Nandi Molefe on writing book about SA jazz legends

Legendary bebop supergroup Jazz Epistles occupies a special place in the heart of many South Africans. The band’s ephemeral story is one that is well-known but not told often.

Nandi Molefe is the author of Jazz Epistles: The Living History.

Nandi Molefe is the author of Jazz Epistles: The Living History. Kippe Moeketsi, Jonas Gwangwa and Hugh Masekela were members of legendary bepop group the Jazz Epistles.

Kippe Moeketsi, Jonas Gwangwa and Hugh Masekela were members of legendary bepop group the Jazz Epistles. Jazz Epistles: The Living History book cover.

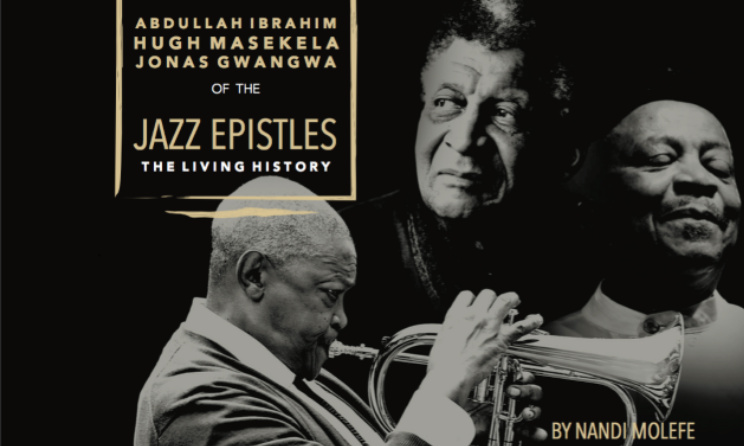

Jazz Epistles: The Living History book cover.

The Jazz Epistles comprised the late Hugh Masekela, Kippie Moeketsi, Abdullah Ibrahim, Jonas Gwangwa, Johnny Gertze and Makaya Ntshoko, who were all cast members of King Kong the musical. The band released one album, Verse 1, before it was disbanded in the 1960s. They united after 59 years for a reunion concert in 2016.

This historical account is now preserved in a 62-page black and gold hardcover book that details the lives and musical stories of Ibrahim, Masekela and Gwangwa, titled Jazz Epistles: The Living History.

The book was written by public relations specialist Nandi Molefe who is the founder of Dominion PR and was recently appointed on the board of directors of Downtown Music Hub. Born in Australia, Molefe always had a passion for music that she has expressed in the book, and by organising the Jazz Epistles’ reunion concert in 2016.

Music In Africa caught up the author of Jazz Epistles: The Living History to find out about her journey while compiling the book and the experience she had with the Jazz Epistles during this time.

MUSIC IN AFRICA: What is it about the Jazz Epistles that compelled you to write the book?

NANDI MOLEFE: I think the fact that they are so accomplished in their individual capacities is impressive, and the fact that they were also successful as a group that filled up jazz halls in Cape Town and the Gauteng region. It’s something that I was personally inspired by. There was such a level of excellence on an individual and group level. Normally, what happens is that there’s this huge successful group and the lead singer breaks away, the group disbands and the lead singer follows the path of Beyoncé. Theirs was a different story at a different time.

Jazz is extremely technical. Yes it is subjective in terms of your interpretation but a genre like bebop puts more emphasis on listening than it does on enjoying. It’s not the kind of music that you put on and people get drunk to while they have a loud conversation or dance the whole night. The aim that the artist tries to push towards is that you go on that journey with them. Jazz Epistles was not just this rock-star band or a pop commercial band, they were a very technical and arty group of young black men who told it how it was in their own musical way.

What was your relationship with the Jazz Epistles and their music before writing the book?

I was only really introduced to the Jazz Epistles when planning the concert. I didn’t really know them at all. But I had listen to a lot of Abdullah Ibrahim, Jonas Gwangwa, Hugh Masekela and Kippie Moeketsi. It’s an interesting interpretation to see that township jazz became South African jazz. South African jazz was born in the township and, in a sense, township jazz remained in the township even though it expanded. It didn’t migrate. So if you had grandparents who lived in the hood – my hood is Soweto – you’ll know that jazz was the backdrop music of Sunday. On Saturdays you’d clean the house to R&B and Sunday was about seven colours and jazz music.

During times of sentimental family reunions, that’s the kind of music that was played. It has a certain type of joy and reminiscence of a good time regardless of the tough conditions of those days. It’s the music that really unites the language groups of South Africa. This is the reason why Sophiatown was a melting pot. A lot of people came for the art, they were true to the art and they loved the art before they were in love with the fact of being a Xhosa woman or a Sotho man.

What was it like being in the presence of the three legends you profiled in the book and how did they feel about you compiling it?

It was humbling. I’m sure they had been to many interviews already. It was something that I was nervous about because I wasn’t a seasoned journalist and this was the first time I was writing something like this. The time was very limited because they were rehearsing, so trying to get them from all four corners of the world for this performance was a hassle to begin with. I was honoured to have that opportunity, which I took very seriously.

It was a long process of back and forth trying to get the timeline together and really sharpen the picture about how it all developed. I wasn’t able to get a hold of Makaya Ntshoko who was in Switzerland. It was nerve-racking and humbling. It’s the biggest assignment I’ve done in my life – second to giving birth.

They wanted to understand what the meaning of the book was. They really wanted to understand the direction of what it was. I had different sections. They didn’t really have the book concept together. When I was interviewing them, I remember Bra Hugh’s manager saying: ‘I just want to know where in the book this is going because you are asking what his name was as a child and when he fell in love with jazz. How do those come together in terms of putting together the concert and book. There are three guys, are you asking everybody this?’

They had to trust my vision for this historical encounter and contextual book. In the end I’m grateful that they were happy to work with me.

What kind of conversations have come up since the book was released to the public?

It has become so much clearer now that this story has not been told many times. It’s unfair to say it hasn’t been told at all, but it hasn’t been thoroughly explored. For me that’s been the red flag. I think before getting into any argument around it, exploring is something that we need to do. Telling the story is the first conversation that needs to happen. The conversation is around the jazz genre. It was the beginning of their careers, they were young when they met and they developed into these grand legendary musicians with signature sounds and riffs recognised the world over.

The songs they were composing were about themselves. There’s ‘Blues for Hughie’ for Masekela and ‘Dollar’s Moods’ for Ibrahim. The band said the inspiration was drawn from the members internally. That becomes interesting to see and to study against what kind of artists they became in their individual capacities.

Comments