Hip-hop in Mali

By Simon Doniol

Today, hip-hop is the only music genre to fill up stadiums in Mali. Hip-hop culture has taken over the land of renowned musicians like the late Ali Farka Touré and Salif Keita. This comes as little surprise in a country where 60% of the population is under the age of 24 and therefore grew up listening to rap. Today countless independent production companies pop up regularly in Bamako and throughout the country, although home studios are largely improvised and there is no established structure that allows them to operate sustainably. The text provides an overview of this musical genre, its evolution, founders and current groups in Mali.

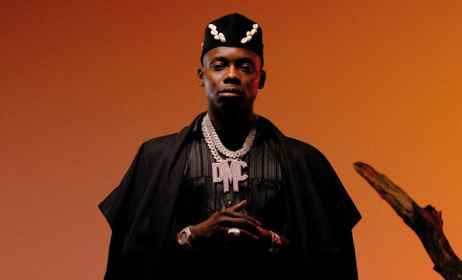

(Ph) Amkoullel © Maud Bernos

(Ph) Amkoullel © Maud Bernos

The rise of hip-hop in Mali

It is difficult to establish when the first rappers arrived in Bamako. As in Senegal, rap does not originate from the ghettos but rather from the upper-class families. In the 1980s, through their connections, Malian hip-hop fans would have imported VHS tapes of music videos from the USA or via relatives based in Europe. Local artist Amkoullel recalls: “I discovered rap with my brothers. At first I was beatboxing while they were rapping and emulating NWA, Public Enemy, and Grandmaster Flash. I did not understand English; the lyrics were translated for me later.”

Mali is no exception when the hip-hop movement swept through the world in the early 1990s. Amkoullel speaks of something very powerful: “It was very interesting to see young people do something, relate to music - especially in Mali, where only adults were represented on TV. There wasn’t really a platform for Malian youth to express itself.”

Hip-hop in Mali emerged alongside the arrival of democracy. The proliferation of private radio stations broadcasting this style of music contributed to its exponential growth. Television, however, remained the chosen media for most musician starting a career. Among the pioneers of Malian rappers, the group Sofa - composed of Lassy King Massassy (considered the father of all Malian rappers) and the late Master T - was the first group aired on ORTM in 1992. The group Mel Groove was also aired on TV, together with Alpha Touré featuring Rokia Traoré, but each member of the group soon left to pursue other interests.

Amkoullel recalls the early days and the challenges with making rap music acceptable to the Malian audience: "At first it was complicated, we were accused of imitating the Americans or Europeans and rap wasn’t a culture in Mali. They were not completely wrong. Malian hip-hop eventually evolved using our own cultural values and heritage in Bambara and other national languages. It took us 10 years, but people finally realized that hip-hop was there to convey a message.”

This is especially true in a country where oral tradition is an art that was traditionally reserved for the griots, and public speaking is not open to everyone. "You are expected to convey a consistent message or else nobody listens,” adds Amkoullel.

Morality in Malian hip-hop

Are rappers the modern griots? “In a nutshell,” agrees Amkoullel. “Like the griots, we are storytellers, we are here to remind our brothers and sisters who we are by drawing attention to issues relating to our identity, our principles, and our values. Today the modern griot sings praises to anyone, even if the person has diverted public funds and it is common knowledge. It has become more of a business relationship, even though some have safeguarded their integrity.

“The ancestor of the rapper is rather the bolon player,” suggests Amkoullel. The bolon player was the only member allowed to speak and criticize openly in the king's court. This is a right that resonates with another famous rap group in Mali, Tata Pound, who released popular songs like ‘Cikan’ (2002), which took then-President Amadou Toumani Touré to a task, as well as ‘Monsieur le Maire‘ in 2006. The song was later subjected to censorship. “Tata Pound is the Malian equivalent of Public Enemy” explains Amkoullel.

Malian hip-hop typically addresses themes (excluding current clashes between famous artists) focused on unemployment, health, education, family values, money, political accountability, and corruption. The singer or group represents his grin - a place where men, and now women, of the same age gather and share their views freely. Moreover, Malian rappers willingly accept their moralizing character, delivering ‘conscious’ speeches aimed at being the voice of the voiceless (Schultz, 2012).

Amkoullel elaborates: “Here in the United States when you say you rap, most people expect you to talk about girls, bling, money, gangstas or violence. Whereas in Mali and West Africa in general, when you say ‘I am a rapper,’ people will not necessarily have this image”.

In a country where almost 70 % of the population is illiterate, word of mouth remains the best way to reach the masses. The political crisis of 2012 and the war in Mali saw the mobilization of Malian artists. Rappers were first in line to challenge, inform and come up with solutions. “When the President bought a plane, there were rap lyrics against it. When the MNLA tried to claim that it represented the Tuareg of Mali, which is a big lie, we put things in perspective through our lyrics,” says Amkoullel.

Key figures and ongoing challenges

Today, the rap scene in Mali, although very active, does not have the necessary infrastructure to ensure and maintain its development. Productions houses like Papy Kroniks Music, Sidiki Diabaté, Luka productions, Maliba productions (audio and video), Doc Bah Fansé 8.8 (video), Dark Face Films (video) or L-Pacifico are among the most active in the market. Rappers like Iba one, Tal B, Gaspi, Mylmo, Master Soumy, SMOD, Mobjack, Cosby and Amy Yerewolo take center stage. Websites such as Rhhm.net and Badama City post information on the latest releases, while ‘the Mali Rap show’ on TM2 remains a popular forum for young talent.

However, the state, through the Malian Copyright Office (BuMDA - Bureau Malien des Droits d’Auteurs), is not doing its job. A lack of transparency makes it virtually impossible for a musician to live from their art. Private organizations such as Orange offer some opportunities during promotional tours by offering a contract spanning two to three years, but its monopoly makes it difficult for other initiatives.

It is also difficult for a rapper to tour outside of the country. Amkoullel adds: "Ironically, it is much easier for a Malian artist to tour Europe or the United States than the African continent. The production quality is good, the talent is there. But it's the business side and all the administration that doesn’t follow".

Sources:- Amkoullel - personal interview in Paris / Washington. 2015.

- Amkoullel, the Fula child. 2014. ‘Malian Hip Hop: Social engagement through Music’. In Wakati, Ni Hip Hop and Social Change in Africa. Lexington Books.

- Badama-city.com: http://www.bamada-city.com

- Diakon, Birama. 2009. ‘Youth and Rap in Mali (an introduction)’. http://fr.netlog.com/diakonbirama/blog/blogid=3701388#blog

- Juompan-Yakam, Clarisse. 2013. ‘In the footsteps of Ramsès Darafida, leader of Tata Pound’. Jeune Afrique: http://www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/JA2718p139.xml0/afrique-mali-musique-bamakomali-sur-les-pas-de-rams-s-damarifa-leader-de-tata-pound.html

- Kwal. 2008. ‘Rap in Mali’. Respect Mag: http://www.respectmag.com/rap-au-mali

- Maxwell, Heather. 2012. ‘Malian Music Prevails in Troubled Times: Rap / Hip Hop Music and Festivals Rally to Rebuild the Nation’. Voice of America: http://blogs.voanews.com/music-time-in-africa/2012/08/30/malian-music-prevails-in-troubled-times-rap-music-and-festivals-rally-to-rebuild-the-nation/

- Minimum, Benjamin. 2012. ‘Amkoullel, a Malian rapper in the heart of the protest’. Mondomix: http://www.mondomix.com/news/amkoullel-un-rappeur-malien-au-coeur-de-la-protestation

- Morgan, Andy. 2014. ‘The Voice of the Voiceless: An In-Depth Portrait of Mali's Hip Hop Scene’. http://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/magazine/mali-rap-feature

- Rhhm.net: http://www.rhhm.net

- Schulz, Dorothea. 2012. ‘Mapping cosmopolitan identities. Male Rap Music and Youth Culture in Mali’. In Africa Hip Hop: New African Music in a Globalizing World. Indiana University Press. https://www.academia.edu/9228463/Mapping_cosmopolitan_identities._Rap_Music_and_Male_Youth_Culture_in_Mali

- Traoré, Kassim. 2014. ‘Mali: Amkoullel-Djiguitigueba or the great disappointment. A single to denounce the current government’. Maliactu.net: http://maliactu.net/mali-amkoullel-djiguitigueba-ou-la-grande-deception-un-single-pour-denoncer-la-gouvernance-actuelle

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments