Best of 2017: Ogene: How an Igbo genre broke into mainstream Nigerian music

This story was first published on 13 April 2017.

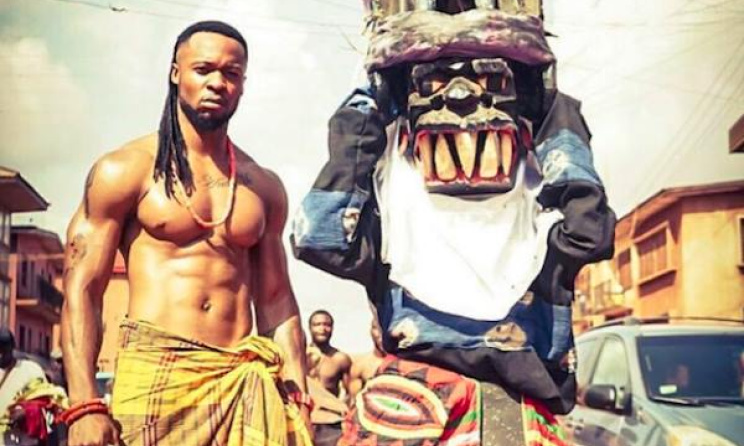

Flavour on set for the Gbo Gan Gbom music video.

Flavour on set for the Gbo Gan Gbom music video.

Sometime last year my cousin and I decided to unwind at Villa Toscana, a hotel/nightclub with an open bar located in the heart of Enugu.

Driving into the spot, we noticed the place was packed. The reason for the turnout, we later discovered, was the presence of the in-house ogene band that performs every other Sunday. This was proof ogene music was coming into its own.

The atmosphere encouraged bad behaviour, and soon enough some guy a table away from where we sat drew a Beretta from its holster, firing two shots in the air. No one seemed to mind. As is often said in these parts: ogene and rascality go hand in hand.

Drinks poured and gulped, we began to lose ourselves to the magical sound of the gods. Yes, ogene (the metal gong) – or agogo as the Yorubas call it – has been associated with the Igbo masquerade cult since the time of our ancestors. Its history, as far as is known in south-eastern Nigeria, can be traced to Achi in Enugu State and Awka in Anambra State. While it is often a cause of heated debate, it is not clear if lyrically Ogene Mpkakija, an Anambra sound, preceded Ogene Okponma, its Enugu variant, although it is incontestable that the latter city has nurtured it the most, integrating the sound into both urban and rural Enugu culture.

As an instrument, ogene is forged by blacksmiths who can still be found in Awka. It is the most important of an array of Igbo musical instruments including the ekwe, igba, oja, udu and ichaka. Besides the town-crier’s use of the instrument, it is needed at cultural events, not to mention rituals. To play ogene music, only two instruments are vital: the lead ogene itself and the oja (flute). These days, however, the music has evolved so much that it is normal to find an ensemble of all the instruments listed above. Even so, ogene music is nothing without the message it transmits.

The message, amplified by the often husky voice of a male lead singer clutching an ogene, tells all kinds of mundane stories about life – from the personal to the sexual to the communal – by deploying a densely metaphoric and idiomatic language. Dictating both the tempo and rhythm of the sound, the lead calls and backups respond in ways that engage an audience in conversation, so that if he decides to sing your praise, you are almost compelled to nod, dance or part with some cash.

This is the nature of the sound that went commercial in the early 1970s seizing the heart of Coal City. This is a form of music made popular by artisans and roughnecks.

It is said that in Enugu, the sound was first carried from Coal Camp by a group called 007, which was made up of the young residents of the neighbourhood. It then spread to areas like Obiagu, Ogui, Asata and Uwani. Pushed further by groups such as Emesibe, Ogui boys and Coal City boys in the 1980s, the sound caught the attention of Chief Mike Ajaegbo, owner of the then popular Minaj Broadcasting International. Ajaegbo promoted the sound by organising an annual ogene music competition in Obosi, Anambra State, in the 1990s. It was at an edition of this competition that Shidordo, perhaps the most versatile ogene musician, was discovered.

Having profited from Ajaegbo’s platform, Shidodo took ogene to Germany in the 2000s, thereby becoming ogene's biggest exponent. In one song he narrates an experience at an embassy in Germany where he had to sample the ogene sound. Ogene music birthed other prodigies in the 1990s, notably Igbo Ja and Kalu Uma, who took the sound beyond Enugu. Unfortunately, for the most part these artists have to depend on a burial, traditional wedding or chieftaincy ceremony.

To enjoy ogene, one doesn't only listen to the music; you watch a performance, as the sound lends itself to drama and robust dance. A typical ogene performance is atilogwu without calisthenics. And today, in a little diluted form, it has passed into mainstream Nigerian music – thanks to songs like Zoro's ‘Ogene’, ‘Achikolo’ and Flavour's ‘Gbo Gan Gbom’. And, truth be told, the sound has paid its dues with sweat, grime and blood. It belongs mostly to the age-grade of those who lead masquerades, and as anyone familiar with the sound will readily tell you, ogene is music that thrives on brawls.

Heralded by local musicians such as Shidodo, Igbo Ja and Kalu Uma, the ogene sound is finding its way into urban Nigerian music, with the release of Zoro’s ‘Ogene’. The rapper asks on the songs: "Have you heard the sound of ogene?" He adds boastingly: "We are fusing rap into ogene. You know what I mean?" It seems, to Zoro at least, that only through a fusion of rap and ogene could the sound have swum to the mainstream. In many ways the song is a sort of announcement: not only demanding that we hear the sound, Zoro says he is the first to dish it out big time. This is probably why he says: "Bring your sickest rapper, sum it up, bitch a bu m the total." If he has brought this regional sound to the country, then he is better than the sum of any collection of rappers.

Zoro hails from Awgu in Enugu State, a local government area bounded in the north by the Udi and Nkanu West local government areas. So it is not difficult to see why he is the perfect act to sing ‘Achikolo’, a song in which he gives his Igbo colleagues Phyno and Flavour shout-outs. It is also where he acknowledges Pammy Udubunch, a group that came onto to local scene in the 2000s, even as their sound is more igba than ogene. No surprise then that the trio of Zoro, Phyno and Flavour would come together to make ‘Gbo Gan Gbom’, a mainstream song closest to the sound of raw ogene music. To be sure, the song title has no meaning beyond the 'actual' sound of ogene.

The song gets its effect, at least to the Igbo speaker, from putting into words all that ogene represents. Expressed in and enriched by a dialect that best carries its message, 'Gbon Gan Gbom' vividly projects the sexual and violent undertone of the ogene sound: from Flavour promising to kill a goat for a fair lady if she puts her heart into a dance to Phyno threatening to split open what can only be another guy’s skull if he dares touch him, right before asking how much yam the fellow has eaten.

All three artists grew up in Enugu. And it is instructive that like town-criers, in announcing their decision to set out on a journey, they convey the message through the medium of ogene. These lads do not just hand their listeners a map, they point out the target, the place they seek to position the sound: mainstream Nigerian music. The trio seem to be sending out a message of encouragement to lads like those who make up the in-house Villa Toscana band, saying: If you work hard at your craft you can do more with this sound.

Anyi ji aka, ku b’akana.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments