Germany's Polyversal Souls 'bring' Afrobeat to Lagos

On Tuesday 17 May, Lagos got a taste of just how much Afrobeat has gone beyond Nigeria. The venue was Freedom Park on Lagos Island and the band Polyversal Souls, from Germany, was billed to perform at 8pm.

Guy One performing as Florence Adoono looks on. Photo: Jere Ikongio

Guy One performing as Florence Adoono looks on. Photo: Jere Ikongio Band members of Polyversal Souls. Photo: Jere Ikongio

Band members of Polyversal Souls. Photo: Jere Ikongio Max Weissenfeldt of Polyversal Souls. Photo: Jere Ikongio

Max Weissenfeldt of Polyversal Souls. Photo: Jere Ikongio Polyversal Souls

Polyversal Souls

As with many a show in Lagos, the concert started off late. Only this time the fault wasn't traffic but, as it seemed to this observer, some technical fault.

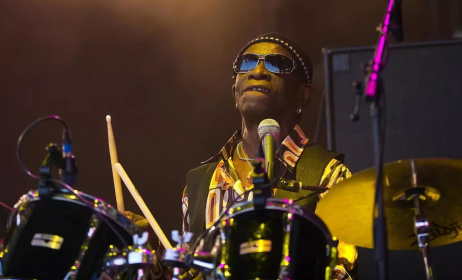

About an hour later, director of the Goethe-Institut Nigeria, Marc-Andre Schmachtel, introduced Max Weissenfeldt, leader of Polyversal Souls, who opened the show by speaking about the experience of a workshop his band held with students of the Music Society of Nigeria.

"Everybody enjoyed it,” he said. “We've decided to include the piece we worked on, ‘Invisible Joy’, which was the title of our last album. Please enjoy Polyversal Souls featuring the Invisible Joy Orchestra."

The song ‘Invisible Joy’ had the title as chorus. From what was audible of the lyrics, music appeared to be the titular joy. As the song ended, the group of singers moved through the mass of drinkers and watchers. A break in the music ensued, filled minutes later with horns, flute, and piano played by a highly demonstrative pianist.

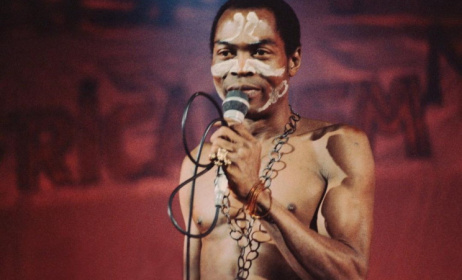

Weissenfeldt returned. "Usually we are seven guys from Germany,” he said. "Today we have two Ghanaians: Florence Adooni and Guy One. Guy One is a Ghana Music Award winner for best traditional music, so you have a real superstar here." Polite applause followed his words as the band began tuning their instruments.

In the audience, Schmachtel looked intently, some looked at the stage, others looked at their beers. The Ghanaian award winner was now lead vocalist. In his hands was a string instrument. "Isn't that the instrument used by Dan Maraya Jos?" asked a guest, referring to the popular musician from northern Nigeria. He was right: Dan Maraya played the kontigi and Guy One uses the kologo; same instrument, different names. Another string instrument, the seperewa, is also used in Ghanaian traditional music.

Adooni accompanied Guy One, singing softly with him and moving delicately. Together they produced pleasant music in the Frafra language of northern Ghana. "They are on tour sponsored by the Goethe-Institut,” said Schmachtel later in response to how the band came to Lagos. “They have been to Accra, where they have a long history because they already did an album with Guy One. And Max is very famous in Germany as he has been experimenting with African sounds."

Onstage Max on drums did a solo, his band members turned to spectators. "I like him as a drummer, " Schmachtel said. “His band was selected for the West African tour because it already had a connection to West Africa through Guy One.”

“Do you know Fela?” Max asked, a question that in Nigeria to a certain audience might result to tantrums luckily drew only a subdued response from the audience. "Do you know how to dance?” he continued. “Your chance."

Then he played an Afrobeat tune. Guy One penetrated the wall of afrobeat sound with his kologo, and the result was an excellent concoction of west African music. A Ghanaian playing a Nigerian genre was perhaps partial paypack for the perception that Nigerian highlife music owes debt to Ghana. A pattern of borrowing that has been repeated in contemporary times with the adoption of Ghana's azonto music and dance by pop acts Wizkid, Olamide and others.

"I see you don't like to dance," Max said. "It's very hot." More speech to warrant tantrum throwing. The Nigerian audience, unknown to Mr Weissenfeldt, is as amorphous as it is erratic. It chooses to dance by venue and by class—dancing being quite different from appreciation. Not all good music compels Lagos to dance. With Polyversal Souls, the audience was more curious than dance-y. In spite of the several editions of the international Fela-celebratory concert Felabration, with its multi-racial bands playing at this very venue, Afrobeat by a white band remains too infrequent to be taken as normal. First, the audience processes the unfamiliarity; then a decision regarding dance is taken.

Adooni anchored a song and received applause. She sang another, a buoyant tune. Some members of the audience began to sway in time to her singing and the backing band’s rhythm.

The show was coming to an end, announced Max. The next song will be the last one. The audience objected. And then Max reminded the audience that everything must have an end. "It's not philosophy," he said, “It is fact. I will have an end. You will have an end. This song will have an end. But don't worry. It's a long song. It is two hours!" His audience laughed and the band played a song that was closer to 10 minutes than two hours. This last song was faster, the strings of the kologo dominant. At least one person was dancing. Another was bopping her head. Schmachtel was doing something with his feet. "One more," the audience chanted when the song ended.

"Okay," Max said, before launching into a story about meeting Guy One three years ago. "I saw his name on a record,” he said. “Guy One. So easy to remember.” Then he travelled to Accra and thought to find this man whose music had entertained him so. He asked the first guy he met as he came off a bus, "Guy One, yes! I know him. I take you!" was the response. They have maintained a relationship ever since.

The last song was a mellow one, made of mostly instrumentals and the late entry of vocals. And then the concert was over. Applause rang through Freedom Park.

"It was great," said Polyversal Souls saxophonist Bastian Duncker post-applause, speaking about the band's time in Nigeria. "We were surprised things were different from Ghana. Nigeria is closer to Europe and I found it easier to connect. I really liked the kids from MUSON. They were really nice and enthusiastic to learn.”

The band flew from Lagos to Abidjan, then Cotonou, then Lomé. They return to Nigeria to play the country's capital, Abuja. “Then we fly back to Germany,” Duncker added. “We have a couple of concerts to play there."

Adooni agreed with Duncker's assessment, saying she likes the city. "We'll come back to Abuja,” she said in a voice almost singsong.

It wasn’t all great, however. As Max said later, there were small issues. "It wasn't major mistakes,” he said, and then he added, referring to what sounded like a commonplace irritation: “If a European is playing an African rhythm, never disturb him because he loses it!"

Commentaires

s'identifier or register to post comments