Reggae in South Africa

This text provides an overview of reggae music in South Africa, tracing its historical roots to its role in South African politics during apartheid, as well as its current state.

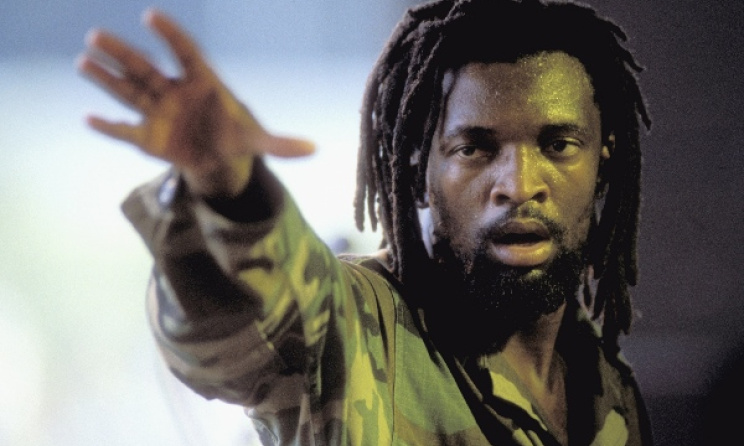

Lucky Dube. Photo: Frans Schellekens / www.mtv.com

Lucky Dube. Photo: Frans Schellekens / www.mtv.com

Origins

Reggae first penetrated South Africa in the 1970s. As early as 1977, Kori Moraba released the album Sotho Reggae on the RPM label. Another early reggae release was by the Dread Warriors, who put out their self-titled album on Gallo in 1983. In the band were the Khoza brothers Gary and Punka Khoza, who had previously played in the multiracial punk band National Wake. The white band Kariba also put out cover albums of popular international reggae hits in the early 1980s. Steve Kekana recorded the reggae song ‘Sound of Africa’ as early as 1981 and wrote ‘Reggae Music’ for the abovementioned Dread Warriors’ album.

These and other early reggae artists were influenced by the Jamaican originators of the genre, some of whom they had been able to see perform live in the early 1980s. Jimmy Cliff was the first Jamaican reggae star to visit South Africa, performing to a multiracial audience at Orlando Stadium in Soweto in May 1980. Bob Marley performed that year at Zimbabwe’s independence celebrations, while Peter Tosh performed in neighbouring Swaziland in December 1983. These performances helped inspire musicians and turned local listeners on to reggae (Djedje, 2012:interview; Siluma, 2010:interview).

Even though it was a ‘foreign’ genre, South Africans quickly adopted reggae as their own. By the late 1980s, artists such as Carlos Djedje, Colbert ‘Harley’ Mukwevho, Lucky Dube, Jambo and the band O’Yaba had become reggae stars. There were also numerous other lesser-known reggae artists, such as Izakka, Pongolo, The Slaves, Prince & The Buffaloes, The Rasta Kids, Angola & The Groaners and Joe Silo, while many other bubblegum (disco) and mbaqanga artists recorded reggae songs. Reggae became an entrenched part of local pop music, with artists of other genres at least referring to reggae in their lyrics, for example mbaqanga stars Mahlathini & The Mahotella Queens’ hit ‘I’m in Love with a Rastaman’ (1990) and Benjamin Ball’s bubblegum hit ‘Flash a Flashlight’ (1984). By the late 1980s, South Africa had become one of the countries outside Jamaica where reggae was most alive (Martin, 1992:202).

Key originators

Carlos Djedje is considered by many to be the father of South African reggae. His style, although addressing local issues and aimed at local audiences, borrowed heavily from Jamaican reggae (Martin, 1992:202). Djedje, whose albums included Remember Them, No Apartheid and Ahoy Africa, saw his role as inextricably linked to the struggle, and his lyrics frequently referred to apartheid injustice.

Another South African reggae pioneer, Colbert Mukwevho, began recording reggae in the early 1980s with the help of the SABC, which needed content for their radio station in Venda. Starting in a band with his father and uncles, The Thrilling Artists, whose third album, Ha Nga Dzule (She Did Not Stay), recorded in 1983, featured one of South Africa’s earliest attempts at homegrown reggae, ‘Luimbo Lwa Reggae’ (The Reggae Song). Mukwevho fronted his own group, The Comforters, who released the four-track EP Month End Lover in 1987. By the end of the decade, Mukwevho had come to the attention of Sello ‘Chicco’ Twala, one of the top producers of the time, who produced Lion in a Sheep Skin (1991), with Mukwevho and his band adopting the name Harley & The Rasta Family. He also wrote and performed a reggae duet with SA’s biggest pop star, Brenda Fassie, named ‘Hero’s Party’ (1990). The song had been originally titled ‘Reggae Party’, but Chicco allegedly “felt the word ‘reggae’ would make him look political, so it was dropped” (McNeill, 2012:91-92).

Inspired by watching Jimmy Cliff perform in Soweto, producer/musician Richard Siluma managed to convince his younger cousin Lucky Dube, then a mbaqanga artist, to record some reggae songs. Those songs proved so popular at live shows that soon Dube was recording only reggae songs. Although Dube was not the first reggae artist in South Africa, he was the first to popularise it on a mass scale, and to define a unique South African style, influenced by the synthesizer-heavy bubblegum sound. Dube’s reggae career began with the four-track album Rastas Never Dies (sic) in 1984, followed by Think About The Children in 1985. It was followed by Slave (1987), Together As One (1988) and Prisoner (1989), some of the biggest selling albums in South African music history, cementing reggae’s popularity and launching Dube’s international career. Dube went on to earn the title of ‘Africa’s reggae king’, displacing Alpha Blondy from Ivory Coast (whose third album in 1985, Apartheid Is Nazism, referenced South Africa). Throughout his career and until his tragic death in 2007, Dube continued to denounce discrimination, segregation and exclusion, and advocated unity among all people (Siluma, 2010:interview; Dagnini, 2011; Goldstuck, 2007).

Reggae and apartheid

Interestingly, from the outset, reggae in South Africa had a multiracial audience. Djedje remembers that when he started, the majority of his audience would often be white, while in time, as reggae became more accepted, his audience reflected a more equal balance between races. With its mixed audience and political message, reggae had a particular power to mobilise people of all races against oppression (Djedje, 2012:interview).

Part of reggae’s appeal also lay in its ability to link people to the rest of the African continent and diaspora – particularly significant in the context of South Africa in the 1980s due to the country’s growing isolation from the rest of the world and the restrictions on movement for black South Africans (Tenaille, 2002:152-3). The majority of major Jamaican and British reggae acts released anti-apartheid songs during the 1980s (including Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and countless others), which promoted solidarity and awareness against the repressive regime.

With its crossover appeal and revolutionary message, reggae was seen as a threat by the apartheid government (Chawane, 2012:173-174; McNeill, 2012:84,93; Martin, 1992:202). It was particularly problematic for censors – although considered “revolutionary” by authorities, it was widely circulated (Martin, 1992:202). Many of Bob Marley’s songs, however, were banned, highlighting the lengths the state was prepared to go to in order to prevent potentially revolutionary music from being played on the airwaves (McNeill, 2012:84). Until the early 1990s, reggae songs were frequently banned not for their political content but for their use of the word “Jah” (meaning God), which upset the censors’ religious sensibilities (Jansen van Rensburg, 2013:99-100).

Like countless other musicians and political activists during apartheid, Aura Msimang left South Africa in the early 1960s. She finished her schooling in West Africa before moving the USA and then settling to study at the Jamaican School of Arts (JSA) in Kingston during the 1970s. Here she had the chance to meet many of reggae’s biggest stars, and recorded vocals (as Aura Lewis) on the Junior Byles hit ‘Curly Locks’. She recorded an album with her own group group, Full Experience, produced by the legendary Lee 'Scratch' Perry at his iconic Black Ark Studios. Unfortunately the full album was never released – only in part over a decade later. Msimang soon relocated to Miami in the US, where she worked on two musical tours with Jimmy Cliff, the first in 1980. After time spent living in Paris and Belgium, she released Itshe in 2000 before finally returning to South Africa, becoming a respected community leader and social worker in Yeoville, Johannesburg. She passed away in December 2015.

Reggae also found support on Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela and other struggle leaders were imprisoned. MK commander James Mange was sentenced to 20 years on Robben Island. On the island he turned to Rastafarianism, growing dreadlocks. A reggae musician, Mange formed a band and taught music to the inmates on the island. He became known as the Bob Marley of Robben Island, with his band playing for the political prisoners on special occasions like New Year celebrations. After his release in 1991, Mange and his band the Whiplashes released numerous albums and performed all over the world. He started his own political party in 1994, the Soccer Party, and later joined the ANC (Dreisinger, 2013; "A Night Of Political History With James Mange", 2013; "Reggae Moonshine Festival", 2013)

In South Africa, as elsewhere, contemporary social problems as well as liberation politics are central to reggae’s lyrical message. For example, Jambo’s album Bad Friend, released on the Cool Spot label in 1990, featured the song 'No Man Kill Another Man', a call to end the violence erupting in KwaZulu-Natal and around Johannesburg between the IFP and ANC supporters that threatened to derail the country’s democratic transition,

Reggae artists continued to play a political role into the early 1990s. In May 1991, South Africa’s top reggae artists - including Dube, Djedje, Mukwevho, O’Yaba and Sister Phumi - performed at a concert called Reggae Strong For Peace. The proceeds of the event, as well as the subsequent live album and video, went towards charity work in Soweto.

Reggae in post-apartheid South Africa

In democratic South Africa, reggae remains a popular genre. Lucky Dube’s global appeal continued to grow until his untimely death in a botched hijacking in Johannesburg in 2007. Today his shadow still looms large over South African reggae, and his absence is sorely missed. His children Nkulee and Thokozani Dube continue his legacy with their own music careers.

Many of the musicians associated with Dube continue to record reggae music. Siluma, Dube’s cousin, producer and manager, continues to perform, now as Saggy Saggila, releasing Endless Love Racing in 2013. Dube’s former backing singer, Phumi Maduna (aka Sister Phumi), formerly a bubblegum star as part of the duo Cheek to Cheek, refashioned herself as a solo reggae artist, one of the genre’s few female stars.

Keyboardist Thuthukani Cele was the man who helped craft Lucky Dube’s inimitable sound and toured the world with him during the 1980s. He parted ways with the group when Lucky was at his peak, forming The Slaves, who released a few albums in the early 90s before changing their name to the One People Band, releasing The Spirit of Reggae in 2014. Maduna and Cele have in recent years garnered a loyal following overseas, touring Papua New Guinea in 2015, for example. Also keeping Dube’s legacy alive is the Lucky Dube Band[i], who released Celebrate his Life in 2015.

Carlos Djedje also remains active, releasing a new album, Conscious Reggae, in 2015 and performing in Germany and Malaysia in 2014. Colbert Mukwevho remains a revered figure in Venda/Limpopo, still going strong as a solo act, continuing to tour the country and release new albums[ii], often performing with his son Percy (aka P. Postman)[iii]

Beyond the old school, one of the most successful reggae bands of the past 15 years has been Tidal Waves, who write and perform original reggae music with blues, mbaqanga and rock influences. Their albums include Hard Work (1999), Harmonijah (2002), Muzik an da Method (2005) and Afrika (2007). To mark their 10-year anniversary in 2009, they recorded their fifth album, Manifesto, and completed a nationwide tour. They have performance all over the world, including in France, Germany, China, the USA, New Zealand, Mozambique and Swaziland Africa.

Reggae artist Black Dillinger was born Nkululeko Madolo in Gugulethu, Cape Town in 1983 and grew up amidst anti-apartheid protests. He started performing in 1999. In 2004 his song ‘Big Trouble’ was featured in the renowned German magazine Riddim. The young Rastafarian soon relocated to Berlin and signing to German reggae label MKZWO and releasing his his debut album Live And Learn in April 2007, featuring reggae artists from South Africa, Germany and Jamaica. His other albums Love Life (2009) and Better Tomorrow (2011). He continues to spend his time between Germany and South Africa.

Another popular roots reggae act is the Cape Town-based Azania Band, while The Rudimentals have for over for a decade been a popular live act with their energetic brand of ska. In Kwazulu-Natal, family band Undivided Roots are slowly making a name for themselves.

As elsewhere in the world, the sound of modern reggae is undoubtedly dancehall. During the 1990s, dancehall MCs like Shabba Ranks were becoming popular in mainstream black American pop music. In South Africa, kwaito followed a similar direction, most notably with Zimbabwean-born Jah Seed’s role in Bongo Maffin and Junior Dread (aka Junior Sokhela) with Boom Shaka.

Jah Seed later teamed up with DJ Admiral (aka Andy Kasrils) to set up the African Storm Soundsystem[iv]. The pair have hosted the successful weekly Reggae Nights at the Bassline in Newtown, Johannesburg for some 20 years, as well as the African Storm Dancehall Queen dance contest. Other popular reggae venues in Johannesburg include House of Tandoor and the Rasta House in Yeoville.

Promoters hosting reggae concerts in recent years include People of the Sun and Lionness Productions[v]. These and other promoters have helped bring a number of top Jamaican dancehall acts to South Africa over recent years, include Sizzla and Luciano.

Dancehall continues its upward trend in South Africa, led by local figures like Jah Crucial, Nathi B, Crosby Bolani, Daddy Spencer, Ras Sugah, Blak Kalamawi, Lord Harmony, Negus I (aka Ras Mabandla), Rastaman Nkushu and Jeremiah Fyah Isis.

While reggae retains a loyal following in South Africa, the genre no longer enjoys the commercial and popular success it enjoyed in the 1980s and 90s. Out of the mainstream, and with limited airplay on radio and television, it is the domain of loyal fans, many part of the country’s large Rastafarian community (Chawane, 2012). Popular online magazines serving the local reggae scene include Mzansi Reggae[vi] and Mafled[vii]

References

- "A Night of Political History with James Mange". 2013. Available online at <www.mzansireggae.co.za/a-night-of-political-history-with-james-mange-2/>. Accessed on 15 November 2013.

- Chawane, M. 2012. "The Rastafari Movement in South Africa: Before and After Apartheid". New Contree 65, pp. 163-188. Available online from <http://dspace.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/8266/No_65(2012)_Chawane_M.pdf?sequence=1>. Accessed on 12 May 2014. Pp. 173-174.

- Dagnini, JK. 2011. “The Importance of Reggae Music in the Worldwide Cultural Universe”. Études caribéennes, 2011.

- Djedje, C. 2012. Personal interview conducted telephonically on 18 September.

- Dreisinger, B. 2013. “In South Africa, A Reggae Legacy Lives On”. Available online from National Public Radio website at <http://www.npr.org/2013/03/30/175583890/in-south-africa-a-reggae-legacy-lives-on>. Accessed on 13 December 2013.

- Goldstuck, A. 1997. “Lucky Dube: A Complete Human Being”. Available online from the Mail & Guardian Thought Leader blog at <www.thoughtleader.co.za/amablogoblogo/2007/10/19/lucky-dube-a-complete-human-being>. Accessed on 21 July 2013.

- Jansen van Rensburg, CE. 2013. Institutional Manifestations of Music Censorship and Surveillance in Apartheid South Africa with Specific Reference to the SABC from 1974 to 1996. MA thesis. University of Stellenbosch. Pp. 99-100

- Martin, D-C. 1992. ‘Music Beyond Apartheid?’. Garofalo, R. (ed.) Rockin the Boat: Mass Music and Mass Movements. South End Press. p195-207.

- McNeill, FG. 2012. “Rural Reggae: The Politics of Performance in the Former ‘Homeland’ of Venda.” South African Historical Journal 64(1). Routledge p81-95.

- "Reggae Moonshine Festival". 2013. Available online at <www.reggaemoonshinefestival.blogspot.com/p/in.html>. Accessed on 18 November 2013.

- Siluma, R. 2010. Personal interview conducted on 12 January in Johannesburg.

- Tenaille, F. 2002. Music is the Weapon of the Future. Chicago: Lawrence Hill.

Comments

Log in or register to post comments