Op-ed: Uniting the world through pan-African rhythms

By Katherine McVicker

On 25 August, it will be 38 years since Paul Simon’s seventh studio album, Graceland, was released. The album won the Album of the Year at the 1987 Grammys and became and remains Simon’s bestselling work of all time.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo performing with Paul Simon.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo performing with Paul Simon.

This success was not just because of its eclectic mix of genres such as pop, rock, a cappella, zydeco and South African music genres like isicathamiya and mbaqanga, but also because it was a political statement, particularly because it came at a period when Western musical artists and organisations had decided to impose a boycott of South African art and music due to the country’s apartheid policy.

But more importantly, the album launched the international careers of some of the South African bands featured on it, such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo, which won its first Grammy Award in 1988, and started touring the world after that. The band has won four more Grammy Awards since then.

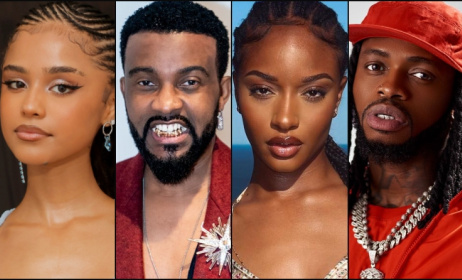

There have been efforts to recreate such a cross-cultural project since then, the most notable being Beyoncé Knowles’ 2019 The Lion King: The Gift, in which she featured the likes of Wizkid, Burna Boy, Mr Eazi, Tiwa Savage, Yemi Alade, Niniola, Busiswa and Shatta Wale, among others.

One thing that the two projects, and other similar ones on a smaller scale, are pointing out is that African music is the music of the future. With Africa currently having the youngest population, there is no doubt the continent will play a major role in the arts and creative industry in the future. The trickle will soon become a flood. As such, one would expect that cross-cultural projects like Graceland and The Gift will happen more regularly.

As the successes of Graceland and, to some extent, The Gift have proved, there are a lot of benefits that a cross-cultural music project can bring. To cite a hypothetical example, what if Temilade ‘Tems’ Openiyi, who has lately become the face of the non-mainstream genre of Nigerian music known in fan circles as altè, collaborates with American jazz artist and Grammy Award winner Samara Joy on a Graceland-type project that will include a joint EP and support for a humanitarian cause for the local communities of the two collaborators?

For Tems, a collaboration with a Grammy award-winning artist like Samara Joy could bring international credibility to her music. To understand the implications, it is worth noting that in Europe and North America, jazz has a tremendous influence on popular music culture. Its artists often dominate music awards like the Grammys. African artists who have won or been nominated for Grammy awards, like Fela Kuti, his son Femi Kuti, Miriam Makeba, Angélique Kidjo, and Hugh Masekela, among others, are either full jazz artists or have a heavy jazz influence in their genre of music.

In other words, a jazz EP might be exactly what she needs to finally achieve the type of musical appreciation on the world stage that her music deserves, and that her predecessors like Kidjo and Makeba have achieved. Apart from Tems, another pair of Nigerian altè musicians who already have a strong enough fanbase are Omah Lay and Johnny Drille, while Richard Bona and Chief Xian aTunde Adjuah are two US-based Afro-jazz artists that could benefit from the new African market that a culture exchange can bring.

For Samara Joy, a collaboration with an artist with a local fanbase like Tems might be an opportunity to make inroads into the African market. While African fans might not be big on jazz like Europeans and Americans, the success of Fela Kuti and Hugh Masekela proves that jazz combined with local content and aesthetics can thrive in the African music scene, which would be a win for an artist like Samara Joy who gets to expose her music to new audiences. And what’s more, since Samara Joy is African-American herself, her music will not come with the accusations of paternalism and cultural appropriation that detractors assailed Graceland with when it was released.

But even beyond the artists themselves, a culture exchange project would be a delight for concert promoters and other music industry professionals across different African regions and also give global touring opportunities when the American artist decides on reciprocity to the collaboration partner artist from Africa.

Graceland was perhaps the first highly successful example of a music and culture exchange between Americans and Africans, but it will not be the last because it is no longer an exaggeration to suggest that African music is the future. However, there needs to be a mechanism that will ensure that firstly these exchanges can happen more often and, secondly, that it is a true cultural exchange that both parties benefit as equally as possible. That way, people from around the world can enjoy a taste of African music, and African music can bring some value to the African continent itself. Building that structure is what we are trying to achieve at Arts Connect Africa.

Katherine McVicker is the founder of Arts Connect Africa and director of Music Works International.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments