How a record label killed one of Nigeria's finest music groups

We were children of reggae and three decades ago we huddled around a cassette player, waiting for our music-loving uncle to play the new song.

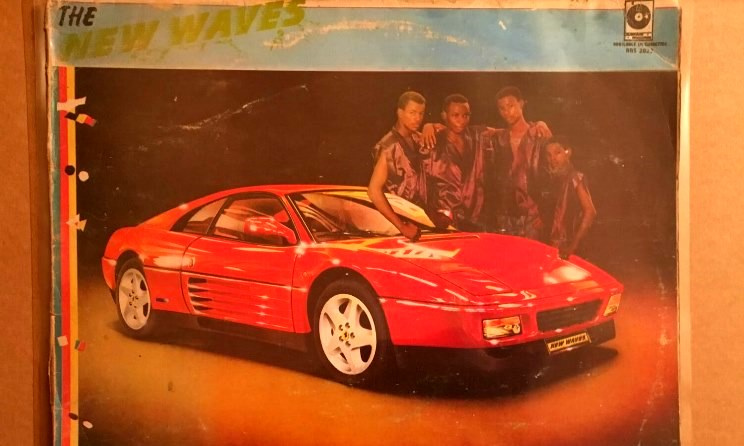

The New Waves (aka Dready Boys) were a popular music group in 1990s Nigeria.

The New Waves (aka Dready Boys) were a popular music group in 1990s Nigeria.

The New Waves, he called them, a group of four youngsters whose fame had just invaded the town.

The first track began to play, its titi-koko beat reminiscent of our bamboo sound experiments as children. It was our own sound and we loved it. The verses were beyond our grasp, but not the chorus: "Dready Boys hit, Ah ye-ye-yen!" For long, that chorus was performed as random karaoke in our course of play.

It was 1991 and reggae ruled southern Nigeria. But a group of juveniles crooning a unique reggae sound was uncommon, hence the result was instant: many youngsters were inspired to form music groups. The waves indeed were new.

Tagged Yardstick, that first album—managed, directed and produced by Average Records—was a hit, reputedly selling over 2 million copies when there was no internet and publicity was assisted by analogue technology. The New Waves (aka Dready Boys)—three siblings and their cousin—hailed from Igbo-Ukwu in Anambra State. The siblings’ father was a London-trained lawyer who also played local music. They all lived in the village and, amid its limitations, made conscious music that mirrored youth, citizenship and ambition.

Within the comforts of Kingsize Place in Ikeja, Lagos, I hold a chat with the youngest, now a gospel artist named St Greg. Then 17, he was the soprano voice of the group, favourite among the group's fans. How did he manage his fame as a teenager?

He admits he had to stop going to class from SS2, studying from home and getting dropped off only to sit for tests and exams. They had not imagined the success that came, nor did their parents who, as Born Again Christians, were opposed to worldly music.

“We didn’t tell our parents,” he says. “During all the studio work, our aunt helped us plan studio trips, lying to our parents that we were off to our maternal home. The song was released on TV and soon we were everywhere. We had to finally report ourselves to dad.”

But dad, who was also a pastor, was miffed both at his offspring's ungodly pursuit and Average Records’ rip-off contract. “He said he was going to sue us to save us. And then sue the record label.”

The second album, City Chaps, was produced within the subsisting contract, the boys now living in the city, reaping fame but not material benefit. Before their father could perfect and execute the planned litigation, he died. Their mum had died four years before. What followed was pain, lack, and all the deprivations their dad had foreseen.

“By the third album, things had gone completely sour between us and Average Records. Even the second album wasn’t promoted as a result. We did not understand the industry. We just loved music and wanted to sing. But music failed us.”

Greg pauses, economical with detail. I remind him that, in ‘Reggae Is the King’, they had sung that “there’s no fire to flame us down”. But I am only pushing my own idealism that they could have used their agonies as material for more music, even as I also praise their lyrical genius.

“It was mostly my brother who had a magical touch to the lyrics. He’s now a lawyer specialising in the music business,” he beams, adding that they did challenge their exploitation in court, with the litigation lasting another 11 years. While at it, they released an album that sold 60 000 copies within hours of its release, before it was shut down by a ban at the instance of Average Records. Under the weight of an unhealthy contract and personal losses, their dream died. By the time they were later awarded 11 million naira ($30 500) in damages, the record label had gone bankrupt, clearly unable to pay more than N500 000 of the fine. “We forgave and moved on,” he declares, drinking the water he has ordered.

“We moved on to other things and God has blessed us. We are all Born Again too. Two of us are successful businesspeople. The other is a lawyer. I also run an advertising and marketing company besides doing gospel music.”

In 2008, they tried reviving the group, shooting some videos for the old songs and also recording some new ones. A music producer loved the new demos and offered to buy the songs at nearly N20 million. “But he wanted us to make the lyrics sexual, saying that is what sells. We couldn’t do that. Besides, you don’t do that in reggae.”

We both acknowledge reggae’s capacity for discipline and how that has robbed it of potential airplay in a lascivious musical era. An organic black product that speaks to our socio-political realities and truths, reggae has lost its space to patently horny imports like R&B and pop.

It’s nearly dead, I tell him, noting the lack of youthful succession as old reggae singers leave the stage.

“Reggae will never die,” replies the man who by turning to gospel may have proven my point: that the market has since moved on. But as we leave Kingsize Place, he invites me to his car, playing me his fantastic reggae demos and winning the argument. He has not moved too far from the source.

Yet to what extent he can keep the reggae vibe going remains to be seen. A Christ Embassy gospel singer, Greg has tens of Christian songs to his credit including 'Have Your Way' with Iyke Onka. His devotion is total. “Singing reggae is not a sin”, he avers, which is beside the point. The point is that the ground has shifted, leaving reggae behind. It is not dead, but existing is different from living.

In its turbulent existence, The New Waves worked hard, writing over 100 songs, producing more than 50 of them, and releasing over 35 in four albums. “Then, we had music companies, unlike now that musicians can do their thing themselves. We didn’t make money.”

Music companies were strong gatekeepers against nonsense content, but they also were gatekeepers keeping much of the fortune from musicians of the era, with many dying in penury. With far more rigour and work, those musicians churned out more music for little gain.

Before finally leaving Greg, I secure a promise that he will organise all of the songs from The New Waves and make them available online, though he reminds me it’s a decision to be made by the group’s members. He begins to play his new unreleased songs in his car. When I get to mine I play 'Apartheid', that old track from the Dready Boys’ first album. The present and the past keep us both in great spirits as we depart. It is a fine jolly moment.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments