Can 'Afrobeats' do what Afrobeat did?

By Ettobe David Meres

On 28 April 1989, the headline categories at the Nigerian Music Award Night were Best Highlife, Best Juju, Best Traditional Music, Best Reggae, Best Afro and Best Pop.

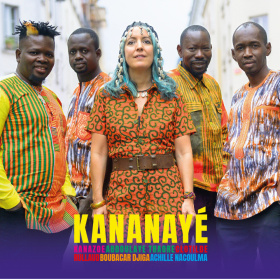

Fela transformed highlife. Can 'afrobeats' do same?

Fela transformed highlife. Can 'afrobeats' do same?

Perhaps the different categories signalled newly found eclectic tastes in the market. Perhaps it was because the number and quality of professional Nigerian musicians had increased. But it is undeniable that for the organisers and for those interested in the taxonomy of Nigerian music these were straightforward classifications.

Highlife: check for some melodic melancholy. Juju: check for enabling energetic dancing. Traditional music: check for indigenous sounds yet to earn their own genre. Reggae: check for Bob Marley. Afro and pop: well, check for Africa and for America.

Of these popular Nigerian music genres, highlife is unique. It is international—having originated from Ghana— and it is usually sung in English interspersed with local languages. It is also found in most West African countries. Juju musicians like Ebenezer Obey and traditional musicians such as Dan Maraya Jos could easily be identified with their local audiences; that is, as Yoruba and Hausa music. Though their songs are mostly sung in Nigerian languages, these musicians lacked national conquistadorial ambitions. In contrast to juju and traditional musicians, contemporary Nigerian musicians are much keener on national and/or continental conquest, whether they are singing in English or in Nigerian languages. That’s why Flavour’s chorus on MI Abaga’s song 'Number One' boasts: "African rapper number one o/ MI you microphone magician." It is also why rapping in Yoruba won’t stop Olamide from declaring he is the "baddest guy ever liveth".

Decades later, the contemporary Nigerian music scene is suffering from a condition similar to the 1960s when many artists aspired to play music in the lucrative highlife genre. More than ever before, contemporary Nigerian musicians are sharing the stage, some acclaim and maybe money too with Western superstars. But to be commercially viable in Nigeria, contemporary Nigerian musicians have 'learnt' to sound alike.

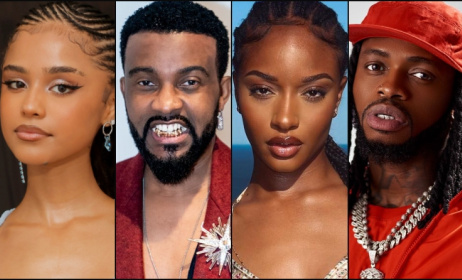

It is easy to differentiate between early Tiwa Savage and her peers; not so easy to differentiate between Mavin's Tiwa Savage and her colleagues. There is one dominant sound, rhythm, beat, stifling all others. The conclusion one draws is this: the contemporary Nigerian sound is a victim of its own success.

A controversial consequence is that instead of bothering to appreciate the nuances of a genre or style, there is a tendency to lump them all together. There might have been less of a controversy if this 'lumping' was done under a name like Contemporary Nigerian Music or something less unwieldy, but it is the lazy 'Afrobeats' that have been picked, mostly by Western media.

The Headies, which started in 2006, and the now defunct Nigerian Music Award of 1989, have both been referred to as Nigeria’s versions of the Grammys, an aspirational description at best. The main award categories at the Headies are usually Song of the Year, Best Rap Album, Best R&B/Pop Album, Best Rap Single, Best Pop Single, Best Street-Hop Artiste, and Best Vocal (Male and Female). Barring a tinge of influence here and there, it can be argued that none of the winners in 1989 sounded like each other. Indeed, the acoustic dissimilarities obtainable in 1989 can be gleaned from the nominal variety in award titles.

Don Jazzy and DJ Jimmy Jatt can rail all they like about how unfair it is to lump Patoranking with Dr Sid as 'Afrobeats'. And about how different they sound compared to Fela, the originator of Afrobeat. But it wouldn’t matter if they don’t do to their individual sounds what Fela did to highlife and jazz.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments