Traditional music in Angola

By Analtino Santos

To talk about Angolan traditional music is not so different than other African contexts, where colonialism sought to deny the elements that culturally identified local populations. Specifically with regard to music, the almost non-existence of systematised research led me to consult oral sources during my investigation into traditional Angolan music.

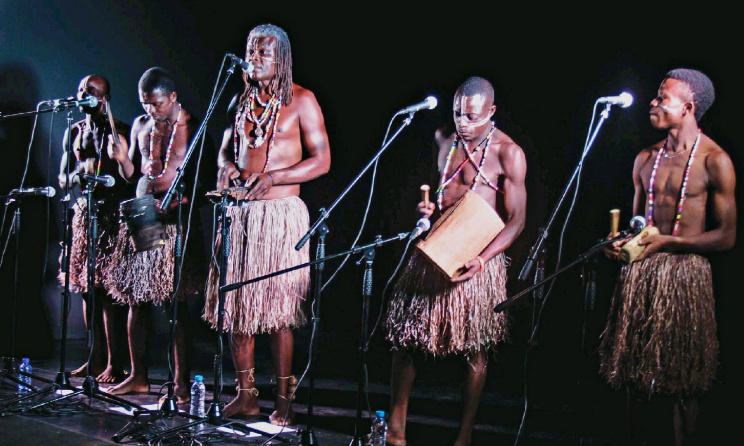

Makuma Mambo.

Makuma Mambo.

Historical context

It was in the Kingdom of Kongo that, in 1482, Portuguese navigators reached the mouth of the Zaire River, in the region that is today Angolan territory, and made contact with the native population there. The Portuguese soon imposed their culture and religion over the people of the area. Christianity became widespread, though traditional forms of music remained[1].

With the birth of proto-nationalist movements in the 19th century, there was a demand to revive traditional culture such as music[2]. In her book Intonations: A Social History of Music and Nation in Luanda, Angola, from 1945 to Recent Times, Marissa J Moolman discusses how “Angola’s urban residents in the late colonial period (roughly 1945-74) used music to talk back to their colonial oppressors and, more importantly, to define what it meant to be Angolan and what they hoped to gain from independence.”[3]

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Angolan recording industry experienced its heyday, with National Radio of Angola (in Portuguese, Rádio Nacional de Angola, or RNA) being one of the biggest promoters of traditional music ‒ as it continues to be to this day. Some key names from the 1960-70s era include Os Kiezos Jovens do Prenda, Bonga, Prado Paim, Alberto Teta Lando and Lourdes van Dunen.

However, with the arrival of national independence on 11 November 1975, many Angolan musicians soon fell out of alignment with the cultural agenda of the communist government with disastrous effects. Many of these new leaders came from the so-called ‘assimilados’ class ‒ or Angolans who, during colonial times, adopted European culture and largely disregarded traditional practices. This created tension between the ruling class and many musicians in Angola, who “used music to form a new image of independence and nationalist politics.”[4]

Instruments and musical origins

Angola is a multicultural country in terms of its ethnic diversity. It comprises more than 100 distinct local ethnic groups as well as Portuguese descendants, other Europeans and immigrants from various African regions, who brought cultural and musical elements that added to the miscellany of traditional Angolan music. Semba, the main Angolan form of urban popular music, is the most visible example of this syncretism.

Jomo Fortunato and Mário Rui Silva, two of the foremost researchers on Angolan urban music, note that semba resulted from a process of transfiguration of traditional rhythms. Licéu Vieira Dias – known as the ‘father of modern Angolan music’ – and his group Ngola Ritmo, are credited for transposing Angola’s percussion sound to the Western guitar idiom. Some of the rhythms that were captured in this way include kabetula, kazukuta, rebita, massemba, kilapanga, tchianda and kakoto[5].

Mário Rui Silva, in his article The History of Angolan Music, states that in the 17th century paintings and illustrations of Giovanni Cavazzi da Montecuccolo, it was already possible to find musical instruments such as the dikanza, ngoma, marimba, kissanji, clochas (double bell) and others, which are still found in Angola today[6].

The same author divided these instruments into:

- Idiophones, such as the saxi or katxakatxa ‒ commonly called the maraca ‒ and the bavugu, an instrument of the Kung people consisting of three greased gourds played on the thigh.

- Membranophones, including the ngoma (drum or tam-tam), once used to send messages, and the mpwita, a friction drum apparently from the Kongo.

- Aerophones, including the mpungu, a kind of horn adopted from Kikongo; the vandumbu, from the Ambwela group in southwest Angola; and njembo-erose, consisting of an antelope horn with a beeswax resonator, an instrument limited to the area of the Herrero group in southwest Angola.

- Chordophones, such as the hungu or mbulumbumba ‒ made up by a bow and a string, also known in Brazil as the berimbau; string instruments rubbed (the kalocha, a type of violin with three strings); and string instruments pinched (the tchihumba, which has five strings or more and a resonator box)[7].

All these instruments are used in the performance of cultural rites and ceremonies during occasions such as birth, puberty, marriage, hunting, rain chants, liturgies, funerals, events to mark the end of mourning, and so forth. Among the many styles that these instruments produce are kabetula, kilapanga, semba, rebita and makinu.

The impact of the civil war on traditional music in Angola

The post-electoral Civil War in 1992 brought many displaced people from rural areas to the biggest urban centres. The capital city, Luanda, became the main centre for settlement and returning national citizens brought home new rhythms.

The visibility of a few of these musicians led to recording sessions at small studios and, ultimately, the use of a parallel distribution channel based on piracy, which enabled the artists to reach audiences through the limited means available to them. It was through this method that most musicians became well known[8]. This fact is little regarded, but it has been recorded in the biographies of musicians such as Tunjila Tuajokola (Malanje), Socorro (Uige), Kumby Ly Xia (Cuanza Sul Province), Baló Januário (Bengo Province) and Beto Bungo (Cabinda Province).

Notable Angolan traditional artists

Kituxi Group: The most internationally successful Angolan traditional music group in the post-independence era is arguably Kituxi e Os Seus Acompanhantes (Kituxi and his Followers) ‒ currently known as Kituxi Group[9]. This group is responsible for inspiring younger Angolan musicians to embrace traditional music. Such musicians and groups include Nguami Maka, Semba Muxima, Jovens do Hungu, Kamba Dya Muenha, Idimakaji, Jabakana, Dilangues da Ambaka, MM Yetu, Makuma Mambo, Novatos da Ilha, União Elite, Kumbilixia, Kietu Uva and Brandão Hamalata. These are some of the groups that can be said to represent Angolan traditional music by their stylistic and regional presence.

Kituxi Group has performed in Hungary, Zimbabwe, Sweden, Germany, Russia, Yugoslavia, Norway, Brazil, Bulgaria and Portugal. The group has released four albums: Nguitambulé (1984), Dingongenu (2001), Kufikissa (2009) and Kene Kumoxi (2006).

Nguami Maka: The Nguami Maka band was founded in April 2002. Translated from Kimbundu into English, the name means ‘We don’t want problems.’ They band explores semba, kabetula, kilapanga and various other rhythms. Initially from Luanda, the group is nowadays engaged in a preservation project for artistic and cultural values titled ‘Tocando os instrumentos da terra, dançando os nossos ritimos’ (Playing the instruments of the Earth, dancing our rhythms). The group has performed across Angola as well as abroad.

Kamba Dya Muenho: Kamba Dya Muenho was founded in the Luanda neighbourhood of Marçal, which is known for its high output of Angolan popular music. Its founder and leader is Lutuima Sebastião[10]. The group has participated in several national and international events and explores musical rhythms and textures from Luanda, Bengo and Malange while engaging in a variety of music styles, including semba, kilapanga, massemba, rebita, kangola, varina, kazukuta, rumba and bolero.

Idimakaji: Idimakaji, which means ‘countryman’, has already performed in several countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Portugal, Venezuela and Germany. The group explores rhythms from Icolo e Bengo, Bom Jesus, Kabala, Mazozo and Caxito, and bases its music on semba, cabecinha, kabetula, rumba and varina. The group has recorded an album called Antónica, released by the ENDIPU label in 2002[11].

Jabakana: The members of Jabakana are originally from Malanje and claim to be representatives of the Ndongo Kingdom, disciples of King Kabongo and cultural promoters of the Marimba region. They play ondangi, madurme, diembe, dibunga and other rhythms from the Ndongo region ‒ some of which are accompanied by masked dancers and traditionally performed on occasions such as weddings as well as circumcision and mourning ceremonies.

Dilangues do Ambaca: Dilangues do Ambaca is a group from Cuanza Norte Province, more precisely from Camabatela in the commune of Bindo, where a music festival takes place every year on 10 July to celebrate the anniversary of the commune. The group plays kassanda, kaienguele, katutula, mukukula, mutobongo, celela, kadissemba, dissemba, kabongo and kabondona, a beat with a marimba sound, and other predominant styles from Cuanza Sul Province. The group uses the following traditional instruments: kacoxa, sakaia, kabontona, kimbende, hungo, ngoma, ndinga, kambanza (a homemade guitar with three strings), dikatu, mutululu (made from animal horns) and others.

Makuma Mambo: Makuma Mambo is a group from Quimbele, Uige Province, in the north of Angola. Its name translated into English means, ‘all problems must be solved’. Adriano Bueloseke, who is also known as ‘Tungulu’, sings and plays the kissanji. It is important to emphasise that the kissanji can be found in several regions of Angola and with different names, including buetete, kalembe or quimkelembe[12]. The music styles that the group explores are kassanji, nsanku, langala, satsumula, kikuekila, ndembo, lupumbo, bumba, kissebele and maringa.

Traditional and modern hybridism

In a cosmopolitan environment, after absorbing more modern influences, some Angolan contemporary artists have come up with a way to present a musical fusion of modern and traditional rhythms.

Gabriel Tchiema blends a number of styles and has a jazz approach to rhythms from the east as well as influences from the Chokwe culture, namely chianda and makoko, among others, creating a fascinating mixture between the traditional and the modern. He is currently responsible for culture in the provincial government of Lunda Norte.

Wyza was strongly influenced by the kilapanga style and its fusion with Afrobeat as well as other more dance-based forms of modern African music. Wyza, real name João Sildes Bunga, was born in Uoge and arrived in Luanda in 1984. He inherited his passion for music from his mother Elsa Bunga, who taught him how to play the kissanji, though when he arrived in Luanda he learnt to play the guitar and became a dancer.

Ndaka Yo Wini is another musician who mixes ancestral rhythms from south-central Angola with textures of jazz, soul, funk and the blues. His background in traditional music is based on the songs he used to listen to during traditional ceremonies. In 2018, he participated at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival in South Africa.

Resources and citations:

[1] Angola: National Geographic Music (2009), last accessed: https://web.archive.org/web/20090628095916/http://worldmusic.nationalgeographic.com/view/page.basic/country/content.country/angola_549

[2] ibid.

[3] Moolman, MJ. Intonations: A Social History of Music and Nation in Luanda, Angola, from 1945 to Recent Times. New African Histories: 2008

[4] ibid.

[5] Fortunato, J. Franco's influence on the sound of Angolan Popular Music (2019), last accessed: http://jornaldeangola.sapo.ao/cultura/influencia-de-franco-na-sonoridade-da-musica-popular-angolana

[6] Rui Silva, M. A History of Angolan Music (2010), last accessed: https://jovenshungu.webnode.pt/products/a-historia-da-musica-angolana-mariorui-sila-

[7] ibid.

[8] Interview with Matadi Makola (2019).

[9] ANGPOP, Cultural center pays homage to Kituxi folk music band (2018), last accessed: http://cdn1.portalangop.co.ao/angola/en_us/noticias/lazer-e-cultura/2018/6/27/Cultural-center-pays-homage-Kituxi-folk-music-band,6417a659-a911-434e-b3d2-9396d2ad7772.html

[10] https://www.pressreader.com/angola/jornal-de-angola/20170525/281801398907528

[11] https://www.pressreader.com/angola/jornal-de-angola/20150216/282007555827984

[12] https://www.pressreader.com/angola/jornal-de-angola/20180415/282467119479316

Disclaimer: Music In Africa's Overviews provide broad information about the music scenes in African countries. Music In Africa understands that the information in some of these texts could become outdated with time. If you would like to provide updated information or corrections to any of our Overview texts, please contact us at info@musicinafrica.net.

This text was translated from Portuguese and a number of the statements herein are based on the author's own research that could not be independently verified by Music In Africa.

Editing by David Cornwell

Comments

Log in or register to post comments