Can Nigerian music transcend Fela?

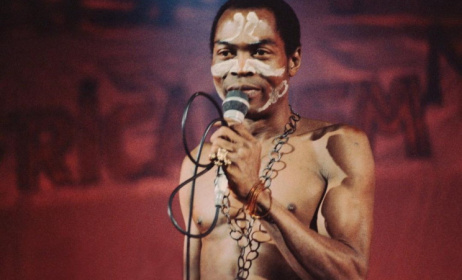

One Fela Kuti image routinely turns up on the Internet. Etched in monochrome and set against a backdrop of stage lights, saxophone suspenders run down a bare torso, two clenched Fela fists tower over a painted face.

It is widely emblazoned on T-shirts and graffiti walls, recognisable like images of Bob Marley, Che Guevara or 2 Pac, as I grew up. If you were born in the early 1990s like me, it is likely the first Fela photo you saw.

True to his name, Kuti, which roughly means ‘immortal’, 20 years after his death, Fela remains a visible cultural icon and represents for millions of young people preternatural cool in fashion and charisma; also rebellion, social activism, and, of course, musical genius. In downtown Lagos, Fela’s music plays on from loudspeakers to shuffling feet in small dark rooms where a lone fan screeches and beer is cheap; there is a Broadway show in his name. Fela is having a moment still. He is acclaimed internationally and commands a vast cult following among everyday people in his home country.

But in Ilesa, a close-knit town where I grew up in the later nineties, Fela’s Afrobeat was rarely heard in the streets, compared to more folk sounds like Fuji, juju, highlife, or even gospel music.

However, I remember being quietly taken by the very black voice of a defiant man declaring an existential right to speak on ‘J’enwi Temi’. He sang, but mostly he chanted ‘o le p’anu mi de’—you cannot gag me—and that song possessed a certain esoteric mystery, in a sense similar to Angelique Kidjo’s ‘Wombo Lombo’ which equally enjoyed regular rotation on radio at that time. 'J’enwi Temi' was rendered in a language I knew but barely understood: the lyrical composition was in a familiar Yoruba; but sonically it was jazzy, groovy, infectious, and funky as hell.

I would not come face-to-face with Fela until after university, marking a passage into adulthood. He became the gift that keeps on giving: at night, while music pulses through the speakers, I would hum to the horns, and take my place in the call-and-response. Fela’s rituals had become mine.

Fela survives in Nigerian pop culture as an inexhaustible trove of inspiration and lyrical template. From Burna Boy to Wizkid, any popular Nigerian artist, born in (or just before) the nineties, it appears, must nod to, or directly borrow from Fela. And there lies the Fela problem: he is scaffold and ceiling, patron and parameter.

Fela Kuti is the one everyone admires without seriously aspiring to transcend. Certain contemporary Naija artists who cannot approximate Fela’s musical range or cultural influence, like Orezi in his recent 'Cooking Pot' video, choose to appropriate him.

Suppose this is why it grates to see Nigerian digital dance music sweepingly identified as Afrobeats—Fela's creation with an 's'. Indeed, the music scene is haunted by the spirit of Fela Kuti, even if much of it should be more appropriately named for a more recent pioneer. It was Terry G who, in his hit song, 'Free Madness', openly declared Nigerian pop music as a widely admitting freestyle session. Fela, on the other hand, was an accomplished composer and multi-instrumentalist, having studied music professionally, and had stints performing as back-up vocalist with veteran highlife musician, Victor Olaiya; and also with the Koola Lobitos band. This already adds up to more rigour, profesionalism, and perhaps privilege, than the emerging Nigerian artiste today can afford.

It is an unfair comparison, and maybe a superfluous one: Fela was from a different time. It was a period Nigerians look back on in nostalgia for a relative sense of order and procedure in attaining upward mobility, but politically, in dread and disgust, for the fact of corrupt military rule. It is a common charge against contemporary pop that the music lacks political merit, or that it is not critical of the government. How often has someone said "Baba Fela don talk am," attributing at paternal affection and authorial clairvoyance to Fela. But it is sufficient to state the obvious: while government misrule lingers, public sensitivity to political scandals has considerably cooled.

Yet it could be argued that Fela Kuti was not merely influenced by the socio-political situation of the country but was rather a congenitally different man. Examples of Fela’s rebellious impulse are familiar: the pursuit of music over medicine; the harem of wives when, as the son of a clergy, he should adhere to Christian monogamist values; the public use of marijuana, still a criminal offence in Nigeria. It is probably this impulse to disrupt that informed his fusion or inversion of jazz, funk, highlife, rock, and traditional African rhythms into the unique, groovy Afrobeat sound.

For most folk heroes, it is unclear where the man ends and the myth begins. Therefore accounts of Fela’s life tend towards hagiography; revealing little or rationalizing apparent missteps. Fela is not called the spirit being, Abami Eda, for nothing.

For instance, Fela is said to have been given to rash judgments, and was rumored to administer his Kalakuta Republic home and concert venue with high-handed paternalism. Much of Fela’s politics pushed the limits of parody: his candidacy to be Nigeria’s president or the blinkered declaration of Kalakuta Republic as an independent nation. To attempt a contemporary feminist reading of some of Fela’s popular hits like ‘Lady’ or, the sexually explicit ‘Na Poi’ is to question his progressive credentials and create an unflattering portrait. At any rate, it would be misguided to remake Fela as saint or sinner.

It is more profitable to realize his imperfection. We must humanize Fela Kuti, ground him in the tangible reality of an idiosyncratic man and socially conscious musician to better access and, perhaps, transcend him. This is especially relevant for emerging artists and culture enthusiasts, those who paint faces in white marks, wear fitting pants, and smoke jumbo. Let us not forget: Fela is way more than the sum of these parts.

Fela was indeed many things but maybe most important was his sense of individuality, artistic creativity and craftsmanship. Consider how many thousand hours he must have dedicated to the mastery of the range of musical instruments he had proficiency in.

Fela, above all, was a true artist, tuned to his own impulses and inspiration. This is why the Fela fixation of contemporary music culture, apart from being formulaic, is anti-Fela. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, it also springs from a poor imagination. It is time for new names.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments