What's wrong with Ghana’s music awards?

One day in 2014, Ghanaian reggae-dancehall Shatta Wale arrived online angry. The subject of his fury, as different from his general irreverence, was Ghana’s top ranking award show, the Vodafone Ghana Music Awards. In four videos the man formerly known as Bandana castigated everyone affiliated with the VGMAs. According to some followers of Ghanaian music, his quarrel with the awards began a year before when he lost the Dancehall Artiste of the Year award.

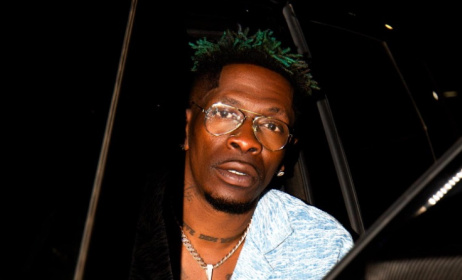

Shatta Wale. Photo: Bigx.com

Shatta Wale. Photo: Bigx.com

His anger was perhaps understandable These things happen. After they have made money, pop artists want respect, they want awards. It is not enough that they have overcome poverty, their work must be proclaimed to be art, to be superior to all others. The VGMAs took the ’Kakai’ singer’s rant seriously. They threatened the artist with a ban. This year his name failed to appear on the nominee list. His fans have complained. They want to know if an artist’s behaviour should affect his chances of recognition?

There were other problems with the nominee list. Mr Eazi, for example, was not nominated—for being Nigerian even if he has worked his music career in Ghana. A coincidence since one of Shatta’s declarations targeted the Nigerian nationality of the head of VGMA organiser Charterhouse. As he said, “Make no foreigner come do awards in Ghana.”

And then the list of nominees for Ghana DJ Awards were released. This was met with another outcry. Why only Accra DJs? The list of nominees took major notice of DJs working in the country’s capital to the detriment of others. if the VGMAs had a personal problem with Shatta Wale, Ghana DJ Awards had a problem with regional bias. For blogger Gabriel Myers Hansen, the VGMA decision to ban the prolific Shatta was deserved. “Everyone has the right to feel embittered about one decision or another the board makes,” he told Music In Africa.

“When this transcends, however, into something poisonous, and disparaging remarks are targeted at the board of the scheme, and these remarks are proven to compromise public faith in the awards as well as undermine the value of the awards then sanctions must come in. And they must be drastic, so that they become an effective deterrent.”

Myers' only issue with the ban is that terms have not being made clear: “Does Shatta get a disqualification from this year’s event? Is it a suspension? Is it a ban? Which of these is he serving?”

As the Ghanaian audience await a response from the VGMAs, reggae singer Knii Lante penned an open letter to the country’s awarding bodies. In the letter, the ‘Thinking Out Loud’ star noted that the categories in Ghana’s award shows are insufficient and poorly organised: “Reggae is bunched up with dancehall which is a travesty of justice,” he wrote.

“True dancehall is yet to be clearly differentiated from Azonto-hall and this leads to people playing all sorts of beats (from hip hop to Azonto) and rapping in patois over them to qualify into the Reggae/Dancehall category. Ghanaian Afropop acts (like Wiyaala and Gasmilla etc) should have their own category. Then there are the many choral groups scattered all over Ghana who are not recognised and awarded nor represented at all.”

For the more profession-specific Ghana DJ Awards, the issues concern the regions as the DJ Awards give the impression that Ghana’s best DJs all work in the country’s capital. This is a shortcoming that has stuck since the inception of the awards. Protests have increased in the last few editions especially as the dominant DJ, DJ Black, who has won the Ghana DJ top award four years in a row, is a DJ from Accra. “This fact lends some credence to the protests,” says Myers.

The problem may be similar to that of Ghana’s Anglophone neighbour Nigeria. Early this year, the Headies, Nigeria’s most respected awarding body, was engulfed in a controversy when an artist considered a shoo-in for an award lost to an artist deemed unworthy. Later it would be a clash of egos between producer Don Jazzy and rapper Olamide. But initially the issue was one of merit. The little fact that it was a voting category was ignored by many. This detail may be the key to the problems plaguing the award bodies around Africa, where awards are organised by commercial establishments. Perhaps the continent’s most popular award is the MTV Africa Music Award which is organised by the music television. Both the All Africa Music Awards and the revived KORA Awards are in place but are yet to truly contest the MAMA’s dominance.

In any case, if commercialism is the problem of the awards, Knii Lante makes a suggestion. “Let us,” he writes, “also have an academy that will be the vanguard for preservation of good and worthy music overseeing all these awards. Let’s not allow profit oriented people and organizations to misrepresent the treasures Ghana has to present to the world by organizing low quality awards schemes and programmes.”

Within those words maybe the solution to the persistent problems of Ghana’s awards. But is anyone listening?

Comments

Log in or register to post comments