The last queen of Fuji music

In the household of Fuji, a kingdom of kings, there are no queens.

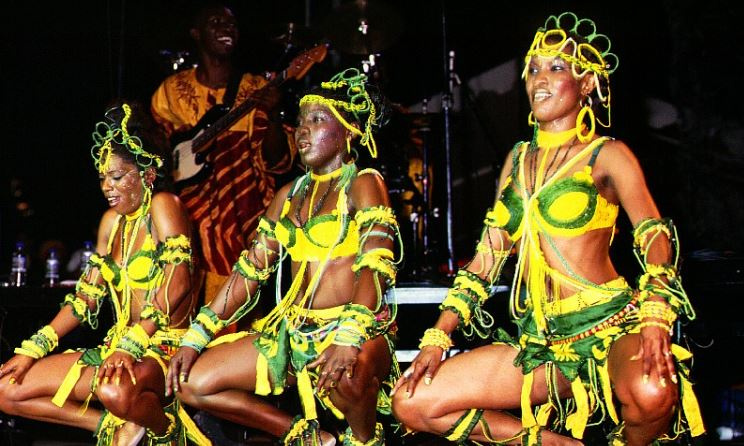

Women are mostly dancers, and rarely singers, in Fuji music. Photo: Robin Zakoura

Women are mostly dancers, and rarely singers, in Fuji music. Photo: Robin Zakoura

Unless, of course, one considers Salawa Abeni, the acclaimed waka queen, as queen of Fuji. This is forgivable. But waka is no Fuji and Fuji is no waka—or so we have ultimately come to accept: Adewale Ayuba came plying his trade in a style quite unconventional to the genre and yet has had it counted as Fuji; Abeni, on the other hand, must have known better than to put her effort at risk by meddling with Fuji, a fiercely contended all-male playfield.

She pitched her tent in an all-female genre instead. Waka, as it is with Fuji, evolved from popular Islamic-oriented traditional Yoruba music, but is mainly associated with female folks of Yoruba descent. Waka can be seen as the female response to Fuji. Take away the gender difference, and it becomes difficult to tell the two genres apart.

In Fuji, the overwhelmingly masculine genre, it is not uncommon to speak of ranking, and its players use colourful and controversial hierarchical terms: Wasiu Ayinde Marshal is King; Abass Akande Obesere is in contention of said kingship; Wasiu Alabi Pasuma is currently Oga Nla (Big Boss), putting himself in fierce contention with Saheed Akorede Okunola, who has jumped the gun to crown himself King above Pasuma and in subtle contention with Wasiu Ayinde. Muri Thunder, Alao Malaika, Suleman Adio, Sefiu Alao, Remi Aluko and many more brawl over one title or the other between themselves. To an onlooker, this can be confusing and sometimes tiring, but to Fuji fans and the musicians themselves these disputes are the lifeblood of the genre. These contentions fuel the fun.

But when an attempt at queenship came up in the early 2000s, there was some disturbance in the household. Fans and musicians were not sure how to relate to Iyabo Alake aka Osanle, a woman with an all-male Fuji band, including the chief back-up singer (The chief backup spot is a prominent one in Fujiland). She called herself a one-woman battalion.

Osanle, a Yoruba nickname for one who ran away from home, was neither beautiful nor endowed—perhaps this could have been a route to securing a niche—but she was bold and loud. She relished praising her own thuggery and rebelliousness against parents and society, but was hardly clear-headed about it: since she also said she wasn't wayward. She called herself Iya won (literally, "Their mother"—mother of all the other Fuji musicians apparently.)

Now, the problem was: there is almost no breeding of such females in the Yoruba society. No woman in the tradition has moral or religious rights to be that sort of rebel, and much more, publicly proclaiming being one. So Osanle was ignored for a long while at the beginning of her career.

However, in what turned out her most lauded album, Aluyo, Osanle disregarded received ideas of her status as a woman in Fuji music. Unlike what the public felt, she deemed her femininity insignificant. Instead, she tried to blend into the scene as it were: self-praising, commending her supporters, improvising her own slangs and finding a spot in the Fuji hierarchy. She played with music with the existing style: she used keyboard, percussions and female choruses in parts of the traditionally long Fuji track. She would even sing of women the way her male counterparts sing of them. Her songs were not feminist.

One of her frequently performed songs tells of a man who brings a beautiful lady to Osanle's own show. This man doesn’t know what it means to make a woman feel good. Another man sees the lady at the show and vows to get her. The second man goes up and sprays Osanle lots of money on stage. That action gets the attention of the lady; he then buys her a drink. The next morning he gets the lady in his car, takes her home, gives her more money, and then has sex with her. At each stage of the second man’s adventure in landing our lady, Osanle asks, like it’s done in a popular Yoruba game: "Has he [the first man] been dismissed or not?"

Osanle never sang of herself as the woman being chased or one who attracted men sexually. She was never the object in her own songs.

Like many genres of music, modern Fuji partly originated from rebelliousness—although not necessarily a conscious one as all Fuji musicians are from humble backgrounds (excluding Adewale Ayuba, who, raised in a middle-class Christian home, saw no usefulness in engaging his contemporaries. Ayuba never got involved in hierarchical controversies and is sort of distinct in his style).

For these artists, there was always the instinct to escape poverty using Fuji music. This sort of hustle sidelines many women. So when Osanle came up publicly claiming vices originally known with male Fuji artists—including singing her songs in a croaky voice—she was a special misfit. The society won’t have any of her. It seemed her fans were only attending to the tired rhetoric of a woman doing better what a man can do. People would even prefer listening to Shanko Rashidi, the then 13-year-old Fuji musician, a promising male thug, than accept the idea of a grown female Fuji musician.

Shanko Rashidi's emergence created space in Fujiland for very young Fuji acts, the recent ones being the 7-year-old Bintilaye and the 13-year- old Destiny Boy. But female acts in Fuji, after the untimely demise of Osanle in 2009, have gone into extinction. Osanle died poor after illness caused by tuberculosis (or was it AIDs as the rumours went?) Her premature death, to the very superstitious Yorubas, was caused by all sorts.

Although none of her male colleagues dissed her in their records at the time—Muri Thunder performed with her—nature may have made an unintended statement for the society that made Iyabo Alake, and this may have the household of Fuji queenless for a long time.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments