The role that Zimbabwean music could be playing

Zimbabwe today is on the precipice. Although we are a happy and warm people, a lot is wrong with our politics and economy. Detailed information on the problems Zimbabwe is facing is awash on the Internet and elsewhere; I will not delve much into that. From where I stand, however, one of the greatest tragedies we face as a people is that voices of dissent have been systemically and almost effectively muted. When a people cannot talk or sing openly, then the essence of community is no more. Our musicians are very careful not to sing openly without the use of idioms and at times this betrays the message being conveyed. Speaking in hushed voices threatens to shred the little that is left of our social fabric.

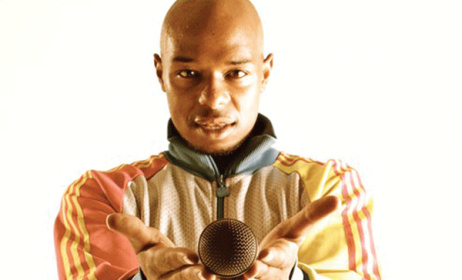

Winky D. Photo: HERITAGE FUSION

Winky D. Photo: HERITAGE FUSION

I understand that the current wave of protests in Zimbabwe are engineered via the shield of social media. The fight against a systemic rot like that being faced in Zimbabwe should not over rely on copious, important, yet often misrepresentational Facebook videos and rants to be effective. Rather, the authoritative voices and cogent articulations by us the ordinary Zimbabweans in the form of accessible cultural activities such as song, stories and tales should be seriously considered. These have the potential to raise the urgency in facing the repressive system head on. The idea is to use the affective power of dialogue, songs, and stories to rethread the tattered Zimbabwean communities. Of course, other political processes will be running parallel. This is not to imply that music is the end to the problems we face. But it is one of the options we can explore to strengthen our weakened social capital and diminished interpersonal trust in our communities.

We should be cognisant that in indigenous Africa, music was conceived and applied to play critical roles as an intangible force that managed societal systems, coerced humanity consciousness and sanctioned deviations in the conduct of stable as well as sublime societal living. Therefore in Zimbabwe, music should continue to negotiate the drastic temper of governing authority that is intolerant of dissent and criticism. Paul Madzore, a former, Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Member of Parliament,, has been consistent in this regard.

In his new songs Bond hatidi, Zimbabwe Yadzoka, and Takashinga, Madzore does a good job of explaining and addressing contemporary political and social concerns in Zim, and making pertinent contributions to the debate around the ill-fated bond notes and unified citizens action. I particularly, enjoy that his songs are done in the call and response style, which by the way in non-studio settings can only be achieved by more than one individual. What this means is that music effectively becomes an experiential platform through which people can meet and dialogue. Madzore’s music is easy on the ear and bold, while the subject matter he sings about is very important. Through song, he has managed to speak on the totalitarian and oppressive government of Zimbabwe and its impact on our everyday lives. His chosen music and method is very simple albeit not simplistic. Anyone can do this, and they can do it at any setting.

Not everyone has the courage to sing openly like Madzore or be clever about it the way Winky D subtly reminded youth that they are underachieving victims of the system in his songs ‘25’ and ‘Daddy’ from his 2016 release. However, all of us can and should listen to this music, either in our personal or in public spaces in Zimbabwe. It is important to spread the music.

What I am advocating here, essentially, is a return to source, where solutions to our common problems are communally owned. There is a plethora of activities that our communities can do together. For instance, we can embark on clean-up campaigns, or decide to fill-up potholes as communities. While at it, we can compose and sing protest songs. I don’t think the system will stop us from mending some of the community problems and work songs are not a criminal offence. Subsequently, some of the songs will be incidental music serving as reminders of what we face and what we should do.

We also need to be wary of the fact that the deciding vote is going to come from young people, most of whom are Zim Dancehall fanatics. Challenge is this type of music is losing its currency. It seems as if ZANU PF have stopped propelling the genre. The genre’s popularity did not just lie in that it was a ghetto movement, the government deliberately channelled resources to propelling resources to popularising the genre as a strategy to give youth a false sense of belonging and employment. Now that the youth know that not all of them are going to be successful singers and the leading lights are singing about popular issues affecting ordinary Zimbabweans, the system is doing little to nothing to hype this music through print, online and broadcast media. There is therefore an urgent need for us to think around harnessing the youth energy in this music .

Comments

Log in or register to post comments