Jazz terrorists: South Africa’s musical exiles

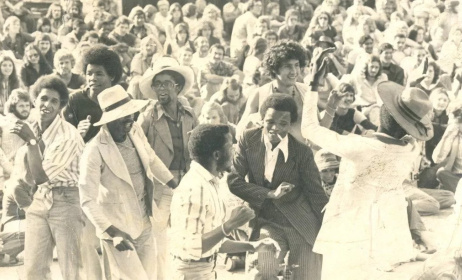

Miriam Makeba – first lady of the Black Panthers; Abdullah Ibraham – living it up in New York’s infamous Chelsea Hotel, Hugh Masekela partying with Jimi Hendrix; Letta Mbulu with Michael Jackson in his prime; Hotep Galeta jamming with hippy icons The Byrds...

The 2008 death of Bheki Mseleku in London was a reminder to us during Heritage Month (September) of a whole generation of artists who were forced into exile and kept in the cold for three decades, while making huge contributions to international music and local politics. Their remarkable careers tell a story that transcends the confines of jazz, one that must be heard by all.

Late pianist Bheki Mseleku. Photo: www.jazzsteps.co.uk

Late pianist Bheki Mseleku. Photo: www.jazzsteps.co.uk Caiphus Semenya in 2015. Photo: Dave Durbach

Caiphus Semenya in 2015. Photo: Dave Durbach Abdullah Ibrahim. Photo: blogs.voanews.com

Abdullah Ibrahim. Photo: blogs.voanews.com

The era begins with bands like the Jazz Epistles, a septet that included Dollar Brand, Hugh Masekela, trombonist Jonas Gwangwa, and saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi, who had played together as teenagers in the Father Trevor Huddleston’s Jazz Band. With skills to match the best American musicians, in 1960 the Epistles put South African jazz firmly on the map when they became the first SA band to record a jazz LP. The epitome of modern, talented, intellectual and international black South Africans, who refused to toe the apartheid line, they were embraced by audiences the world over. Other bands like the Manhattan Brothers and the Blue Notes achieved a similar end.

As a new music embraced by young people of all races, jazz was seen by the apartheid government as a particular threat, and by audiences as the perfect vehicle for resistance.

Two years earlier, in 1958, Todd Matshikiza (father of the late journalist John Matshikiza) had written the “jazz opera” King Kong, about the life and times of a heavyweight boxer. It featured an all-black cast of the cream of SA’s music talent and would ostensibly launch the international career of Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, and others. It was while King Kong toured London in 1960 that events in South Africa took a turn for the worse. Sharpeville erupted on 21 March that year, followed immediately by a governmental crackdown. Prominent musicians were banned and denied the chance to return home, where. gatherings of ten or more people had been declared illegal, mixed-race bands forbidden, black musicians barred from playing in whites-only clubs, and a 10pm curfew left musicians and audiences vulnerable to police “interrogation” at concerts.

As the cultural and political noose grew ever tighter around the necks of South Africa’s top talent, many were forced to flee to greener pastures, where their sublime talents could be recognized.

Miriam Makeba

Before 1960 rolled around, Miriam Makeba had appeared in the anti-apartheid documentary Come Back Africa and attended its premier at the 1959 Venice Film Festival. Instead of being welcomed home in 1960, when attempting to return home for her mother’s funeral, she was refused entry. She took up refuge in London and met Harry Belafonte, who helped her emigrate to the USA, where she built up her career, recording a string of hits in the 1960s. In 1963, after testifying against Apartheid before the UN, her South African citizenship was revoked.

In 1966 she became the first South African to win a Grammy award for the album An Evening with Harry Belafonte & Miriam Makeba. Miriam had become a darling of the American public. After a brief marriage to Hugh Masekela in the mid-60s, Makeba married to civil rights activist and Black Panthers leader Stokely Carmichael in 1968. But this union caused controversy with authorities and conservative white listeners in the US, and her record deals and tours were cancelled. Unwelcome in her adoptive home, the couple moved to Guinea.

Makeba separated from Carmichael in 1973, and continued to perform in Africa, South America and Europe throughout the 70s and 80s. After the death of her only daughter Bongi in 1985, she moved to Brussels. Over the years “Mama Africa” has reportedly held nine passports and been granted honorary citizenship of ten countries. She has twice addressed the UN general assembly, and has been received by leaders like Hailé Selassie, Fidel Castro and JFK.

Hugh Masekela

Hugh Masekela came to the United States via London in 1960 after Sharpeville, with the support of Makeba and Belafonte, as well as Trevor Huddleston. In New York he met and heard the likes of Monk, Mingus and Coltrane, studied at the Manhattan School of Music, and had a smash hit in ’68 with "Grazin' in the Grass", which sold four million copies. Masekela was one of only three black artists to perform at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, along with Jimi Hendrix and Otis Redding. His 2004 autobiography, Still Grazing, recounts his rock ‘n roll lifestyle at the time - friendships with Hendrix, Sly Stone and Mick Jagger, and vast quantities of booze, drugs and beautiful women.

Later, and for much of the 1970s and early 80s, Masekela lived in Africa, in Guinea, Zaire and Botswana, also jamming in the Kalakuta Republic with Fela Kuti. He was one of many, including Miriam Makeba, to perform on Paul Simon’s Graceland, defending it against accusations that it violated the ANC's cultural boycott. His 1987 hit 'Bring Him Back Home' became the anthem for Nelson Mandela's world tour following his release from prison in 1992.

Jonas Gwangwa

Another member of the Jazz Epistles, trombonist Jonas Gwangwa is another who toured England with King Kong in ’61 before heading to the US and the Manhattan School of Music, with the help of Harry Belafonte. Gwangwa continued to reside in the US for 15 years, often performing with his vocalist wife Mamsie. In the late 70s, he toured Nigeria, Botswana (with Letta Mbulu), US and UK.

During the 80s, Gwangwa served as director of Amandla, the worldwide ANC cultural ensemble tour. An official "enemy of the state" for many years, Gwangwa narrowly escaped death in 1985 when his home was blown up by South African security forces. He still walks with a limp. His contribution and commitment was recognized with a standing ovation at the 1987 Oscar ceremony, where he was nominated for his work on the music for Cry Freedom (ultimately losing out to Dirty Dancing).

Hotep Galeta

In 1961, at the age of 20, Hotep Idris Galeta (then Cecil Barnard) left South Africa by boat, bound for England under an assumed name with the assistance of underground connections. He immediately hooked up with his King Kong compatriots, who helped him settle down in a new environment. A year later, he moved to New York. For two years in the late 60s he played in Hugh Masekela's band, including at Monterey. He also played with David Crosby and the Byrds. In 1985, jazz great Jackie McLean invited him to teach University of Hartford's Hartt College of Music in Connecticut, where he remained for the next six years.

Abdullah Ibrahim & Sathima Bea Benjamin

While some were quick to move abroad after King Kong, Dollar Brand returned home to Cape Town, where he had met Bea Benjamin, then a schoolteacher moonlighting as a jazz singer, two years earlier. Refused entry to both medical school and music conservatory because of his race, he nevertheless reveled in the jazz scene of early 60s Cape Town, which was a New Orleans-like jazz mecca and melting pot of cultures and sound. By 1962, Ibrahim and Benjamin found the political situation untenable and left for Europe. They settled in Zurich, along with Ibrahim's trio of bassist Johnny Gertze and drummer Makhaya Ntshoko, where Benjamin persuaded Duke Ellington to hear Brand play at the Cafe Africana in February 1963. Within days, Ellington had arranged recording sessions for each of them at his Paris studio. While Benjamin’s recording remained unreleased for decades, Duke Ellington Presents the Dollar Brand Trio (1963) ensured the band became regulars on the European jazz circuit, alongside top American musicians.

Brand and Benjamin married in London in 1965 and moved to New York. Benjamin performed with Duke Ellington’s band in the US at the prestigious Newport Jazz Festival that year. Brand led Ellington's orchestra in five east-coast concerts, ironically playing at wealthy whites-only affairs. Constant touring between Europe and the US took its toll. Brand and Benjamin, with their young son Tsakwe, returned to Cape Town in 1968 and converted to Islam, changing their names to Abdullah Ibrahim and Sathima Bea Benjamin. By then, District Six was being destroyed. After a spell in Swaziland, they again returned to Cape Town in 1973. Ibrahim released the iconic 'Mannenberg' the following year, inspired by the Flats destination of many of those forcibly removed from District Six.

In 1976, shortly after the June 16 Soweto student massacre and the birth of a daughter Tsidi (aka New York underground hip-hop artist Jean Grae), the family returned once more to New York, and to the famed Chelsea Hotel, where they still have a place today. Ibrahim openly joined the ANC and his SA citizenship was abruptly cancelled. While overseas, he helped inspire African American artists do reconnect with Africa. Ellington once told him: "You're blessed because you come from the source.”

Letta Mbulu & Caiphus Semenya

Singer Letta Mbulu also returned to SA after her stint in King Kong, still in her teens. But in 1965 she too left for New York with her musician husband Caiphus Semenya, where she quickly hooked up with her former co-stars in exile. They performed together that year in the Sound Of Africa concert at Carnegie Hall. Performances at the famed Village Gate club began to attract attention, particularly from Cannonball Adderley, who invited her to tour with him, which she did for the remainder of the decade.

Letta and Caiphus soon relocated to the West Coast, joining Hugh Masekela, who had become a fixture of the California scene. Letta and Caiphus flirted with a range of styles, from soul to disco. During the 70s she performed and toured with Harry Belafonte and Herb Alpert, and working with Quincy Jones on the soundtracks of Roots (‘77) and The Color Purple (‘84), and on Michael Jackson's 'Liberian Girl' on Bad in ‘87.

Swinging London

On the other side of the Atlantic, South African jazz exiles made an equally huge impact on the London scene. What the Jazz Epistles were to New York, the London exile scene was primarily influenced by the Blue Notes. As a “mixed race” sestet, they were especially prone to police harassment in South Africa, soon realizing that the only way they could play freely was by escaping. After an appearance at the 1964 Antibes Jazz Festival in France, the group decided to stay in Europe, later taking up club residencies in Zurich and Geneva, at the famous Ronnie Scott's in London, and in Copenhagen.

The group disbanded in the late 1960s. Tenor saxophonist Nikele Moyake returned to South Africa as early as 1965 and died soon after. Trumpeter Mongezi Feza stayed put in Copenhagen, playing until his death in 1975. The band’s rhythm section, Johnny Dyani and Louis Moholo, toured South America with American saxophonist Steve Lacy. Dyani later moved to Denmark, where he died in 1986. Pianist Chris McGregor established the successful Brotherhood of Breath and lived in France until his death in 1990. Saxman Dudu Pukwana, Feza and Moholo played in London-based Afro-rock band Assagai. Pukwana died in England a month after McGregor. The three were also part of the similarly styled jazz-rock-kwela outift Spear with Julian Bahula, who had come to London in 1973 and became a popular musician, bandleader and promoter.

The Blue Notes are now considered one of the great free jazz bands of their era. For South Africans, they were the nexus of the London scene, around which floated a host of other jazz exiles like guitarist Lucky Ranku, singer Pinise Saul and trumpeter Claude Deppa, and others too numerous to mention here but each influential in their own way.

Bheki Mseleku

Durban-born pianist Bheki Mseleku left South Africa in the late 1970s for London, when in his early 20s. After extensive touring around Europe and the UK, his debut performance at Ronnie Scott's in 1987 catapulted him from the sidelines, eventually leading to the release of his star-studded debut album Celebration (1991), nominated for British Mercury Music Prize for Album of the Year. Over the years, he also spent time in Botswana, Sweden, and the USA, also touring the Far East and India.

Bheki’s fame was late in coming. After years of hard work, his ship was only beginning to come in by the time Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990 and it became clear that apartheid was in its death throes.

Coming home

The majority of these musicians returned home, many for the first time in three decades. Some were personally invited by Madiba when he visited Europe soon after his release. Ibrahim returned with Sathima Bea Benjamin, as did Hugh Masekela, Hotep Galeta, Jonas Gwangwa, Letta Mbulu and Caiphus Semenya. Together they performed at the landmark Unity '91 Festival, the first time they had shared a stage with their fellow musicians on home soil for 30 years. Having been away for so many years, many said they struggled to adapt at first. Many left behind adult children who had since learned to call another country home.

Bheki Mseleku returned in 1994 but his homecoming proved a bittersweet affair. At home, he did not receive the same recognition he did in Europe or the US. He struggled to get a decent gig, reportedly squandering his earnings and losing in a burglary his cherished sax-mouthpiece that once belonged to John Coltrane. With his health deteriorating due to severe diabetes, he decided to move back to England in 2006 in search of a steady income that he could not find in his SA. Disillusioned and no doubt angry, he passed away on 9 September 2008 at the age of 53. He was due to visit South Africa for a series of concerts, including a gig at the Bassline.

Mseleku’s death recalls that of Kippie Moeketsi, hailed as the father of modern South African jazz, who chose to remain in SA after touring with King Kong, but died penniless, alcoholic and dejected in 1983.

In a 2002 interview, Abdullah Ibrahim told BBC News: "What apartheid did was to break the cultural continuity. Many musicians died in exile. In our experience it was as though a generation had been totally wiped out. There was a time when the culture was just annihilated…It is actually up to us to make people aware of this legacy."

Makeba passed away in Italy in 2008. Galeta died in Johannesburg in 2010. Benjamin died in Cape Town in 2013.

As another Heritage Day passes by, let’s take time to remember Kippie Moeketsi and Bheki Mseleku, and all the others who died either in exile without a home, or at home, without freedom, those still alive who found success overseas while staying true to their roots, not to mention the others who played their parts – people like Father Trevor Huddleston, Harry Belafonte and Duke Ellington. Jazz fan or not, let’s never forget the contribution these people have made to our country.

Originally published in the now-defunct Levi’s Original Music Magazine on 15 October 2008.

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments