Malian music in exile

By Oualid Khelifi

Malian music has been acclaimed for decades on the world's most eclectic stages. Dozens of artists, deeply rooted in their ancestral customs, have taken the sounds of this Sahel landlocked African country far beyond national and continental borders. While themes and genres have varied greatly, the essence nonetheless has remained profoundly attached to the land. The conflict that hit Mali in 2012 - the repercussions of which are still felt today - has prompted both old and new generations of Malian musicians to seek exile in other countries.

Songhoy Blues.

Songhoy Blues.

Festival au Désert

Festival au Désert, a Timbuktu-based landmark event founded in 2001 by a collective of northern Malian artists, was expected to die out following the instability reigning over the past three years, but the team of the festival's artistic director, Manny Ansar, refused to give in. A few months after fighting broke out, in February and March 2013 Festival au Désert looked to tour across Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Algeria in two separate caravans of artists, activists and fans, whose routes would eventually cross in southern Mali. While the French-led military intervention changed the security parameters of this very ambitious 'alternative', the 2013 'Edition in Exile' still took place. The festival’s banner of non-violence and cultural resistance through music and art went global, scoring dozens of solidarity concerts and mini-caravans across the Middle East, Asia, Europe and North America.

The resilience of Malian music in exile has proved so spirited that Festival au Désert has been continuing to host – without interruption - its editions in exile, despite all the odds. In 2015, a caravan set off from the Taragalte Festival in Morocco and made its way south to the Malian capital Bamako, and even further up to the town in Ségou to celebrate the revival of the annual musical rendezvous Festival Sur le Niger. While waiting to head home to the golden dunes of Timbuktu, Manny Ansar's peace caravan in Ségou showcased renowned Malian, African and international artists.

Artists in exile

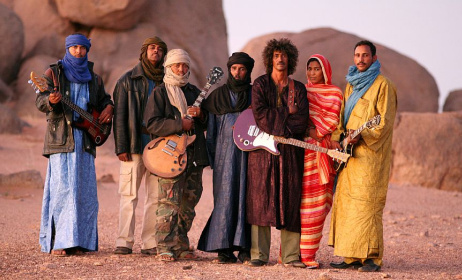

Addressing identity grievances is a recurring topic in Malian music. The renowned Tuareg band Tinariwen saw its debut in exile across the border in Algeria. During the rebellions against the central Malian government in the 1990s, most members of the band fled with their families in the region of Tamanrasset in Algeria's far south. They too performed at marriages and other social events before finding international success.

Grammy-winning Malian diva Oumou Sangaré could also not ignore the predicament of her country. Aside from performing at dozens of solidarity events and musical caravans in the Sahel region and elsewhere in the world, she has gone the extra mile to visit refugee camps in Burkina Faso and other neighbouring countries - singing, dancing and even wailing in grief with her fellow Malians who have driven away from home.

Other ‘desert blues’ legends to get involved include Malian multi-instrumentalist Ali Farka Touré, who sings about his northern village, Niafunké, as well as the culture and tradition of his people and region.

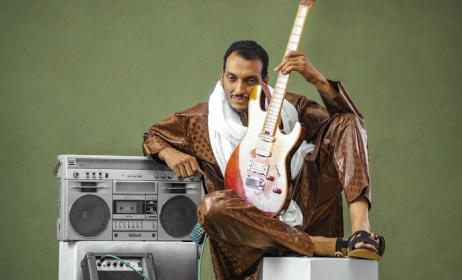

Songhoy Blues

The influence of these icons of Malian music is wholly felt by Songhoy Blues, a younger Malian band that is also increasingly engaged in cultural resistance through music in exile. The four-piece band Songhoy Blues is emblematic of the struggle of other Malian musicians in exile. They sing of hope and of home. With influences swinging between Saharan blues and classic rock, the band is already touring a busy schedule in Europe and North America. Recent events in their country are omnipresent in their lyrics.

It was in summer 2012 when lead singer Aliou Touré teamed up with the other band members, a few short months after ethnic strife stirred animosity in northern Mali. Fleeing violence, Aliou sought refuge in the capital, Bamako, to find that fellow artists from other stricken provinces were also facing displacement away from home. Guitarist Garba Touré had left his native town Diré on the Niger River, while bass player Oumar Touré had to escape troubled Timbuktu further upstream. Nathanael Dembélé from Bamako joined the three as the band's drummer to form Songhoy Blues.

It’s no wonder that Aliou feels that the title of their 2015 debut album, Music In Exile, is emblematic of both the band’s birth and its vision. Both life and music became increasingly dire due to heavy fighting on one side and fundamentalists' bans over playing instruments on the other. “So we became mercenaries too - of music! We performed at marriages and did live shows at street bars in Bamako. We love our music, but we had to survive away from home and family. It has been indeed music in exile”, explained Aliou, adding that he couldn't visit his home for over three years.

The name of the band also cannot be separated from the crisis in the West African nation. Aliou explained: “Songhoy is a reference to the 16th century empire, under which lived our ancestors, either in my northern town, Gao, or the capital, Bamako. We say that we can be together as we did in the past.”

Oumar Barou Diallo - the uncle of guitarist Garba and former bass player of late Ali Farka Touré - told the young band that a group of international musicians and producers were in Bamako under the banner of the Africa Express collaborative project. This ultimately led to Songhoy Blues performing live at Roskilde Festival in Denmark in July 2015 alongside Damon Albarn, Nick Zinner and other renowned musicians from the Africa Express project, including a rendition of The Clash’s hit ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go’, which assumed new meaning in the context of Malian music in exile.

In late 2013, Songhoy Blues travelled to perform in London, where they met the production team of a documentary film about Malian music in exile, They Will Have To Kill Us First, in which they featured as key characters. Since then, international visibility of the band has soared, especially since the film premiered in early 2015 at prestigious documentary SXSW festival in the USA, where Aliou's band had the chance to perform. They also performed at UK's Glastonbury in June 2015.

“When we started touring, the first thing which came to our attention was Africans abroad, I noticed that some people have it good in their countries of exile, others have it bad - but both feel strong nostalgia for home,” stressed Aliou about the message in the band's hit 'Soubour', a word meaning 'patience' in Songhoy language. “In all we do, we call on people to engage in soubour - to give it time.” This much-needed plea Songhoy Blues hopes to carry to the African masses in general, and Mali’s youth in particular.

Aliou admits that while international audiences may sympathise and show enthusiastic support for the band, they cannot fully absorb the nuances behind his band's lyrics and aspirations. The lead vocalist believes that 'Soubour' and other tracks are more likely to resonate with the Malian and African diaspora - refugees in particular. “I meet Africans abroad, I see families separated, children born in a place where they have little or no exposure to their parents' heritage. So the idea of music in exile becomes far more urgent and significant. It is about preserving a culture, to survive even away from its native land. We believe we can do it through music,” says Aliou.

In the last track of their album, simply titled ‘Mali’, Songhoy Blues asks the young generation what Mali’s founding fathers might think of the state of the nation today. “We have a vast, young country and an incredible cultural wealth, which we inherited from our grandparents and ancestors,” elaborates Aliou. “Yes, we can enjoy and celebrate this blessing, but that needs to go with a responsibility to protect it, in order to re-establish peace and harmony in Mali.”

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments