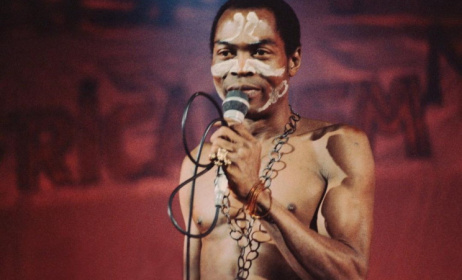

The strange confessions of Fela's last manager

It could have been very different. Rather than that substantial, smoking toke poking through his fingers, it could well have been things less subversive: candy, pastry.

Rikki Stein managed Fela from 1983 until his death in 1997.

Rikki Stein managed Fela from 1983 until his death in 1997.

All this means is that besides music, women and weed, I can reveal to you that Fela’s other great loves were acid drops—sour-sweet candy popular in England—and Swiss rolls. So great was this love that his manager, Rikki Stein, travelling from England to Nigeria, would raid the factory for cases and cases of acid drops, and sweep Swiss rolls clean from the shelves of dozens of grocery stores. And even if Fela was kind and generous with everything, including his beloved women, those acid drops and Swiss rolls, he did not share.

Stein had called me “smartypants” in a Twitter DM out of the blue. He would catch me off-guard once more as we talked. “How do you mean? What does that have to do with anything?” he sneered when I asked him where he found the energy to get up and go at 75.

That little passive-aggressive episode was not without reason. For people who completely immerse themselves in the great loves of their lives, it can be difficult to contemplate separation.

“I’m a rocker and a roller,” said Stein, whose wizened face and head of white hair call to mind Arsene Wenger, the outgone Arsenal manager who expressed similar sentiments about football. “I guess it’s the music that gives me the energy to do what I do. Just as well because managing music is such a stupid job, man, which if you did not love you could not do. I’m not gonna retire. I will stop when I drop. Sit down and do what? Watch telly?”

These days Stein is backing Okaymusic, a platform he insists can help artists here, solid in their own territory, find a wider, more diverse audience. “It’s been happening for years,” he says. “You tell them nobody knows them but they don’t want to hear it. They say they go to London to perform but who do you play for, man? Your people are happy to see you but the rest of the population is oblivious to you. In the past, it used to be Sunny Ade playing huge sold out venues. He’d collect a shitload of money and go home and nobody would know he’d come around except for the people who were there. It’s changing now but there’s still a lot to do.”

Before he was 15, Stein had set up a jazz club where, once a week, he’d pay jazz musicians—top names, he claimed—£5 to perform. Then he brought English rock and roll bands into Europe. Soon, he was managing the Moody Blues, whose lead singer had left to join Paul McCartney’s Wings. “They [the Moody Blues] were distraught and came to live with me in this little town on the French border. They were popular in France and it wouldn’t be hard to find them gigs. One day, this Jaguar drove into the town square and a guy gave them £10 000, which is like £100 000 today, to buy new gear and everything. And they jumped in this Jaguar and drove away.”

Then came Fela, whom Stein managed alongside the Ballet Africaine, Guinea’s national troupe.

Stein’s first encounter with Fela had something of the divine to it, a secular Damascene encounter. How much of it is mythmaking no one knows, but across several interviews Stein repeats the same lines verbatim, a truly confounding capability. Citing the appropriate highlights—Mercedes van, M4, sorrow, tears and blood—I summarised the myth and got to the point.

Q: Was this a businessman’s nose for business or did you sense a kindred spirit?

A: I had no thoughts about business. I was organising a Rain Forest festival and I wanted to invite artists from all the rainforest countries to come together, not just to play music but also to discuss.

Q: Which musician have you worked with whose personality has approached Fela’s?

A: Rasheed Taha, an exceptional Algerian who lives in France. I met him the same year I met Fela. He was exceptional, with the same integrity.

Q: Your relationship with Francis Kertekian has always fascinated me…

A: When somebody like me turns up and you’re a manager, you go like, 'What the fuck?' And that’s exactly what happened. We became friends and it was a friendship that endured for 25 years. He was a great guy.

Q: You both brokered a deal with Universal for about a million dollars after his death. But there was this thing with Motown in the late 1980s, which was going to be about a million dollars as well...

A: More than a million dollars.

Q: You can’t be very fond of Professor Hindu right now.

A: I love Professor Hindu.

Q: You love him? But he lost you guys a great deal of money.

A: No. That’s bullshit, bullcrap. It’s just the way he became a scapegoat for this thing, you know?

Q: I mean the Motown deal.

A: How did he scupper that?

Q: Well, at some point, Hindu was Fela’s go-to guy. If he said no, that was it.

A: He didn’t say no. I spent 10 years digitally remastering Fela’s catalogue. A lot of it was recorded under very primitive conditions and we needed to get rid of every click and clack, without touching the music. We could do about 10 minutes a day. I mean it’s forensic business, man. You go right in there with tweezers and pull them out.

In the middle of that job, we went to Midem [music industry conference] and we met with Timmy Regisford because Motown wanted to start an African label. They heard some of the stuff that we finished and they were like, 'Whoa!'. Timmy Register came to Lagos to meet Fela, and Fela wasn’t very good with record companies, you know. So he didn’t give the guy an awful lot of time. But while he was here, he signed Femi to Taboo and they went to New York to do a recording. They wanted a five-album deal with Fela, a quarter of a million dollars per record, plus $50 000 a record, tour support, plus publishing, and they wanted to buy the catalogue for a million dollars, which all made up for like a $3m deal, right?

Q: In the 1980s.

A: So I send it to Fela and Fela said to tell them to come back in like two years.

Q: Why?

A: That’s the question they asked. He said the spirits told him so. When somebody says that to you, how do you respond? First of all, I don’t jump like you did to say it was Professor Hindu’s idea. I just asked him if he would sign a letter saying he couldn’t sign the agreement for two years for personal reasons. He said yes and I went to Beko’s office to bang out a letter and sent it off to Gerald Busby in LA. In the intervening time, our lawyers started to exchange stuff. Two years later, a contract was ready.

The week it was ready for signature, Gerald Busby was sacked and they brought in Andre Harrell, who was president of Uptown Music. And we needed downtown music, man. His first task as president of Motown was to axe Taboo. Femi’s record went straight through the floorboards. The poetic justice here is that we ultimately signed with Universal a licence deal for a sale and they own Motown. And so at the end of the day, I always thought Fela wanted to leave his catalogue for his children. There’s no documentary evidence of this, but that’s my own feeling. And they’ve used it very wisely. You know there’s never a lack of causes, only a lack of credibility. And sometimes it takes time to understand that what’s been done is important.

Q: So how did Fela take the axing of the deal?

A: He didn’t give a shit, man. I think he was probably happy in a way, if I’m right that he did want to give it to his children. I might be wrong of course, but Fela was a shit dad and I think he would have wanted to atone for that with this.

Q: You’ve spoken before of how you don’t think Fela has quite matched Bob Marley in terms of global significance. Do you still hold the same view?

A: Yes, I think it’s true. I think the Marley family have done a stupendous job of making something work for them. We haven’t quite attained that level yet but we ain't finished either.

Q: So is that a model for you—the Marley family model?

A: A model only in the sense of cohesion, sticking together to accomplish a task. We’re looking at ways to achieve all these objectives.

Meeting Rikki Stein

Getting Stein to meet me was easy, and it was his doing. All I had done was point out in an article published here on Music In Africa that Fela was no prophet, that rumours to that effect were greatly exaggerated. A prophet predicts, says so and so will happen at some future time; Fela represented reality. Stein took offence and sent me a stinker DM on Twitter. How had he found me? “I know how to use my machine well,” he said.

My editor and I met Stein at Watercress Hotel, a gaudy place just across the road from Lagos Airport Hotel in Ikeja. Stein was sitting across three upcoming musician types in a sky lounge built into the side of the hotel’s second floor. I should say, before going on, that Stein is the most imprecise Englishman I’ve ever met. Watercress was not beside Lagos Airport Hotel (it took us a few drives up and down Obafemi Awolowo Way to find that out), nor was he on the roof of Watercress when we found him.

How does he get to read everything written about Fela?

“I just use my machine properly, man. I see it all. Some I don’t bother reading, because I can tell it ain't worth reading. I read some pieces and I’m like, what the fuck is wrong with you, man? You can’t even speak English. I mean, if you want to write in Yoruba or whatever, do it 'nau'. But you have to spend some time figuring out how to write.”

Stein is a self-described guardian of Fela’s legacy, so I asked him if he took offence to my article because of his sense of guardianship.

“Absolutely,” he responded. “I’m a genetic manager.”

After reading my piece, he had sent it to Theo Lawson, head of the Felabration committee, who finding nothing to get angry about, sent it to Yeni Kuti (Fela's eldest child) and other members of the Kuti family. They loved it. My editor's theory is that Stein's reaction was based on the headline: 'Fela was not a Prophet'.

Stein is the weirdest Englishman you’ll meet. Every third sentence seems to be hemmed in by a drawn-out “man”. And he says “shit” a lot. That morning, I’d found out he’d been born in East London and currently lives in North London. Which was nice because he had to support either West Ham or Arsenal. Or be a football fan at the very least.

“Football?” he queried. “I don’t give a shit about football, man.”

Q: That’s interesting for an Englishman.

A: Everything I know about football you can write on the back of a postage stamp and have room left over for your name and address. But I do like basketball. My son plays basketball. And I like the speed of it, and the energy.

Q: That’s a bit odd. You don’t like cricket as well? Or rugby? Good old English fare?

A: No.

Q: Seems you’re more American than English.

A: I don’t know about that, man.

Despite his protestations, Stein knew a lot. Knew all the groupies: “They perform an important service.” Knew which two girls in California used to make plaster casts of penises and curate a museum of them. Knew Jimi Hendrix was a hornier bastard than Fela who was a hornier bastard than Stein himself. Knew that women used to queue up for Fela. Knew that time when Fela emptied a jug of water on a hapless German.

They’d been in Switzerland. Stein booked an extra room, as was the practice, to mitigate Fela’s democratic streak should a willing girl be found. This time, Fela had escaped his crowded room to lead off a blond Scandinavian girl—“yummie yummie,” in Stein’s words—to the spare room. Even though they had the key, what they didn’t know was that the hotel, in a fit of hasty supposition, had let the room out to someone else. Mid-action, a florid German businessman type stepped in and asked Fela to get out.

“You get out,” Fela responded. When the German threatened to call the police, Fela got up naked, picked up a jug of water and threw it over the guy. “Now you’ve got something to call the police about,” Fela said.

DMs and Nigerian pop

DM 1

@Rikkistein: Hey, Smarty Pants, Fela was not a prophet? How would you describe someone whose words from 40 years ago are still (alas) relevant today? And waning interest? As time went by the music got deeper and deeper. Listen to ‘Beasts of No Nation’ or ‘Teacher’. And please, can you not find a more adequate word to describe his music than ‘shrill’?? How terribly disappointing to read such disrespectful prose coming from someone who obviously knows how to write. 20 years on since his passing and this is the best epitaph you can come up with? Shame on you!

DM 2

@Rikkistein: Hi Lati, I was, perhaps too hard on you (although I still take issue with the word ‘shrill’. I’d liken his brass to thunder and lightning). You are, though, forgetting one ‘prophecy’ “Music is the Weapon of the Future”. Remember a few years back when they removed the oil subsidy overnight and, perhaps for the first time, the entire population came out on the street, saying “listen to what Fela was saying 35 years ago and it’s still true today.” And his music became anthemic to that protest. And there are people who’ll admit that they wouldn’t have given Fela the time of day whilst he was alive but now acknowledge the validity of his message which, alas, is still appropriate today. I sent your piece to the Kuti’s and have to tell you that they loved it. So I’ve been forced to eat my words! Good for yo [sic].

@Rikkistein: I’d actually wanted to remove good for you thinking that it sounded like sour grapes, which isn’t at all what I wanted to say, instead of which I sent the message incomplete.

Getting Stein’s opinion about the contemporary scene had derailed a number of times. Eventually, he got to it. Unlike Fela, who was kind and considerate, he said, kids nowadays think too much of themselves. Regardless, Stein believes Wizkid and Burna Boy are doing interesting work, even if he doesn’t take pop music too seriously. He likes Brymo, 2Baba, DJ Spinall and Adekunle Gold. But what he’s most interested in is what’s bubbling underneath. At which point he confessed Fela’s obsession with sweets.

Commentaires