A peaceful riot: Johannesburg’s historic Concert In The Park in 1985

Johannesburg, 1985. In a helicopter flying back from Bophuthatswana, music producer Hilton Rosenthal saw Ellis Park below. He leaned over and told his companion, 702 boss Issy Kirsch, that he had been listening the previous Saturday to a 702 telethon raising money for a local charity and wanted to do something similar – only much bigger. The stadium below, he believed, would be an ideal venue.

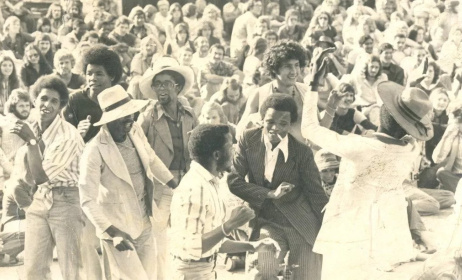

A photo of the historic Ellis Park concert in 1985.

A photo of the historic Ellis Park concert in 1985.

As luck would have it, Kirsch was a friend of Ellis Park supremo Louis Luyt, and said he would give him a call. In a matter of hours, Kirsch called Rosenthal to say that Luyt had agreed to donate the stadium free of charge, and that it was time to get to work.

Rosenthal did just that, in the space of a few days getting 22 of the country’s biggest bands, across all races and genres– a singular feat during the height of apartheid. All artists, as well as the sound engineers, lighting technicians and everybody else necessary for such a concert, agreed to offer their services mahala – all in the name of raising funds for the local NGO Operation Hunger. “We had relatively modest expectations,” remembers Rosenthal. “In my mind, a number around 30 000 would’ve been a fantastic success.”

Incredibly, on that Saturday, 12 January, 1985, it turned out to be almost four times as many. An unprecedented number of people flocked to the stadium in downtown Jozi. There were moments that threatened to turn ugly. “I got a call for help from one of the security people on the side of the stadium,” says Rosenthal. “I came running out and saw this huge crowd outside the gate. People were streaming through the turnstiles with their tickets. The crowd was so large that at one point the gate was lifted off its hinges, and people just poured in. I was praying that no one was going to get hurt.

“Thankfully it turned out pretty well…I think the final number was 125 000 people at the concert. And we know that we sold somewhere around 100 000 tickets, so some people got a freebie at the last minute.”

22 bands took to the stage that day, beginning with Pretoria rockers Petit Cheval, then pop crooner Neville Nash and Mara Louw, who covered 'Motla Le Pula' in lieu of the exiled Hugh Masekela. More slick pop acts followed in quick succession: Supa Frika, the Stimela-backed Street Kids, funk sensations The Rockets, Blondie Makhene doing his gospel-soul routine, and a riveting performance by a wheel-chair bound Margaret Singana. Top white rock bands of the day Ella Mental and Via Afrika played either side of spandex-clad disco-funk act Umoja, who donned monster masks for their finale.

As dusk set in, the concert kicked into top gear with Brenda Fassie – belting out classics like 'Weekend Special' with the Big Dudes, followed by crossover favourites Sipho 'Hotstix' Mabuse (Harari) and PJ Powers' Hotline, both looking totally at home in front of a crowd now three times the usual capacity of the stadium, one of the biggest in the country.

Things turned sour momentarily when American-influenced pop-rock act Feather Control’s performance failed to go down well with the crowd, obviously wanting more local sounds. Frontman Charles Kuhn was struck on the head with a bottle and was unable to continue after only one song. It was the only notable blemish in terms of crowd behaviour on the day, and one that speaks volumes for the varying quality on show, and the half-baked American obsession of most white musicians in the country at the time.

Steve Kekana, nattily clad in crisp white suit, soon got people back in the groove with hits like 'Raising my Family', a song that had topped the charts in Scandinavia and taken the singer to Europe the previous year.

The concert reached a climax with Juluka, the only mixed-race band on the day. “Johnny Clegg showed us that day why he was world class,” remembers Alex Jay, the MC on the day. “He was just a man on his volcano. He was spectacular,” It was to be one of Juluka’s final performances. The band split up later that year when Mchunu returned to rural Kwazulu-Natal, and Clegg went on to form Savuka. Juluka were followed by the most inappropriate of choices, the saccharine Working Girls and Pierre de Charmoy (think Tom Cruise aping Kenny Loggins).

By the time Duran Duran knock-offs Face to Face appeared on stage, the crowd had shrunk drastically, with most of those remaining being of the paler persuasion. Undeterred, Steve Louw’s All Night Radio delivered straight-up, punk-inspired songs like 'Breaking Hearts', before éVoid, also in one of their final performances, drew the curtain on an amazing day with an anthemic rendition of 'Junk Jive'.

Other major names who performed on the day as backing bands were the Soul Brothers and Bayete, while big-selling bubblegum duo Cheek To Cheek provided backing vocals for several of the headlining acts.

'A watershed moment for South Africa'

The Concert in the Park ended up raising in excess of R450 000 for Operation Hunger. More significant than the fundraising, however, was the complete integration of the audience, with black and white dancing side by side, and the peaceful mood that prevailed amongst all. “Integrated audiences were a no-no,” recalls Jay. “They were still legislated no. Here we came along and we just flaunted the whole thing. We didn’t know how it was going to work. It was down to the audience. When I stood on that stage, and looked out on that black, white, brown mix of South Africans, man, they were all on the same page. The artists were up for it, the venue was up for it, but the crowd made the show. Real South Africans. It was their day.”

For 12 magical hours, there was no apartheid. “I think the whole of South Africa at that time feared the potential of violence. The whole of Ellis Park was absolutely jam-packed, with white and black. And everybody grooved. There wasn’t one incident. It was brilliant,” remembers producer Malcolm 'Mally' Watson.

“The mood among the concert-goers was absolutely peaceful,” agrees Rosenthal. “The head of the police force came to me that evening, and said, ‘it’s amazing, when we have a rugby match here with 20 000 people, we have hundreds and hundreds of arrests. Today we’ve only had around 30 incidents, and most of them for people who were drunk and just causing a bit of problems. There’s been very little violence, and we’re actually totally amazed.’”

“It became a watershed for what was to happen in South Africa,” says Sipho ‘Hotstix’ Mabuse. “You’d never had the experience of black and white musicians performing on that kind of stage, where you had 50% of the audience being white, and 50% being black. You’d never experienced such a huge, integrated audience in South Africa. For the first time, South Africans began to know each other through the music, and Concert in the Park was the catalyst in that.”

The concert established a newfound sense unity amongst musicians across race and genre. “It’s the biggest concert that ever happened in the country. I think it still holds the record. But for me, it was the beginning of the idea that we could form an alliance as musicians,” says Clegg. Founded the following year, the South African Musician’s Alliance was built around musician’s shared demands for freedom of movement, association and expression. “Those three freedoms were accepted by the body of musicians, and the Concert in the Park was the first time that we had the possibility of all being together in one place.”

Rosenthal remembers being brought back to earth by a skeptical journalist. “In the afternoon, I walked into the office and one of the radical Sowetan journalists was looking not very happy. He said, ‘I would rather that people were starving than you were breeding fat slaves.’ That was a disappointing comment, but certainly reflective of the political mood at the time. Our relationship was cordial and friendly, but it hit me pretty hard, that clearly, it wasn’t all just a bed of roses.”

Most the concert’s political gravity has been afforded to it after the fact. If it had been a ‘political concert’ from the outset, it would likely have never been the success it was. Ray Phiri believes that although most musicians were politically inclined, there was “nothing political” about the concert itself. “They had their fun and that was it. It never said anything. It was just a good time and go and get drunk.”

Later, other promoters tried to repeat the success of the Concert in the Park; none with the same results. “It’s always very difficult to emulate a magic moment in time,” says Rosenthal. “The Concert in the Park in 1985 was just one of those moments. Cosmically, the planets must have been aligned. It was the right time in the country, and we just got very lucky. There was just no ways that anyone would be able to emulate that again.”

A double LP of the concert was released soon after the concert, featuring songs from all artists who performed on the day, as well as 'Hungry Child', the collaborative, 'We are the World'-styled single written by Bright Blue, who were unable to be there. Since the concert, this has been the only available chronicle of that day, a VHS of the concert only being made available to a handful of industry insiders. In 2010, to mark 25 years since this momentous event in our musical history, a DVD of the Concert in the Park was released in conjunction with 702’s 30th anniversary.

Originally published on 30 July 2010 on Mahala

Commentaires