An Ode To Sankomota

Kingsway, Maseru’s main street, should have been bustling with lines upon lines of mourners queuing to touch his casket. The airwaves should have been saturated with the beautifully haunting textures of his compositions. A public holiday should have been declared to honour his immense, immeasurable contribution to the art of music-making. But alas, this is Lesotho, and we are not particularly well-known for recognising our heroes. 27 November 2003 marked the end of an era: Frank Mooki Leepa, guitarist and frontman of Sankomota, passed away.

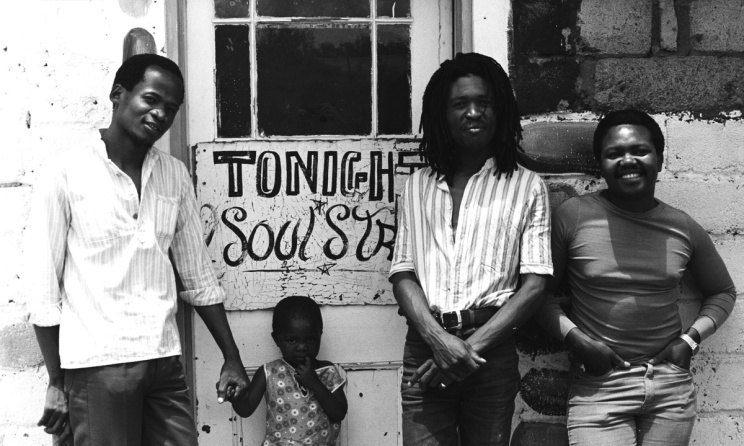

The history of Sankomota is as long as it is interesting. It is a dense tale punctuated by varying degrees of bad timing, bad decisions and bad luck. Starting out in 1975 under the name Uhuru, copyright claims from the Jamaican Michael Rose’s Black Uhuru meant that they had to re-focus their musical energies as Sankomota. It was no easy feat considering that Uhuru was already well-known across the Southern African region. Adoring followers in both Lesotho and South Africa could not get enough of their groove-oriented African melodies, skilled musicianship and ‘get-up-and-dance’ dynamics.

According to Leepa, Sankomota was the name of a Pedi warrior who lived during the times of King Moshoeshoe. The band adopted it, re-imagining the moniker as a symbol of unity, regardless of one’s tribe. Notions of belonging were overlooked in favour of a more inclusive sound. The lyrics often contained entire verses sung in Zulu, Pedi, or Sotho. The music – stark and dense in equal measure – carried elements of the band’s influences: melodies criss-crossed mbaqanga’s technicality, jay-walked on reggae’s combustible street-corners, and shaved off jazz music’s jaded vision to form an amalgam of what Frank referred to as “malo” (spirit/soul) music. This is a band that has served as my sanctuary whenever pop music seemed to lose track. Leepa’s erudite arrangements, complemented by Tsepo Tshola’s moving vocal incantations, are excellent from any vantage point.

Erstwhile frontman Tshola was to leave the band in 1991 to pursue a solo career, leaving Leepa to take the reins – yet another blow. This, however, only seemed to inspire the remaining cast – Black Jesus, Budhaza Mapefane and co-founder Moss Nkofo – to soldier on. They were still under the leadership of Leepa when tragedy struck, yet again, in 1996. This time around, it was a road accident while the band was on their way to Cape Town. Some members passed away in that crash. I can still vaguely recall the haunting images of the wrecked taxi on the news bulletin that evening.

To me, Sankomota represents memories of a childhood well spent: the tapes on long trips, the lazy Sunday afternoons, and the constant rotation of ‘Stop the War’ and ‘House on Fire’ on the radio. Sankomota’s music was significant in that it seemed to unify an entire nation. Their concerts are remembered as celebratory occasions with multiple encores. They reportedly even outshone American jazz giant Dizzy Gillepsie when he performed in Lesotho in the late 70s.

Their self-titled debut album was recorded in Lesotho in 1983 with the assistance of Lloyd Ross’ Shifty mobile studios. My joy, a few years back when an acquaintance showed me that very first album – an LP still in mint condition – cannot quite be captured in words. They went on to release five more albums, the last being Frankly Speaking in 2001. The album had its moments (such as ‘Another Accident’ and ‘Moonlover’, featuring guest vocals from the late Nana ‘Coyote’ Motijoane) and while Leepa’s prowess still permeated the grooves, the band had somehow disintegrated into a shadow of its former self. Too much had been chipped away at the edges, too many struggles endured, too much had been lost. My favourite album to this day is After The Storm. Every song evokes strong memories: me, a youth in the early 90s fascinated by the sounds produced by one of the best musical exports to ever emerge from Lesotho and make an impact on the broader jazz community. It might not have been their best work, but it was my first encounter with their disarming spirituality and polished musicality.

At his funeral, promises of an institute dedicated to his memory were made. Delegates, musicians and ordinary citizens gathered to pay their last respects. In retrospect, it may seem that we betrayed the memory of a legend. Yet with every Sankomota song played, with every anecdote shared about the collective’s genius, the legend that is Frank Leepa and the gargantuan force that is Sankomota lives on. I shall finish my ode with these words from their song, ‘Malala Pipe’: ‘I believe you were born for greatness, the light in your eye is [the] spark of god.’

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments