fela’s beloved brasses are notably absent, as are the shekere, maracas and sticks. The result is a rounded rectangle, an Afrobeat whose edges have been blunted. The song’s tempo is not frenetic; it proceeds at a pace as subdued as any of Fela’s more contemplative, late 1980s tracks. Where Fela’s singing voice is monstrous and forced, Wizkid’s is easy, mellifluous.

‘Ojuelegba’ does not bite; far from it. Instead, it is sweet swing with a tinge of sting. Lyrically, ‘Ojuelegba’ is sort of like Wizkid’s ‘Started from the Bottom’, except that Wizkid lacks Drake’s narrative powers. A brief acknowledgement of Nigeria’s urban predicament—“ni Ojuelegba o/my people suffer”—soon gives way to a celebration of the good life. If Fela’s Afrobeat is lemon, ‘Ojuelegba’ is full-on lemonade.

A quick word on lemons and lemonade:

Fela’s Afrobeat can and should be split into style and ideology as Tejumola Olaniyan and Michael Veal demonstrate in Arrest the Music! and Fela: The Life and Times of a Musical Icon respectively. This split allows us to better understand the uncanny complementarity of both strains of Fela’s craft. After Fela realigns with his roots, his politics gain a gradual complexity, so that by the mid to late 1980s, he can advance eloquent critiques of the postcolonial condition of the African state. A most remarkable turnaround for a fella whose sense of identity was only rehabilitated by a searching African-American woman.

Fela’s ruling ideology, as exemplified by his lyrics, was scathing as it was scalding in its evisceration of both subject and object of power. This is the Fela in the popular imagination: the nonconformist gadfly. If you had any sense in you, Fela wanted to goad you, make you grimace. Of course squaring this goading with Fela’s primal desire to make us dance should prove fertile ground for reception theorists.

Fela’s style—the music in the music—complements his ideology at a visceral level. How else is one to explain the lacerating edge of Fela’s beloved brasses darting forays into the dense patchwork of varied percussions and strings he assembles? That patchwork, it can be argued, is a pretext, the stage for Fela’s parading of horns and saxophones. These brasses, the lyrics, Fela’s unseemly voice, the biting wit, the bewitching chants, unite to make this strident thing, this trenchant yet piquant whole; this infectious toxin. It is lemon at its lemonest. If life gave this Fela lemons, he made them unripe. It bites, but we kind of like it.

What Fela would make of Tekno and his 'Rara' is less straightforward than what he would of 'Ojuelegba'. The song's producer Selebobo follows Legendury Beatz, producer of 'Ojulegba', in sonically purging Afrobeat of its edge. The edge here is in Tekno’s lyrics, although if 'Shuffering and Shmiling' is anything to go by, all that invocation of Oluwa’s blessings a third of the way through 'Rara' is sure to rile Fela.

‘Rara’ is littered with Fela allusions: “rara o” is almost a sonic doppelgänger of the “rere run” from ‘Everything Scatter’, and ‘perambulation'—sound and fury signifying nothing—is straight off ‘Perambulator’. The “follow follow” in “dem go dey follow follow” is from ‘Follow Follow”.

There’s a nod to nationalism too, not cultural this time but economic—“invest for your country.” Fela of course became far too woke to forget about the big things in dealing with the small, whatever Tekno means by this; Fela’s method, as exemplified by ‘I.T.T’ and ‘Beasts of No Nation’ among others, was to link the local to the global, and vice versa.

Overall, it is fair to say Fela might be put off by ‘Rara’; there’s too much of a sycophantic undercurrent. ‘Bastard’ and ‘Ojuelegba’ are original, iconoclastic takes on Afrobeat in their own different ways, and no one appreciated iconoclasm more than Fela.

Tekno, on the other hand, seems to want to ride the wave of a resurgent Afrobeat without noting TS Eliot’s injunction on the need to extend tradition by imbuing it with individual talent, an injunction Fela himself imbibed in his complication of highlife with jazz, and the birth of Afrobeat proper from his battle with the uncritical commonplaceness of Afro-American soul. The question Fela might ask Tekno is this: Why switch genres just because you want to sing a f**king political song?

Cue a tongue-tied Tekno.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments