How can we save live music in South Africa?

South Africa once boasted a thriving live music scene, but in recent years it has become increasingly difficult for musicians to secure regular live gigs - an important revenue stream in the modern music industry where album sales can no longer guarantee a reliable income.

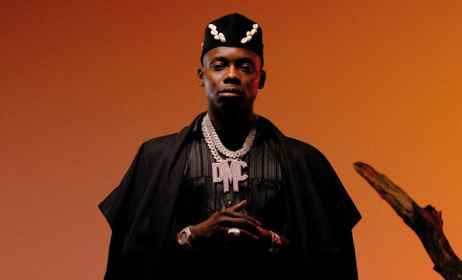

Louis Moholo and Mandla Mlangeni. Photo: Niklas Zimmer

Louis Moholo and Mandla Mlangeni. Photo: Niklas Zimmer Andile Yenana. Photo: Concerts SA

Andile Yenana. Photo: Concerts SA Salim Washington. Photo: mg.co.za

Salim Washington. Photo: mg.co.za

Making matters worse for musicians is that South Africa is a country where local artists (particularly outside of house and hip-hop genres) are not guaranteed any radio airplay and are therefore not in a position to earn much (if anything at all) in airplay royalties.

Jazz represents a vital part of South Africa’s musical history and a microcosm of the broader music industry in terms of the obstacles its musicians face. A recent dialogue in Johannesburg, dubbed Born To Be Black, brought together prominent jazz figures from three different generations in an effort to unpack some of the issues currently facing South Africa’s jazz fraternity, including the state of the live music scene in the country. The problems they outline provide a starting point to suggest some possible solutions for what needs to be done to restore and sustain South Africa's live music scene, particularly for jazz artists.

Artists need to take control

Mandla Mlangeni of young jazz band Amandla Freedom Ensemble paid tribute to jazz venues such as Tagore’s in Cape Town (and musicians such as Hilton Schilder and Kyle Shepherd who have performed there frequently over the years) and the Afrikan Freedom Station in Johannesburg. These venues represent a hub for musicians to perform and feed off each other’s creativity.

In the absence of venues such as these, however, Mandla feels it’s up to musicians to stage events in alternative locations such as taxi ranks, house parties and schools. “I think too much emphasis is placed on venues, as opposed to artists and musicians actually organizing themselves. There could be a gig every night… We need to have more interventions, where it’s not just confined within a club. You can have a gig at a taxi rank… That’s what I’m moving towards, where you make your music accessible,” he said, citing the days of the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1980s, when jazz musicians performed regularly at political rallies.

"I think there needs to be more emphasis on the artist, where the artists can do those kinds of things and can actually initiate it. There’s Facebook, social media, Instagram, so many things where we can organize ourselves,” added Mandla, emphasizing the need for “agency among the artists”.

Salim Washington, an American jazz musician and currently a professor of music at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, echoed Mandla’s sentiments, emphasising that musicians must take the initiative, particularly in a city like Durban that does not boast a musical hub like Tagore’s or the Freedom Station. “It’s a sleepy town… We don’t even have a weekly jam session in Durban,” he explained. “I tell my students: ‘You guys are waiting for the industry to give you a gig. I’ve got bad news for you: it’s not going to happen!’

“The way to make a music scene is to take care of it yourself,” continued Washington. “You have to love it yourself. If you love the music, and you invest in it, and you like it, then other people will like it too. Because we (musicians) are more discriminating that average, so if we like it, it’s because it has some value. But I think there needs to be more of that entrepreneurial spirit.”

Washington paid tribute to the few remaining venues where performing artists are guaranteed a professional sound system and decent payment. “At the same time, I enjoy playing at places like The Orbit, that has an actual piano, and a backline, and a paycheck at the end of the gig. I’m not going to front, those things are important also, at least to me they are. But I absolutely agree that this is a music that we are the custodians of, and if we can’t love it, then we shouldn’t cry if other people don’t love it.”

Appeal to younger audiences

Another participant in the discussion was pianist Andile Yenana. Now part of a ‘middle-aged’ generation of musicians, Yenana has decades of experience in the industry, including international tours with the late Zim Ngqawana and Steve Dyer. He remembered fondly the days during the 1990s in the multicultural area of Yeoville and later in Melville (former home of the iconic Bassline venue before it moved to Newtown), during which there was a genuine sense of community between jazz musicians and their fans, ensuring regular opportunities for gigs – something that does not exist today.

While today’s younger generation of artists “don’t seem to be worried so much about the gigs,” Yenana also noted that jazz enthusiasts from his younger days, who would frequently attend live gigs, are now getting to an age where they no longer want to go out to clubs. “With the generation that I played for, it’s a pity they don’t come out anymore. Some of them are at home now, they watch their own music. They’d rather go the Cape Town Jazz Festival and sleep in the nice hotels. They don’t want to be going out like we used to. I miss those people. But I’m happy to also be playing for a younger generation…. Every new generation will always have something for its own generation, and that is what is happening now. “

Respect innovation and experience

Undoubtedly the harshest criticism of the live scene came from a member of the ‘old guard’, drummer Louis Moholo, now in his mid-70s, a revered figure in European jazz as a member of the influential Blue Notes ensemble that spent decades in exile. Though Moholo returned to South Africa in 2005, he is still struggling to establish himself and cannot find regular gigs, particularly in Cape Town, where he calls home. At first, Moholo was reluctant to speak on the topic, claiming (tellingly), “I don’t really know any venues, I’m still brand new here…. I don’t want to talk about things that I don’t know.”

Prompted by the moderator, jazz journalist Gwen Ansell, Moholo continued, taking aim at the attitude of promoters and authorities, including government as a potential funder of live music. He revealed his disappointment at the lack of opportunities following his return from exile, particularly for more innovative ‘avante garde’ musicians who are not content to simply play the popular styles of the day, such as mbaqanga.

Moholo also noted a high degree of antagonism towards the returning exiles from those who had stayed in the country during the turbulent days of apartheid. 'Local' musicians he feels are jealous, and continue to treat him as an outsider, shutting down potential opportunities for live gigs. “There’s a lot of things that should be brought out in this beloved country of ours. It’s not as sweet as you’d think. A lot of friends of mine have come (back) from Europe, thinking that they’ve come home, that they’re gonna succeed here. But they’ve been disappointed.”

Moholo gave the example of Bheki Mseleku, who returned from exile in the 1990s, only to return to the UK because he couldn’t get any gigs in South Africa. He died in London in 2008. “You come here with big hopes… It’s very disappointing that overseas their arms are open, and here it’s not…” The same he says is true of his contemporary Abdullah Ibrahim, who also does not perform regularly in South Africa, despite his massive reputation. “Many times I think I want to go back because of the attitude,” shrugged the drummer.

Moholo lays the blame mainly at the feet of promoters, who we feels are not willing to take risks with new genres or to experiment with new forms of jazz, an attitude that demoralizes musicians to the point where they abuse substances and end up in an early grave, such as Brenda Fassie. “I think the best thing to do is to conscientise the promoters in South Africa,” he says. “We don’t have a foot to stand on. We want some help. The more we want help from our audience, the more we’re not heard.”

Take the music to the people

By way of a solution, some audience members suggested that it was time for jazz musicians to take music back to the townships, rather than expecting jazz fans to travel at night to wealthier suburban or urban areas.

In response, Siyabonga Mthembu from The Brother Moves On was quick to note that many promoters in these areas are not willing to pay his band more than R1000 (US$65) for a day’s work, simply not enough to support all five members. “We’re not adverse to community work, but the issue is that the South African music industry is set up in such a way that the people who become promoters, handlers and managers, go in with crooked intentions, not thinking of social outcomes. But at the same time, it’s very important that music of black origin goes to black spaces.”

Provide opportunities for young musicians

Whereas Moholo feels the older generation are treated unfairly, Mthembu noted that many young musicians are also left out. He criticised the perception that jazz is for old people, which means that South Africa’s young jazz talent is often sidelined at major sponsored jazz festivals. “It’s because of ageism. There are oligarchs who maintain which youngsters get in, and which youngsters don’t. And the ones that get in are the ones are prepared to shut up and not say anything.”

Where to now?

The recent discussion and the remarks that came out of the mouths of three generations of South African jazz artists paint a worrying picture of a live scene in terminal decline, and an industry full of bitter musicians who largely feel hard done by. But while their problems may appear fairly obvious, the solutions are not quite clear-cut. In the context of an economy in decline, without a reliable musician’s union in the country, and despite the valiant efforts of Concerts SA, it’s hard to see how live performance will ever again be able to offer a steady income to musicians outside the mainstream.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments