Hip hop in Sudan

At the start of the 1960s, Sudanese musicians began incorporating Western influences in their compositions. Brass instruments, accordions, electric guitars, violins, synths and pianos, accentuated by drum kits, produced a hybrid sound of jazz and blues that was widely loved.

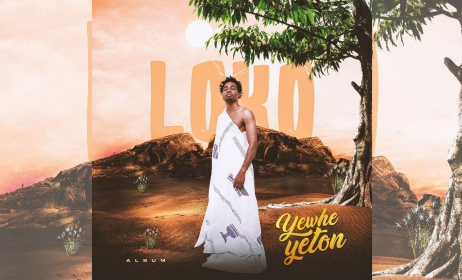

Sudanese rapper Gadoora.

Sudanese rapper Gadoora.

Coinciding with the global youth movements of the time, ranging from the anti-colonial struggle to post-independence instability, the youth embraced the music and went on to influence the socio-political sphere.

Also referred to as the ‘Golden Era’, this period produced a number of legendary singers such as Mohammed Wardi. However, the imposition of sharia law in 1983 dealt a blow to the creative industry, but against all odds, another generation of young people started embracing the music of the time – hip hop [1].

This overview text explores the history and current state of hip hop music in Sudan.

Beginnings

Due to Sudan’s long history of political instability and Islamic censorship, limited hip hop activity took place until the late 1990s. Banned in 2004 by the authorities for being political, pioneering hip hop group, Nas Jota, fled the country. This would later help create a vibrant diasporic Sudanese hip hop community scattered across the world, mainly in the Middle East and the US [2].

Likewise, back in Sudan, there was a growing hip hop community with an active scene before the 2011 South Sudanese independence referendum. There was a weekly open mic show at Papa Costa Restaurant in the capital Khartoum between 2007 and 2009, with cultural organisations such as the British Council and Goethe-Institut also giving rappers like Abdulgader Yasir, aka Gadoora, a platform.

A British Council project titled Words and Pictures (WAPI), in partnership with the Ministry of Culture and Goethe-Institut, brought together several upcoming artists from across the country to stage small, weekly concerts in Khartoum [3]. During that period, the country was at war, as the southern part, predominantly black and Christian, waged war against the Khartoum government, predominantly Arab and Muslim, over discrimination and segregation.

In 2010, as the country geared up for a referendum to determine the independence of the south, Nas Jota released an album titled Sudan Votes Music Hopes, which is arguably Sudan’s first major hip hop recording.

Nas Jota followed up the release with a song titled ‘La Dictatorship’, which was further amplified by United Arab Emirates-based rapper Moawia Ahmed Khalid. In response, the Omar al-Bashir government banned their songs and targeted their Sudan-based protégés [4].

In the southern part, rappers discovered by the WAPI project, such as Geng Dulwa and Emmanuel Jal, as well as several others who were dispersed by the war, found their creative abilities living in exile and in refugee camps [5].

The government’s high-handedness was only amplified following the secession of the south, which gave rappers like Emmanuel Jal a new nationality.

Impact of the Arab Spring

As a wave of youth-led protests swept across the Arab world in 2011, Arabic hip hop became a major driving force for political change. Young people in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Libya and Syria, among other Arab countries, capitalised on the sudden freedom to express their discontent towards authoritarian governments while highlighting social and political imbalances. The youth were now speaking bluntly and weaving revolutionary and intellectual content in their lyrics while speaking truth to power.

There was a proliferation of home-made music videos and songs from the Arab world, thanks to digital tools and social media, which greatly popularised hip hop as the voice of the youth [6].

In Sudan, the government maintained its decades-long control over the airwaves as rappers became critical voices, both locally and in the diaspora, after finding an audience on social media and streaming platforms like ReverbNation and Audiomack. US-based acts like Oddisee and Nas Jota as well as home talents TooDope and Flippter were increasingly leading the way in using social media to get their message across. In 2018, diasporic acts such as Nas Jota and Ayman Mao picked lessons from the Arab Spring and encouraged protesters to overwhelm the al-Bashir government. After the military overthrew the dictator in 2019, several artists in the diaspora returned home to hold concerts [7].

Hip hop today

Despite the growing acceptance of hip hop among the youth, the is still a negative public perception of the genre due to Sudan’s conservative leanings. However, this has presented an opportunity for artists to use their music to convey messages that address themes like peace, love, freedom, hope, unemployment and women’s rights.

Hip hop has also made a bigger appearance on Sudanese media, with a growing number TV and radio stations aligning themselves with younger demographics and incorporating hip hop as part of their programming. Radio stations such as Capital 91.6 FM, Vision 103 FM and Pro 106.6 FM are some of the leading supporters of hip hop in Sudan.

The rap scene in Sudan is currently witnessing an explosion of sorts, as more and more rappers use the accessibility of home production tools and tech to their advantage. Among the younger generation of rappers are the likes of Ahmed Bushara, Mohab Kabashi, Elkhalifa, Omar Dafencii, Hleem Taj Alser, Moe the Poet, Bani Jr, Buddha and Mandela.

Resources and citations

[1] https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/best-sudanese-rappers

[2] https://tinyurl.com/5n8hcbbx

[3] https://playbookbeta.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/wapi.pdf

[4] https://books.google.de/books?id=6mR2DwAAQBAJ&printsec

[5] https://www.andariya.com/post/The-Influence-of-Hip-Hop-in-South-Sudan

[6] https://hir.harvard.edu/rap-and-revolution-from-the-arab-spring-to-isil-and-beyond

[7] https://www.voanews.com/a/arts-culture_banned-sudanese-musicians-celebrate-new-year-new-sudan/6182273.html

Disclaimer: Music In Africa's Overviews provide broad information about the music scenes in African countries. Music In Africa acknowledges that the information in some of these texts could become outdated with time. If you would like to provide updated information or corrections to any of our Overview texts, please contact us at info@musicinafrica.net.

Editing by Peter Choge and Kalin Pashaliev

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments