KECOBO blocks Kenya’s oldest CMO

The Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO) announced last week its list of licensed collective management organisations (CMOs), effectively sealing the fate for the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK).

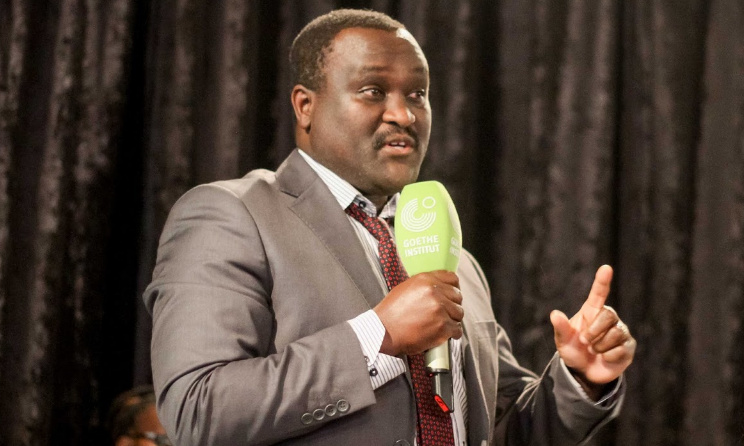

KECOBO executive director Edward Sigei. Photo

KECOBO executive director Edward Sigei. Photo

This after KECOBO cited a 2017 high court ruling that barred Kenya’s oldest CMO from collecting royalties.

KECOBO has now advised business owners to seek licences from authorised CMOs, which it lists as:

- The Music Publishers Association of Kenya (MPAKE), representing authors, composers, and publishers of musical works in Kenya.

- The Performing Rights Society of Kenya (PRISK), representing performers in music and dramatic works in Kenya

- The Kenya Association of Music Producers (KAMP), representing producers of sound recordings.

- The Reprographic Rights Society of Kenya (KOPIKEN), representing authors and publishers of literally works.

Enforcement of copyright law has been a controversial issue in Kenya. Music users have continuously complained about harassment by officers purporting to represent CMOs.

In an article dated 29 August 2015 by Thika Town Today, the secretary-general of the Thika Central Business Traders Association, Alfred Wanyoike, said MCSK officers were soliciting bribes and threatening traders with hefty fines for allegedly flaunting music copyright law.

Similar threats have been reported by matatu (minibus taxi) owners, DJs and ordinary citizens. Reports of swindlers impersonating copyright enforcement officers have also been rife.

The public notice has come in light of the past incidences as KECOBO seems to be tightening its regulatory grip on the sector.

Speaking exclusively to Music In Africa, KOPIKEN general manager Gerry Gitonga gave some background information about copyright regulation in Kenya. The veteran intellectual property lawyer actively participated in attempts to streamline the sector.

“There are people who feel that the crackdown on the MCSK should have come much earlier,” he said. “However, best practice the world over shows that it takes about 10 years for a CMO in the publishing industry to operate at optimum level. Though MCSK has been around since 1982, it only came under proper regulation in 2006. I think the regulator was giving MCSK time and letting them learn from their mistakes, but change didn’t come fast enough.”

To secure its initial license, KOPIKEN had to present several documents for approval. They were required to prove that the operation was not-for-profit and present a business plan. The body also has to report to the KECOBO board on a yearly basis to renew its licence.

Gitonga said the delicensing of MCSK signaled a tightening of regulations in the country.

“MCSK collected about $4m in the year they were shut down. This shows that KECOBO is taking no nonsense. The regulations have always been there but we are seeing a renewed vigour by the regulator to clamp down on non-compliance. As African CMOs we are still light years behind our global peers and we still have a lot of work to do alongside our regulators.”

On their part, Kenyan CMOs are finding practical ways to increase royalty collection. Last year, CMOs took a different approach, striking licensing deals with representatives of various music users to increase compliance. It was a shift from the acrimonious enforcement of copyright law to seeking compliance by way of collaboration.

Special rates were negotiated for the Kenya Association of Hotel Keepers and Caterers (KAHC) and the Pubs, Entertainment and Restaurants Association of Kenya (PERAK). Another landmark deal was a memorandum of understanding signed between CMOs and the Media Owners Association (MOA).

Similar deals are currently being negotiated with other players in an attempt to make royalty collection cheaper and more efficient.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments