Protest music in South Africa

By Robin Scher

The history of the struggle against Apartheid is traditionally told through the retelling of events and biographies of individuals. Perhaps equally as relevant, yet somewhat ignored, is a telling of history through song. As one of the most widespread forms of mass resistance during the struggle, the array of protest music that emerged as early as the 1920s provides an alternative documentation of the struggle against Apartheid. From the early choir music of the Ohlange Institute to the pop hits of late 1980s, the evolution of protest music mirrors the changing shape the struggle took, from humble beginnings to a worldwide call for an end to the segregationist system embodied in a single message - ‘Free Nelson Mandela’.

Reuben Caluza and the Beginning of Struggle Through Song

The struggle started politely. The earliest music expressing discontent emerged from the Ohlange Institute, which was founded in 1901 by John Dube, who would go on to be the first president of the South African National Native Congress (SAANC), later to become the African National Congress (ANC). Ohlange served as a place of learning. Influenced by a visit to the United States, the music produced by the Institute, which came to be known as iMusic, reflected this. Grounded in European and American church music, these early protest songs were mere grumblings, with no call for direct action.

Reuben Caluza, a pupil and later a teacher at Ohlange, composed much of the early iMusic protest songs. Through national choir tours of the Ohlange Institute Choir, these songs would keep South Africans informed. As the songs were also in isiZulu, white officials were not able to understand what was being sung. It was in this manner that Caluza was able to compose songs that complained about issues of the time. For example, ‘Umteto we Land Act’ aimed to spread awareness of the 1913 Natives Land Act, which restricted black land ownership and served as one of the foundations of apartheid, and to promote the ideals of the SAANC, which had formed to oppose such racist policies.

Despite the best efforts of the SAANC, the Land Act remained, further entrenching the unequal distribution of land. As an indirect result of this, music found a new means of distribution: the migrant worker. With the Second World War seeing a generation of young white males sent off to fight, the demand for labour on the gold mines increased. Black workers from around the country flocked to Johannesburg and soon a vibrant community sprang up in the central neighbourhood of Sophiatown.

Wartime innovation saw the introduction of the transistor radio. The streets of Sophiatown were soon jiving to Duke Ellington and the sounds of jazz and ragtime. The gentle church tunes of iMusic had no place in the frenzy of this place and protest music began evolving to reflect the prevailing trends.

Caluza, realising the inadequacy of iMusic for expressing the growing resistance felt amongst the black population, began composing in what would become known in protest music as iRagtime. Believing this style of music to in fact be more compatible with Zulu speech patterns, Caluza was able to deliver some of the most direct resistance through song to date. A notable example was ‘iDipu eTekwini’ (Dipping in Durban), a song Caluza composed dealing with the dehumanising practice of human flea dipping required for workers from rural Natal wanting to work in Durban.

Dorkay House and King Kong

Following the rise of the National Party to power in 1948, the 1950s saw the implementation of several new apartheid laws. The government increasingly attempted to destroy the black middle class, as well as their ability to protest and express themselves. Intrinsically linked to this were restrictions on recording music, whereby black musicians were limited to recording at the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC). As such, for a time, creative freedom for black musicians was largely taken away.

Realising the need for such a space, a group of artists under the wing of a white man named Ian Bernhardt helped form the Union of South African Artists in 1952. Their aim was to protect black artists from exploitation. This group, which later came to be known as Union Artists, operated out of a dilapidated building at the southern end of Eloff Street in downtown Johannesburg – Dorkay House.

Stepping into Dorkay House during the late 1950s, one would be likely to hear the piano sounds of a young Dollar Brand, later known as Abdullah Ibrahim, perhaps mingling with Miriam Makeba’s vocals or Hugh Masekela’s trumpet. Reflecting on this time in the 2002 documentary Amandla!: A Revolution In Four-part Harmony, Ibrahim recalled: “The thing that saved us was the music. The music was liberation music because it was about liberating ourselves.”

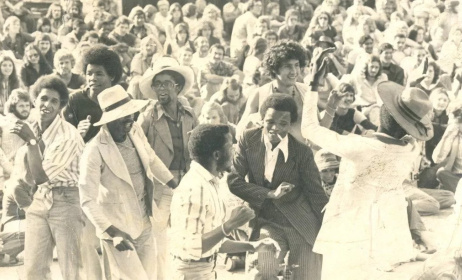

Out of this collaborative hub a musical entitled King Kong would open at the Witwatersrand University Great Hall in 1959. Not only bringing together multi-racial audiences for the first time in the country, King Kong, the story of the rise and fall of a township boxer, would go on to become an overseas sensation. Launching Miriam Makeba and many others’ international careers, the show also succeeded in sending several of its cast members into exile, including Makeba, Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, Caiphus Semenya and Letta Mbulu. They would soon become international ambassadors for the struggle against apartheid.

While King Kong was making waves around the world, a secretary for the Dock Workers Union of Port Elizabeth was causing a few ripples himself. Vuyisile Mini was a political activist who rose to prominence for composing a protest song while in prison awaiting charges of treason. The song, ‘Izakunyathel’iAfrica Verwoerd’ (Africa is Going to Trample On You, Verwoerd) was directly aimed at the Minister of Native Affairs, Hendrick Verwoerd, soon to become Prime Minister in 1958 and widely regarded as the architect of apartheid. It served as a warning, with lyrics such as:

Africa is going to trample on you, Verwoerd.

Verwoerd! Shoot…

You are going to get hurt.

Verwoerd, watch out.

Subsequently hung in 1964 for refusing to give evidence against fellow comrades, Mini was buried in a pauper’s grave. His legacy, however, lived on: his songs lit a fuse, paving the way for a new era of more direct, aggressive and mobilising protest music.

1970s: Uprising and a Direct Call to Action

The 1960s had been a quiet period of resistance in South Africa. The ANC had been banned and its leadership sent to Robben Island. For a time, protest lacked direction. Realising the danger of this leadership vacuum created by the government, musicians began to play an increasingly important role in communication. Meanwhile, on the island, senior political prisoners prohibited from mixing with other prisoners found a loophole in the form of choir practice. This was the only time when senior prisoners could be in the same space as those serving shorter sentences, some as little as six months. Through song, incoming prisoners would convey news from the mainland and in turn receive instructions.

A major turning point came on 16 June, 1976. Responding to the government’s latest racist decree forcing black students to be taught in the oppressor’s language, Afrikaans, the youth took to the streets. The Soweto Uprising was the embodiment of the highly charged political atmosphere of the time and marked the beginning of a more radical, militant phase of resistance. Again, music followed suit. The exiled ANC established its own cultural wing, the Amandla Cultural Ensemble, who protest songs were soon heard around the world. For example, ‘Sobashiya Abazali’ spoke of the youth leaving the country to receive military training under the newly formed armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK). They sung: “We will leave our parents behind and head for foreign lands in search of our freedom.”

For the first time, the youth had stood up and expressed their anger. There was no longer room for sentiment. It was the time for direct messages conveyed through song, or what could more aptly be described as a chant, known as toyi-toyi, with its energetic lifting of the knees to the waist replacing the peaceful marches that had marked resistance up until that point.

Introduced from those returning from training in Zimbabwe, toyi-toyi was a weapon of war, aimed at instilling fear and intimidation. It call-and-response chanting imitates the sound of firing guns and barking dogs – the sounds that marked this period of the struggle:

1980s: ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ and the Voëlvry Movement

After decades of oppressive rule, by the 1980s the apartheid government was beginning to feel both internal and external pressure. The tide was beginning to turn. Overseas, at the heart of this public outcry for an end to apartheid was a single call: “Free Nelson Mandela”. A band from Coventry in England, The Special AKA (also known as the Specials), were the unlikely group to lead the call with a song that combined upbeat pop with a serious political message. Their 1984 hit ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ sparked the momentum and soon a whole generation of youth around the world had gathered behind the movement to end apartheid. This pressure culminated on 11 June 1988, when over 600 million people in 67 countries around the world watched as performers paid tribute to Nelson Mandela on his 70th Birthday at Wembley Stadium in London. Considered by many to be a critical moment in finally bringing worldwide consciousness to the atrocities of apartheid, when The Special AKA performed ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ to the entire world, the South African government could do little else but listen. Other international musicians to bring South African culture and politics into the international spotlight include Peter Gabriel, Eddy Grant, Paul Simon and many others.

This newfound awareness of apartheid injustice was not only occurring internationally. Within South Africa, popular artists of all races were successfully beating the state’s complex censorship mechanisms to mobilise people to join the struggle against apartheid. Two of the most prominent acts in this regard were Stimela, who released politically relevant hits like ‘Whispers In the Deep’ (1986) and ‘Trouble In The Land Of Plenty’ (1989), and crossover artist Johnny Clegg, who emerged as an international star in the late 1980s. By the end of the decade, even popular ‘bubblegum’ acts began releasing outspoken political songs, such as Brenda Fassie’s ‘Black President’ and ‘Shoot Them Before They Grow’ in 1990.

At the same time, a group of Afrikaans musicians were also challenging the system and giving a new voice to the Afrikaner youth. They became known as the Voëlvry movement. Armed with the noble aim of emancipating Afrikaner youth from the structures of their authoritarian, patriarchal culture, musicians such as Koos Kombuis (André Letoit), Johannes Kerkorrel (Ralph Rabie) and Bernoldus Niemand (James Phillips) embarked on a countrywide campus tour to spread their message. Even the white, Afrikaans-speaking youth were finally joining the struggle. In later years, Letoit explained their reason for going against authority: “Because we had to. We knew there was kak in die land (trouble in the land) and we felt that our music just might make a difference.” Voëlvry showed how far protest music and the struggle had come – a far cry from the polite ‘grumblings’ heard amongst the church choirs of the Ohlange Institute.

Protest music in South Africa has always been a reflection of the times and changed over the years as the political situation evolved. It was also a tool to help shape people’s thoughts and attitudes that was used by musicians and political organisations both locally and abroad. By the end of the 1980s, there was no longer a part of the country that resistance had not reached. It had even spread to other parts of Africa and the rest of the world. Finally, the end was in sight - and music played a large part in getting there.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments