Ostinato Records' Vik Sohonie talks about latest Sudanese project – part 2

This is part 2 of an interview with Ostinato Records founder Vik Sohonie ahead of the label's September release of Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan. Read part 1 here.

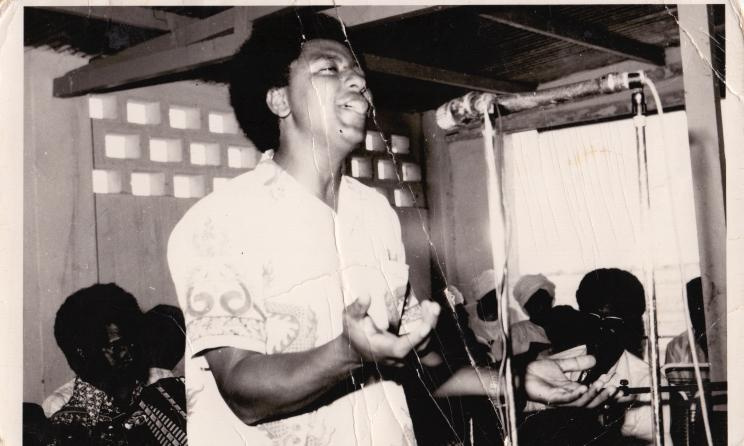

Khojali Osman performs in Omdurman in the 1970s. Photo: Shihab Khojali Osman

Khojali Osman performs in Omdurman in the 1970s. Photo: Shihab Khojali Osman Cover art for Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan

Cover art for Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan Ostinato’s Ahmed Asyouti, left, and Vik Sohonie, right, with singer Emad Youssef at his home in Omdruman. Photo: Janto Djassi

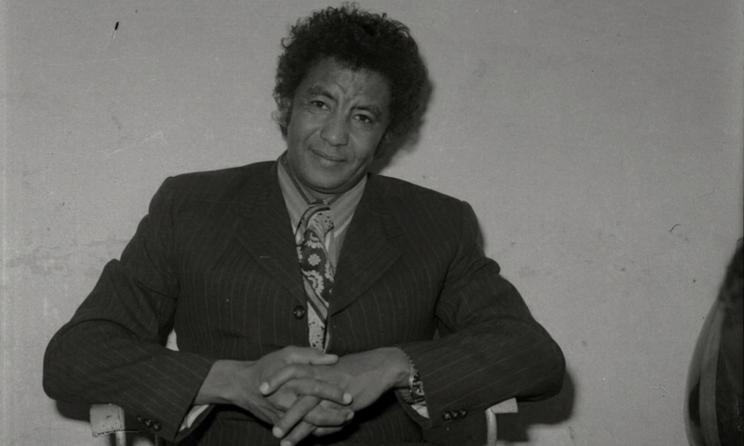

Ostinato’s Ahmed Asyouti, left, and Vik Sohonie, right, with singer Emad Youssef at his home in Omdruman. Photo: Janto Djassi Mohammed Wardi poses for a photograph in Khartoum, Sudan, in the early 1970s. Photo: Fouad Hamza Tibin and Elnour

Mohammed Wardi poses for a photograph in Khartoum, Sudan, in the early 1970s. Photo: Fouad Hamza Tibin and Elnour Legendary singer Salah Ben Al Badia (in black) sings at a wedding in Omdurman. Photo: Janto Djass

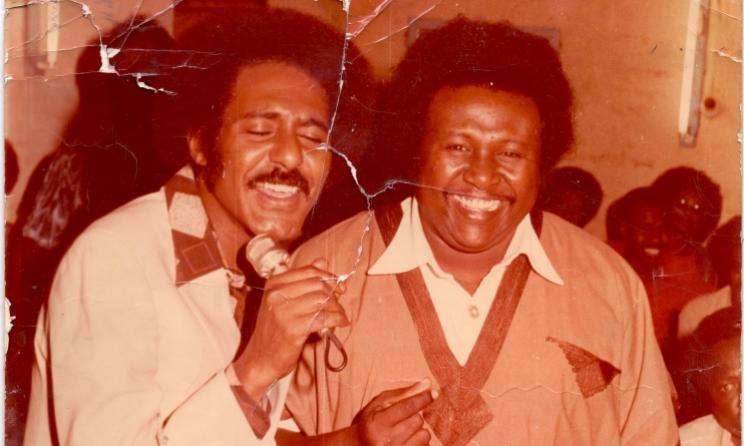

Legendary singer Salah Ben Al Badia (in black) sings at a wedding in Omdurman. Photo: Janto Djass Abdel El Aziz Al Mubarak and Kamal Tarbas perform in Omdurman, Sudan, in the early 1980s. Photo: Kamal Tarbas

Abdel El Aziz Al Mubarak and Kamal Tarbas perform in Omdurman, Sudan, in the early 1980s. Photo: Kamal Tarbas

MUSIC IN AFRICA: Your last release in May was on Sudanese tambour player Abu Obaida Hassan. How did you locate him?

VIK SOHONIE: It took seven years to find all his recordings to know that this was a worthy project to pursue. In Sudan, it took many weeks and a lot of luck! We eventually tracked him down through friends and family members of his wife. He lives on the outskirts of Omdurman, the old capital, in difficult conditions. I'm glad we were able to track him down and bring his music back to life, benefitting him greatly as age has taken its toll.

Given his previous glory and your one-on-one interaction with him, do you feel that the state neglected him?

I would perhaps put it down to how Sudan is structured. There is the centre – the oasis of the capital Khartoum – and the periphery. The periphery can suffer while Khartoum will not always feel the impact. Power of all kinds is concentrated in the centre. Artists from the centre and the central culture seemed to be more protected than those on the periphery. Abu Obaida was perhaps seen as peripheral and as a result was marginalised when the money dried up.

I did find it odd that while so many singers from the older eras in Sudan are still performing and earning good money from mainly wedding performances, Abu Obaida Hassan never really recovered from Sudan’s economic downturn of the 1980s. He admits he wasn’t good with money, but he was a popular artist so the lack of protection he received is problematic.

How is the release doing in terms of sales and reviews?

I’ve loved Abu Obaida’s hypnotic sound for so long, but it is an acquired taste. I’m happy to say that it looks like folks loved it as much as me and as much as Sudanese crowds of the 1970s and 1980s. It sold out within a month and was covered widely by the BBC, and was ranked in the top 10 reissues of 2018 by The Vinyl Factory.

Abu Obaida has benefitted from this release, so in some way there is a kind of justice to his story. I don’t think in a million years Abu Obaida would’ve thought his music would be loved in, say, Poland or Singapore, but here we are.

Which is your most successful music project so far?

The only unsuccessful project I had was my very first, Tanbou Toujou Lou, a compilation of music from Haiti largely produced under the Papa Doc [François] Duvalier era. To me, as a student of colonialism who has always been fascinated with Atlantic history, mainly because our modern, deeply unjust world was born in the trade of human flesh in the Atlantic, Haiti is a place that requires a lot of unpacking, and simply one can’t understand the world today without understanding Haiti.

But I’ll put the lack of success of that album to it being my first release when I was totally unknown. Since then, each release has been more successful than the last, with Sweet as Broken Dates, as a Grammy-nominated album, being the most successful release thus far and one of the most successful compilations of 2017. It was covered extensively in the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Guardian, the BBC, Le Monde and countless other publications across the world. It got the attention Somali music and culture deserves.

During your two-year documentation, are there musicians who stood out more than others?

Every country has its stars, its loved singers, but there are of course titans of their era. In Somalia, I would say it was the female singers in the 1970s who really stood out, as it was a music scene dominated by women. How amazing is that? In Sudan, I would argue it was the likes of Wardi, who was a force of nature, or as his son called him, 'The Last King of Nubia.'

Your East African releases deal with old recordings from countries where copyright law and royalties are rarely implemented, or simply unheard of. How does Ostinato Records handle copyright?

Yes, copyright implementation can be difficult, and it differs from country to country. To find out how a society or culture defines ownership, it requires speaking to lawyers in that country as well cultural leaders. There is a balance to be struck between conventional notions of copyright ownership in western copyright law and the conventions of ownership in societies like Somalia.

There were different approaches for Cape Verde and Haiti as well. Since Sudan was the latest venture, I can talk more about that. Sudan is signatory to global copyright conventions and as such has robust and clearly defined ownership rules. Sudan recognises the singer, poet and composer as owners and we acquired permission from each of these three parties (sometimes it’s one person who filled all three roles) to use each song.

Do the featured artists get a percentage from record sales?

Yes. In Sudan for example, we have a prorated royalty that is evenly split between all artists on the album as well as the poets and composers. They also receive an advance to sign off on usage of the songs. Honestly, many are just happy that the music they recorded 30 to 40 years ago is getting a second life.

Would you say the global market is growing for this forgotten music?

Most definitely. As the world shrinks, as cities become more global, as tastes become more global, and as people are able to discern between the commercial and the authentic, particularly the new hyper-aware generation, this music will always have a place. We are slowly pulling back the veil of colonial perceptions, attitudes, and outright propaganda. This coincides with the decline of western power and the 'rise of the rest'.

There are many labels doing this work and we are effectively rewriting a history that is seldom covered in any school, and has to be vigorously sought out even at the university level. I was sceptical when I began my label because of the market size and interested ears, but I have been pleasantly surprised, and at some point shocked.

People ask me: 'Who’s your target market?' And I always respond: 'I have no idea.' I’ve had everyone from a CEO of a major hedge fund in the UK to a postman in Japan buy my records. I think if you’re internationally engaged in any way, and there are probably more globalised minds today than ever, you’re going to dig a story of beautiful music from places you’ve been told are vapid, violent wastelands, or as Donald Trump’s ilk would call them 'shitholes'.

Do you think African governments are putting in enough effort in archiving old music?

The will is definitely there, it is the resources that are needed. I’ve sat with government people in Djibouti and Somalia who are very keen to preserve their auditory heritage. They just require some technical expertise and funding to do so. Africa has been looted for nearly five centuries, and is still looted today, so it’s not surprising that funds are not readily available for music preservation.

The hope is that Ostinato Record’s projects can inspire global funding for preservation. I can’t reveal much about this but Sweet as Broken Dates has potentially persuaded one cultural institution to invest in the preservation and modernisation of a major archive in Somalia.

What are your future plans?

As someone born and raised in Asia, I will eventually be turning my focus to my home continent as well as Asia’s diaspora in Latin America, a key story that needs to be told through the medium of music. Stay tuned!

Pre-order Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan here.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments