Who gains from Kenya’s dysfunctional music royalty space?

When the Kenya Copyright Amendment Bill of 2019 was signed into law, it was seen as a new dawn for creatives. In particular, it changed the legal conceptualisation of copyright and related rights, and empowered the Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO) to be directly involved in the governance and management of revenue collection in the music industry while playing a regulatory role.

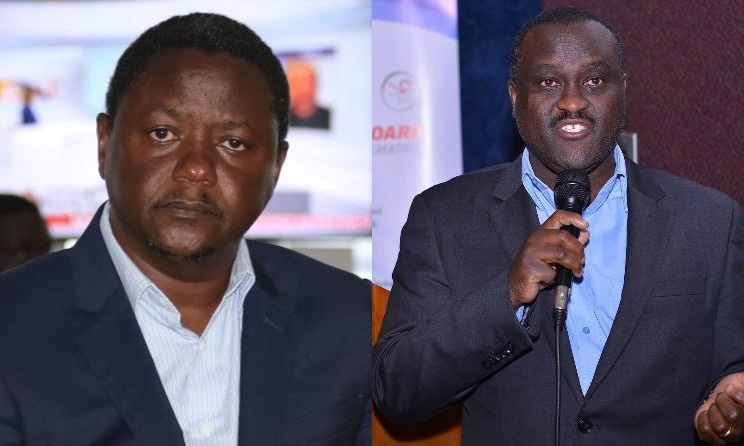

KECOBO’s Mutuma Mathiu and Edward Sigei admit that ‘the management of copyright in Kenya is a mess’.

KECOBO’s Mutuma Mathiu and Edward Sigei admit that ‘the management of copyright in Kenya is a mess’.

The amendments to the bill were based on guidelines drawn up by Kenya’s licensed collective management organisations (CMOs) – namely the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK), the Kenya Association of Music Producers (KAMP) and the Performance Rights Society of Kenya (PRISK). Proper management, transparency and goodwill were necessary for the new legislation to function as envisaged.

Two years later and the optimism that attended the signing of the bill has dwindled, with creators at loggerheads with the CMOs as well as KECOBO’s management practices and regulation of the royalty space.

A long tug of war

Based on the amendments introduced in sections 46 and 49 of the Copyright Act, KECOBO was empowered to delve into the day-to-day operations of the three CMOs, effectively micromanaging their operations. The CMOs issue licences to users of copyrighted works – like broadcasters, live music venues and places of entertainment – to play music as part of their services.

Since the establishment of Kenya’s first CMO, the MCSK, in 1983 until today, rights holders and users alike have publicly voiced concerns about corruption, mismanagement, aggressive licensing tactics and lack of transparency on the part of CMOs. Based on these concerns, the KECOBO board commissioned a forensic audit in 2020, which found the three CMOs at serious risk of misappropriation of funds, civil and criminal liability, and loss of income from penalties and sanctions. KECOBO resolved to submit the audit report to the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) to investigate suspected fraudulent transactions at the CMOs. The DCI has completed the investigations and the matter is now with the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions and the judiciary.

In 2018, KECOBO refused to renew the MCSK’s licence in favour of a new player called the Music Publishers Association of Kenya (MPAKE). The MCSK went to the High Court, which ruled the decision to award MPAKE a CMO licence as unlawful. After that debacle, the MCSK was reissued its licence and is currently collecting royalties on behalf of its members. Back to 2020 and KECOBO revoked MCSK’s licence for a second time and denied it access to the royalties that it had collected in a bank account monitored by the regulator. CMO licences in Kenya are issued annually and are valid until 31 December.

In August this year, the KECOBO board deregistered all three CMOs, which were operating with provisional licences that were issued in late 2020 and expired in May 2021, citing noncompliance of licensing conditions, specifically the breach of administrative cost limits and the diversion of royalties into an undeclared account. The CMOs were also accused of breaching administrative cost limits by distributing only 35.9% of Ksh114m ($1m), with the remainder going towards administrative and operational costs. But the High Court Constitutional and Human Rights Division suspended the decision later that month, allowing the CMOs to collect royalties until 3 November, when the court will hear a similar matter in a case filed by KECOBO on 14 July. The regulator is now seeking an order to freeze the bank accounts in which jointly collected royalties are being held, and effectively aiming to halt the CMOs’ operations. It also wants to collect and distribute royalties to rights holders or assign an agent to do so. KECOBO expects CMOs to distribute 70% of collections and spend 30% of those on administrative costs.

A statement released on 2 August by the MCSK implies that its strenuous relationship with KECOBO has resulted in uncertain future operations – negatively affecting its relationship with partners like the World Intellectual Property Organization, which had expressed interest in the past to invest in the CMO and provide it with support to improve its documentation, distribution, monitoring and licensing systems.

Conflict of interest

The current chairman of KECOBO’s board is Nation Media Group (NMG) editorial director Mutuma Mathiu. NMG is an independent media house that publishes and distributes printed newspapers and magazines. It runs radio and TV stations in East and Central Africa.

Since his appointment as KECOBO chairman by President Uhuru Kenyatta in 2019, Mathiu’s actions have favoured broadcasters and content service providers (CSPs) that do not comply with royalty payments to rights holders through the licensed CMOs. CSPs are required by law to obtain a copyright licence from the CMOs to exploit copyrighted musical works of their members, particularly public rights and mechanical reproduction rights. However, CSPs can deal with rights owners if they have struck direct deals with them, which is another bone of contention between the warring parties.

In January 2020, during an address to the nation in Mombasa, Kenyatta directed the Ministry of ICT, Innovation and Youth Affairs to “eliminate” CSPs that work with digital platforms. “Regarding CSPs, I intend to support the sector using a multi-pronged approach,” Kenyatta said. “CSPs who work with digital platforms such as SKIZA and Viusasa will be eliminated. And this is because they sit outside the CMOs.”

In 2020, a year after Mathiu was ordained as KECOBO chairman, controversial joint broadcast tariffs were gazetted at low flat rates, resulting in further loss of revenue from royalties. Best international practice, as provided by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC), says that tariff rates should be commensurate with the annual revenue broadcasters earn from the copyrighted works they exploit, subject to a minimum monthly fee.

Even with the low flat rates, most broadcasters, including the state-run Kenya Broadcasting Corporation, still owe royalties to the CMOs worth millions of Kenyan shillings. Despite this, media regulator the Communication Authority of Kenya, continues to issue non-compliant broadcasters with licences.

The credibility of Liberty Afrika Technologies

In April 2020, the heads of Kenya’s CMOs – Japheth Kassanga (MCSK), Anthony Karani (KAMP) and Ephantus Wahome (PRISK) – signed an agreement for the implementation of an ICT system through Liberty Afrika Technologies, a CSP producing content for the SKIZA ringback tone platform, which is owned by telecommunications giant Safaricom. The company also lends to individuals, including musicians, through its three short-term loan advance products accessible via USSD.

According to MCSK’s 2 August statement, Liberty Afrika Technologies’ system is still under construction and is unable to effectively monitor music usage or the distribution of royalties. KECOBO is also asking the CMOs to pay a monthly commission of 2% of all royalties collected – of which 1% is meant to offset the balance of the cost of the system (Ksh85m) while the 1% is earmarked for maintenance.

“The CMOs being compelled to pay for the licensing system is contrary to assurances given in a meeting on 20 December 2020 to the CMOs chairmen and CEOs by Hon. Joseph Mucheru, Cabinet Secretary of ICT, Youth and Innovation, that the government had sourced for a sponsor to procure the system for the CMOs so that they do not have to dig into royalties collected,” the MCSK said.

Liberty Afrika Technologies’ tender has raised questions about the procurement processes at KECOBO. It appears that KECOBO’s leadership did not conduct due diligence on the company before awarding it with the contract. Liberty Afrika Technologies CEO Sidney Ngunyi Wachira also owns Goldrock Capital and is a director of Webmasters Africa – the two companies behind the collection and mysterious disappearance of Ksh5.6bn of government funds through eCitizen, an online portal that provides essential services such as applications for passports, driving licences, business registration certificates, vehicle logbooks and title deeds. Kenyans were unaware that that money had been collected in an M-Pesa account set up by the two companies.

There have also been several complaints from rights holders regarding accountability and transparency about how Liberty Afrika Technologies and Xpedia Management, another CSP owned by Wachira, distribute royalties from SKIZA.

For instance, gospel artist Peace Mulu told The Standard newspaper in 2015 that she was cajoled into signing off the rights and ownership of her music to Liberty Afrika. Muli, who had just been discharged from hospital, was approached by a Liberty Africa representative who offered to help settle her medical bill of about Ksh1m by paying her Ksh150 000 per song subject to her signing an agreement. Unknowingly, she signed off the rights and ownership of the songs to Liberty Afrika. “I was desperate,” Mulu said. “They told me they could promote my songs for one year and gave me Ksh400 000.”

But according to The Standard report, Mulu had signed away the ownership of the songs to the company for five years in an agreement that would be renewed automatically unless either party issued a one-year prior notice of intention. Liberty Afrika Technologies proceeded to upload the songs on SKIZA, and from March to May 2016 made more than Ksh1.7m off the music. Data indicates that about Ksh29 000 was transferred to Mulu after the deduction of fees. Then, from July 2015 to February 2016, Ksh4.6m was paid out to Liberty Afrika while only about Ksh13 500 went directly into Mulu’s bank account.

“There is completely no transparency. We are living in shanties in Kangemi [a Nairobi slum] while people are eating on our money pretending they are assisting us to sell our music,” Mulu told The Standard. In January 2017, Liberty Africa Technologies asked Mulu to sign an affidavit, after which she received a sum of about Ksh372 000 and the matter was closed.

Music In Africa has not been able to view the original agreement between Mulu and Liberty Afrika Technologies and cannot confirm its contents, but a source close to developments in Kenya’s royalty space, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the CMOs had previously called out KECOBO for the manner in which it seemed unperturbed by how CSPs exploited musicians when in dire need or due to inexperience in matters of intellectual property rights.

Apart from the aforementioned companies, there are more than 60 CSPs currently exploiting musical works in Kenya.

Tariff windfall for broadcasters

Broadcasters are the biggest users of copyrighted works in Kenya, yet they are now subject to the lowest tariffs in recent years.

“How the revised broadcast tariffs were negotiated raises serious questions about the credibility of those involved in decision making at KECOBO,” the source said. “It is common practice that the price of goods and services is dictated by the country’s market forces, inflation and economic status. These are parameters that should have been considered while negotiating for the tariffs.

“What happened was that the CMOs had proposed tariffs that they presented to KECOBO, which was then meant to forward it to the Attorney General [AG] for publishing in accordance to Section 46A of the Copyright Act. But what happened was that KECOBO said the tariffs were too high and went on to renegotiate for a flat tariff, which was presented to the AG.

“KECOBO’s interference with the operations of the CMOs has reduced them to be sort of like a quasi-government department of KECOBO. Broadcasters do not go to the Communication Authority of Kenya to discuss their rates. Landlords do not go to the Ministry of Transport, Infrastructure Housing, Urban Development and Public Works to discuss how much rent they should charge tenants. So why should it be different with copyrighted works, which is private property according to the Kenyan Constitution?”

The KECOBO board released a statement on 28 July in which it admitted that “the management of copyright in Kenya is a mess”. For many players in the Kenyan music industry, the impasse between KECOBO and Kenya’s CMOs cannot be tolerated much longer. Many music professionals are calling for the formation of a registered and well-funded music trade union that represents the rights and needs of musicians and creators. They are also calling for the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission to step in to ascertain the extent of corrupt activities taking place between KECOBO, the CMOs and connected individuals in the private sector. But for now, it seems like it will be business as usual in a space that could make the difference between hunger and prosperity for music practitioners in Kenya.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments