Does Nigerian pop reflect the spirit of the times?

The Germans own the word Zeitgeist. In English, we approximate it to mean 'spirit of the times', the ruling passion of an epoch, the signposts of the grand sweep of history.

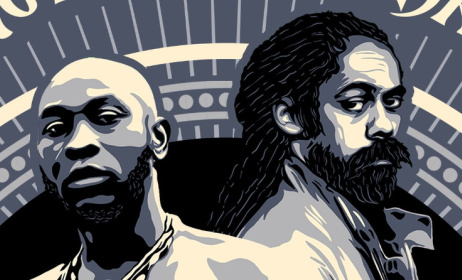

Wande Coal, left, poses in 'Iskaba' video. Photo: 360

Wande Coal, left, poses in 'Iskaba' video. Photo: 360

It’s the sort of thing socially minded techniques of cultural critique have taught us to suspect, however. As the argument goes, it’s the sort of blanket sensibility that validates the inexplicable absence of blacks from F Scott Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age in The Great Gatsby. It’s why we’ve come to see the notion of a 'great something' narrative as problematic. How can something be a Great Lagos narrative when there’s so much it doesn’t—and cannot—say? Still, the Zeitgeist has its uses, even if limited.

A recent much reproduced critique of Nigerian pop by Feyi Fawehinmi asserts that Nigerian pop songs carry no history in the way that Bruce Springsteen’s 'Born in America', for instance, does. More, music separates itself into the woke and the unwoke. The following tests those claims for validity.

If to be woke is to be socially conscious, socially aware, then all music is woke. All music, however outlandish, is a product of its social circumstances, however many different spirits make up these times. If music does not offer a straightforward critique of its times, it at least reflects it. If aspiration is the ruling passion of the epoch, you’ll find it in the fixations of the songs. If it’s rebellion—whatever kind of rebellion, even rebellion against a ruling passion—you’ll find it there. The work of an interpreter of culture is to read cultural productions closely to find the strands that make up these thematic wholes.

Some songs lend themselves to easy social critique. 'Born in America' does. Fela’s music, his Afrobeat particularly, does not require much of the seeker. Fela has done much of the work of meaning-making by explicitly transmuting society into his songs. Situating highlife in its socio-historical epoch might present a little more difficulty than Fela, especially if your idea of interpretation is to pursue explicit code words like “alert.”

But when you prod the songs with questions such as “to whom are they addressed?”, “by whom are they made?”, and “what do they signal?”, a chromatograph begins to emerge. When we ask these same questions of our popular songs, the histories we seek to document, the deeper truths we wish to uncover, will reveal themselves. What relationships, for instance, are there between Nigerian songs (and music videos) and champagne consumption data in Nigeria? How do these relationships comment on Nigeria’s social and economic history?

When Olamide sings about wanting to drive Ferraris and Bentleys, what does it say about the sort of cultural images we consume? The aspiration is straightforward, but what latencies can be teased loose? How does Falz’s 'Ello Bae' fit into the history of African-American cultural influence on mainland Africa? Do Reminisce’s 'Tesojue' and Olamide’s 'Story for the Gods' comment on attitudes towards sex and consent in their times? What is wrong with Skales?

Tekno’s Rara wears a Fela mask, but what insights does it supply into the Nigerian’s attitude towards sociopolitical deconstruction and reconstruction (Hint: Oluwa go bless me.) How is it a signal on the new economic nationalism inaugurated by the recession? Is Qdot’s 'Apala New Skool' not an explicit commentary on the epoch of chache (pronounced cha-che; a corruption of the colloquial Yoruba expression “sase”), an epoch where money is the matter and the means don’t matter? Does 9ice’s 'Living Thing' not corroborate 'Apala New Skool'? What history is wrapped—or not—into Davido’s journey from 'Aye' to 'If'?

There’s far more to history than the economics of inequality or grand events like the Vietnam War. Sometimes, seemingly apparent associations can be misleading, as Levitt and Dubner show us in Freakonomics. FiveThirtyEight ran this experiment to get a sense of the history of language use on Reddit.

History is certainly not the problem of Nigerian popular songs. The absurdest Nigerian song carries a surfeit of history. Those who are equipped to distil method from the madness will do so. Should we be worried about the absurd narratives and chronic lack of coherence in too many of these songs? To say yes is tempting—yes, except that this absurdity too is a manifestation of some sort of history, the history of Nigerian education, the sort of history that produces absurd artefacts like the PhD president. Knowing this, perhaps it is fair to say Fawehinmi’s worries are misplaced.

That Fawehinmi imagines that a parenthesised, throwaway “he’s wrong by the way” is a sufficient rebuttal to Thomas Piketty’s conclusions about historical inequality from arduous statistical and cultural analysis tells its own story about Nigeria and its music. It participates in the same species of shallowness – the same of kind of glib intercourse – Fawehinmi accuses Nigeria’s popular artists of. Don’t get me wrong, a critique of 'Iskaba' is certainly not the best occasion for tangling with Piketty (and a tangle with Piketty would have to proceed on the grounds of the continents of evidence he amassed to his cause), but that’s the more reason why such glibbery should never have been ventured into. On what intellectual grounds might we be persuaded to put stock in the glib rebuttal of an Ayatollah of free market mythicisms that have failed everywhere?

I am sorely tempted to view Fawehinmi’s critique of Nigerian pop through this prism of glibness, because it is a very Nigerian (public intellectual) attitude to eschew the fundamental for the sensational. The cup will pass over, unspilt, because the critique serves to at least throw down the gauntlet to mainstream critics of popular culture. As the example that Fawehinmi cites shows, much of what passes for cultural critique quite frankly tends towards the unwittingly comic.

Interestingly, besides its use of nonsensicals (another history waiting to be compiled), 'Iskaba' is pretty much on narrative. It’s lazy and it’s light years away from the times when Wande Coal wrote 'Bananas' and 'Ololufe', but compared to “Rara” (I really can’t forgive that “Oluwa go bless me”), ThreeWiseMen’s 'Bastard' (which is one of my favourite 'woke' Nigerian songs of the past decade), it manages not to stray from its central conceit.

That said, the most compelling history of Nigerian music is in the evolution of sound. And perhaps this evolution comments substantially about the evolution of the underlying culture of the listenership. After all, if you don’t put work into it, what can wordless Wagner, Bach, Liszt, Chopin, Rachmaninov and so ontell you about European history? What can Akin Euba tell you about Nigerian history? Why did Fela have long stretches of sound? Why did he begin to call his music African classical music?

Producers of Nigerian pop music are beginning to engage with Nigerian musical history in really exciting ways. Qdot’s 'Apala New Skool' is an explicit example. Another somewhat oblique example of this dialogue is Seyi Shay’s 'Yolo Yolo'. The song has been described as housing “different flavors of music genre [sic] from Latin to Salsa to highlife and Afrobeat”, which is all well and good, and evident. But when you consider that Fela folded funk, salsa and highlife, along with other influences, into his Afrobeat, 'Yolo Yolo' makes for an interesting conundrum.

What DJ Coublon, the song’s producer, has achieved with 'Yolo Yolo' is to make the associations between Fela and Latin explicit, associations easy to miss to the untrained ear. How? He isolated, exacerbated and centralised the Latin strain in Afrobeat. The question then is this: Is 'Yolo Yolo' Afrobeat, Latin, neither or both? The answer lies in the latter two of those four options.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments